A number of posts and comments over the last few days have touched on the matter of Frye and paradox. Yesterday I cited Wilde’s aphorism that “The way of paradoxes is the way of truth.” Matthew Griffin responds:

Wilde is cribbing, and making more pronounced, a point Coleridge makes in the Biographia Literaria – itself a neat book for Frygians – that any meaningful truth can only be expressed in paradox.

So Coleridge — whose Biographia Literaria is one of Frye’s critical touchstones — is now in play. Is “paradox” an essential aspect of Frye’s criticism? If so, where is it articulated?

I think paradox is for Frye a primal creative condition of language as laid out in essay two of Anatomy, “Ethical Criticism: Theory of Symbols.”

Frye’s theory of symbols presents an expanding dialectic of metaphorical meaning: the literal (symbol as motif), the descriptive (symbol as sign), the formal (symbol as image), the mythical (symbol as archetype), and the anagogic (symbol as monad). The only one of these I will deal with in any detail here is “literal” metaphor, effectively the singularity or big bang of verbal phenomenon from which Frye’s “verbal universe” expands.

Frye points out in this essay what he repeats elsewhere; that language has both “centrifugal” or outwardly directed, and “centripetal” or inwardly directed reference. When reference is primarily outwardly directed we have a “sign” whose function is to point to “the thing represented or symbolized by it” (AC 73). Hence, “cat”. However, when reference is primarily inwardly directed we have a “motif” whose function is to “connect” elements of verbal phenomenon. Hence, “c – a – t”: that is, the discrete constituents, whether written or uttered, that make up the centrifugally referenced sign “cat.” Frye, in a famous reversal, calls the centripetal direction of meaning “literal” metaphor, not because it ensures accurate and reliable descriptive reference (as the word is most commonly used), but because it refers to artfully ambiguous “units of verbal structure” — or that which is proper to the “letter” — whose primary internal relation is a necessary condition for meaning of any kind.

As Frye goes on to observe, these “two modes of understanding take place simultaneously in all reading.” However, a distinction can still be made between verbal structures whose final direction of meaning is either inward or outward. In “descriptive or assertive writing,” reassuringly enough, the direction of meaning is centrifugal. In all literary verbal structures, on the other hand, the direction is centripetal:

In literature the standards of outward meaning are secondary, for literary works do not pretend to describe or assert, and hence are not true, not false, and yet not tautological either, or at least not in the sense in which such a statement is “the good is better than bad” is tautological. Literary meaning may best be described, perhaps, as hypothetical, and a hypothetical or assumed relation to the external world is part of what is usually meant by the word “imaginative.” This word is to be distinguished from “imaginary,” which usually refers to an assertive verbal structure that fails to make good on its assertions. In literature, questions of fact or truth are subordinated to the primary literary aim of producing a structure of words for its own sake, and the sign-values of symbols are subordinated to their importance as a structure of interconnected motifs. (AC 74)

The significance of this imaginative, hypothetical, and centripetally “literal” meaning to a properly literary criticism is crucial:

Now as a poem is literally a poem, it belongs, in its literal context, to the class of things called poems, which in their turn form part of the larger class known as works of art. The poem from this point of view presents a flow of sounds approximating music on one side, and an integrated pattern of imagery approximating the pictorial on the other. Literally, then, a poem’s narrative is its rhythm or movement of words… Similarly, a poem’s meaning is literally its pattern or its integrity as a verbal structure. Its words cannot be separated and attached to sign-values: all possible sign-values of a word are absorbed into a complexity of verbal relationships. (AC 78)

The dialectical direction of what Frye calls a “complexity of verbal relationships” is to a large extent what the remainder of this essay addresses as he works through literal meaning to the anagogic, where the apocalyptic turn of the imagination perceives at last that the whole of nature may be regarded as a human artifact recreated by specifically human concerns. But here, at the very genesis of meaning, is a centripetal verbal power to assert that which is not, but which nevertheless possesses dialectically expanding significance. Metaphor, as Frye regularly reminds us, expresses both what is and is not. What it expresses, however, is real, inasmuch as it articulates a human condition — including our capacity for language — that has the (anagogic) potential to become fully aware of itself as such.

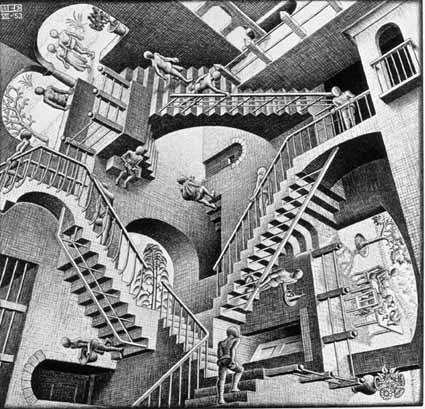

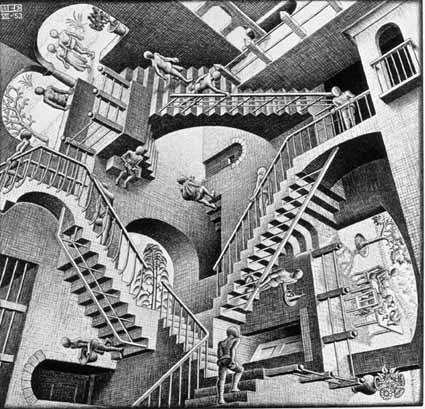

The famous illustration above is M.C. Escher’s “Relativity,” which nicely captures the “what is” / “what is not” capability of the human imagination where even an “absence” is still a “presence” because it can be expressed. The concept of “relativity” is as distinct from “relativism” as the “imaginative” is from the “imaginary.” “Relativism” seems to dominate current literary criticism which somehow finds its criteria (in ideological constructions such as gender, class, race, and so on) outside of literature as though literature were primarily centrifugal in reference. “Relativity,” on the other hand, requires a constant: in Einstein’s case, that constant accounts for bodies in motion relative to one another. And, it seems, the same is true for Frye as well; the constant in this case being those primary human concerns which are everywhere evident in literature and provide the impetus for us to communicate at all. Concern is the gestalt of verbal expression; and literature — in its simultaneous acknowledgement of what is and is not as an integral part of its saying — confronts the inadequacies of the world we inhabit with a world we are trying to create through the imaginative expression of our universally shared but individually possessed concerns.