A couple of insightful responses to Joe’s earlier post:

Clayton Chrusch:

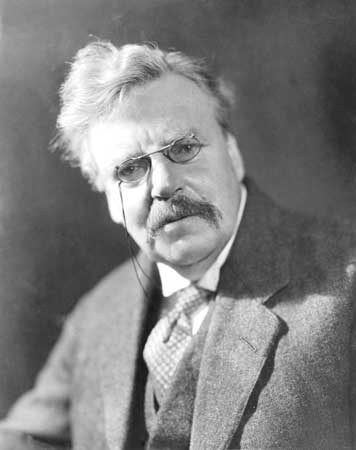

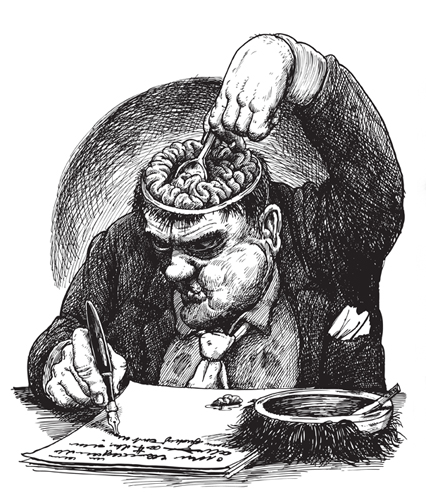

I understand what you are saying. I think the difference is that relating literature to economics or politics or power relations between the sexes, is setting up a determinism with the implication that literature has no empirical structure that is proper to itself; in other words, it empties literature of literary content.

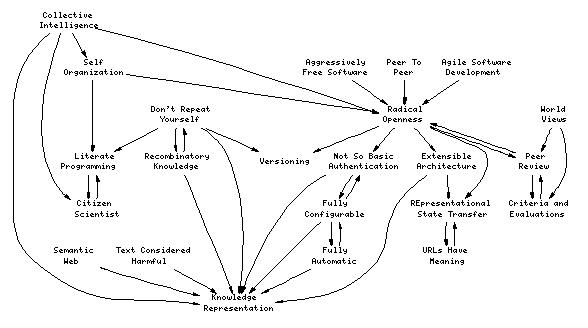

But bringing logic or even math to the table is a different matter, because these are tools that can be used to build a properly literary structure, they are not the structure itself, they do not usurp the content of literature. Frye liked to make analogies between the study of literature and other disciplines, and if you consider other disciplines, you see that the use of mathematics or logic does not work to subordinate them to something outside themselves.

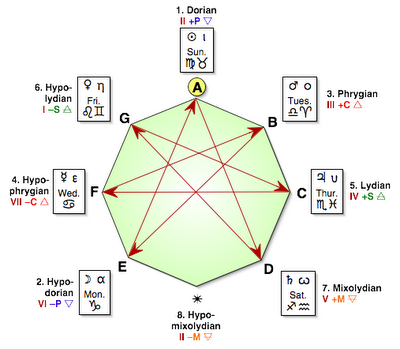

Frye liked to use diagrams. That did not subordinate literature to geometry or graph theory.

I’m not insisting that everyone think as I do, but I do believe that if people with a logical temperament could find a place in literary studies, they could do a lot to build an objective(ish) “science” of literary convention which would establish the properly literary structure of literature.

Jan Gorak:

It does seem a shame that no one seems to ask why anyone would want to cast a work in literary form any more – something that The Educated Imagination itself addressed so well I always thought. I also think Frye – and many of his contemporaries – were much better at seeing and talking about the various constructions human beings deploy and the motives for deploying them. Contemporary critics seem to have gone back to the dark ages on questions like this, so that you often wonder whether they would even recognize an allegory if one bit them! It would also seem relevant to say that although Frye thought that he inhabited the same imaginative universe as Blake, Coleridge etc, most contemporary theorists are convinced that anything before 1968 let’s say is completely out of their field of vision, so you get bizarre frames of reference brought to bear in the name of “redefining the Victorian idea” or whatever. Sho’ is a mysterious discipline these days. Good to be in touch!