Ron Krumpos recently drew our attention in a comment to Stephen Prothero’s new book, God Is Not One. Prothero was on The Colbert Report last night. The interview can be seen in Canada here. In the rest of the world, here.

Category Archives: Religion

Frye on Bardo

Cross-posted in the Robert D. Denham Library

In Mahayana Buddhism, bardo, a concept that dates back to the second century, is the in-between state, the period that connects the death of individuals with their following rebirth. The word literally means “between” (bar) “two” (do). The Bardo Thödol, or “Liberation through Hearing in the In-Between State,” distinguishes six bardos, the first three having to do with the suspended states of birth, dream, and meditation and the last three with the forty-nine-day process of death and rebirth. In The Tibetan Book of the Dead, which is the principal source for Frye’s speculations on bardo, a priest reads the book into the ear of the dead person. The focus is on the second three in-between states or periods: the bardo of the moment of death, when a dazzling white light manifests itself; the bardo of supreme reality, in which five colorful lights appear in the form of mandalas; and the bardo of becoming, characterized by less-brilliant light. The first of these, Chikhai bardo, is the period of ego loss; the second, Chonyid bardo, is the period of hallucinations; and the third, Sidpa bardo, is the period of reentry.

In Frye’s Bible lectures he mentions the bardo in connection with the issue of whether one can be released from various projections and repressions and so escape from the wheel of reincarnation, or at least have the possibility of escaping next time around if one will only be attentive. There, he said,

The word “apocalypse,” the name of the last book of the Bible, is the Greek word for revelation. That is why the book is called Revelation in English translation, and what John at Patmos sees in the book is a panorama of certain things in human experience taking on different forms. There is an analogy which seems to be a fairly useful one in the Oriental scripture known as The Tibetan Book of the Dead. When a man is dying, a priest comes to his house, and when the man dies, the priest starts reading the Book of the Dead into his ear, because the corpse is assumed to be able to hear the reading and to be guided by what is said. The priest explains to the corpse that he is going to have a progression of visions, first of peaceful deities and then of wrathful deities, and that he is to realize that these are simply his own repressed thoughts and images coming to the surface because they have been released by death; and that if he could only understand that they are coming out of his mind, he could be delivered from their power, because it is really his own power. lt is also assumed that practically every corpse to whom this book is read will be too stupid to understand what’s going on, and will go on from one blunder to another until finally he wakes up in the world again: because the assumption behind it is one of reincarnation. [CW 13, 587–88]

Otherwise, in his published writing Frye refers to bardo infrequently––once in The Great Code, once in A Study of English Romanticism, once in “The Journey as Metaphor,” and twice in “Yeats and the Language of Symbolism.” In his notebooks and diaries, however, the word “bardo” appears more than one hundred times, and Frye’s own copy of The Tibetan Book of the Dead contains some 240 annotations. In Northrop Frye: Religious Visionary and Architect of the Spiritual World I point out that Frye almost always uses “bardo” in a telic sense: it represents a stage toward the end of the quest, and it is related to such ideas as epiphany, resurrection, recognition, and apocalypse––ideas that are omnipresent in Frye’s writings. But his understanding of bardo warrants further study.

The following entries represent, I think, all of the places in Frye’s “unpublished” writing (now a part of the Collected Works), where the word “bardo” appears. The “published” references are at the end. The annotations have been omitted. All material within square brackets is an editorial addition.

John Calvin

On this date John Calvin died (1509 – 1564).

Here’s Frye in a student essay, “The Importance of Calvin for Philosophy”:

It is obvious that if we look at Calvin we can see in his view of God a Cartesian feeling for order and permanence, and that if we look at his view of man we see that for him human activity springs from sources deeper than the human will. The immense energy and uncompromising heroism of Calvinism, its tendency to consolidate in theocratic dictatorships, sufficiently refute the theory that according to it our relation with God should be one of helpless quietism. As a social force, Calvinism identified itself more explicitly with the bourgeois than with the royal side of the alliance of prince and middle class, in opposition to the Erastians, but as a doctrine both factors are present. But they are present in antithesis, not synthesis; God and man have too wide a gap between them. Just as Aquinas had extended the feudal society of his day into heaven and established a hierarchy of angels leading up to God, so in Luther we find an absolute monarch protecting the interests of a democratic body saved through their faith in and obedience to him. There is something of this in Calvin, but on the whole his scheme disregards the state and the organization of human society, resting on an Augustinian dualism between a city of God, or body of elect, and an excluded world.

As our civilization becomes more mature, it is bound to expand and take in more of its cultural heritage. A greater eclecticism will no doubt do much to rehabilitate Calvin, but the positive contribution of the thought between Calvin’s time and ours cannot be ignored; nothing less than the full consciousness of the unity of our tradition will be satisfactory for us. And it seems that the time-philosophy of the last century has a real value in reinforcing Calvin’s doctrine. Now that evolution has penetrated into our intellectual make-up, we are beginning to sense the working out of a purpose in the organic world, so that the Manichean dualism of a static principle of good existing beside an unregenerate nature, which came into Christian thought with Augustine, is no longer necessary for us. Of course, as we have said, the purely evolutionary doctrine, that the only truly elect are posterity, and that the ideal is actualized at the end of a historical progression, is full of contradictions and is, when pressed to its logical conclusion, unthinkably repulsive. But nonetheless we have inherited a feeling which expressed in Christian terminology might be said to be a perception of the creative, developing, redeeming power of the Holy Spirit in the affairs of men, conserving the good, progressing toward the better. To assume that this exhausts God’s activity is to assume God an imperfect force striving to self-realization, such as we find in the creative evolution religions of such thinkers as Bernard Shaw. The weakness of such an attitude is that it recognizes no evolutionary lift in human history; it depends ultimately on geology for its religious dogmas and in most cases turns to the idea of the development of a “superman” which, expressed again in Christian terms, amounts practically for a call for an Incarnation, an identification of the evolutionary principle with an historical event. Nor has it a firm enough grasp of the permanence, pre-existence, and immutability of the phenomenal world, the world as an object of understanding, which the immediate successors of Calvin perhaps overemphasized. (CW 3, 414-15)

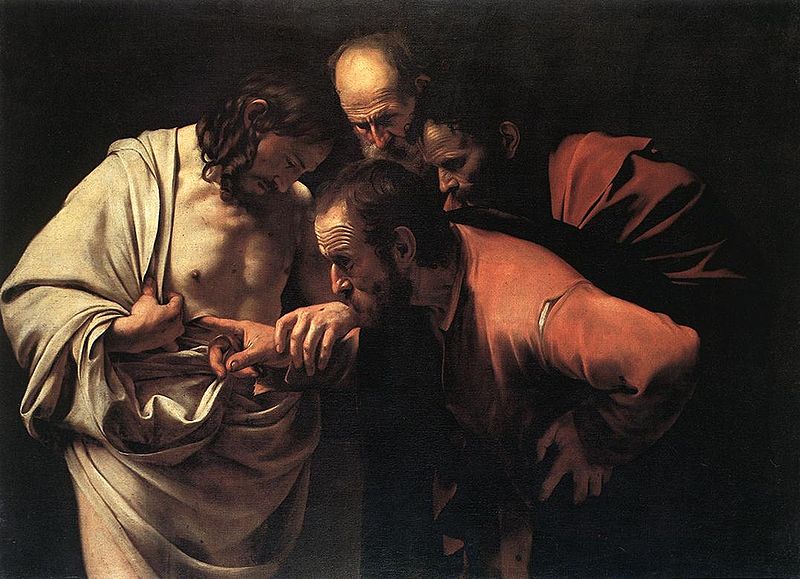

Easter

Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1601

From the Late Notebooks:

When Jesus says “I am the way” [John 14:6] time stops. There is no journey through unknown country: all the disciples have to do is walk through the open door (another “I am” metaphor [John 10:9]) of the body in front of them). That is, I think, impossible before the Resurrection. Perhaps everything that happens in the gospels is not an event but a ticket to a post-Resurrection performance. Except that the spiritual reality is not so much future as an expansion of the imaginative possibilities of the present. The myth confronts: it doesn’t prophesy in the sense of foretelling. (CW, 5, 159)

Jesus is not “a” historical figure: he’s dropped into history as an egg is into boiling water, as I said [par. 301], and essentially “the” historical Jesus is the crucified Jesus. One can understand why the Gnostics tried to insist that the crucifixion was an illusion, but nobody can buy that now. The pre-Easter Jesus answers the question: ‘Can a revolt against Roman power succeed?”

The answer is no, and the pre-Easter Jesus sums up the history of Israel, which is a history of “historical” failure. (CW, 5, 170)

The Resurrection, then, is the marriage of a soul & body which forms the spiritual body. The body part of this marriage is female: the empty tomb is recognized solely by women, except perhaps for that fool who stuck Peter into John’s account [20:1-10]. (Perhaps the “and Peter” of Mark [16:7] was stuck in too.) The fact that Jesus took on flesh in the Virgin’s womb has certainly been dinned into Christian ears often enough; but the fact that he took on flesh in the womb of the tomb at the Resurrection, and that there’s a female principle incorporated in the spiritual body, seems to have been strangled. The real tomb of Christ was the male-guarded church. (CW, 5, 327)

The historical Jesus is a concealed though essential element in the Gospels: if the Gospels’ writers had simply made up the Jesus story they would still be superb works of literature, but of course they wouldn’t be gospels. The myth is what they literally are, though: they don’t present Jesus historically. Historically, Jesus is a man until the Resurrection, when he becomes an element in everyone, implying that no one can be “saved” (meaning the indefinite persistence of something like an ego in something like a time and space) outside or before Jesus. Presented as a myth in the eternal present, this doctrine takes on a more charitable appearance. The Word and Spirit in man then coincide into something that has its being in God (as God has his being in it) to such an extent that the question of belief in “a” God doesn’t arise. (CW, 6, 671)

From CBC radio “Rewind”, various Easter broadcasts dating back to the 1940s, including Frye in 1973 on Easter myths and symbols (beginning at the 24 minute mark).

Nicholas Graham: Lonergan and Frye

Bernard Lonergan

Responding to Joe Adamson

Perhaps, a little later, Joe, I’ll be able to offer a more adequate response to your posting which I really enjoyed. It was lively, direct and disturbing to some of my friends who told me to stop sending them such diatribes. But seriously, it touched on points that I worry about myself, especially the subjection of human concerns to metaphysical transcendental norms which I take to mean Nobodaddy in Blake and the priest and king in Joyce’s Ulysses.

For the moment, here are a few points. As you well know, Frye was a double major in Philosophy and English and initially I searched his writings for evidence that he was philosophically an idealist or a naive realist. I was amazed to find that he was neither. He was like Lonergan a critical realist: reality is reached in the act of judgment, however probable it may be. After reading the first chapter of Fearful Symmetry, The Case Against Locke, I was committed to making a serious study of Frye.

In the late 60s, Lonergan was introduced to the syllabus of the Jesuit seminary, Dublin, Ireland. It is hard to describe what a breath of fresh air it was compared to the old Latin texts which were used up till then. We initially wondered what good could come out of Canada, especially in the areas of philosophy and theology, which the Germans had taken over.

What we found in Lonergan’s Insight was an alternative to scholasticism with its metaphysics and epistemology. It was an alternative to faculty psychology with its focus on the attributes of the soul:memory, intelligence, and will. Instead we were invited to examine our conscious operations: “what” questions and “is” questions as the prior conditions for having an insight.

Our basic texts turned out to be detective novels rather than Aquinas. In a detective novel all the clues are given, yet we fail to spot the criminal, until we have the required insight. Lonergan had studied the act of insight in Plato and Aristotle and Aquinas who did not thematize the act, as Lonergan does in his INSIGHT, but they knew that it was insight that put life into their otherwise dry works.

Lonergan’s then worked out a method in theology based on his book Insight which examines modern science, mathematics, common sense, etc. The point of working out a Method in Theology was to enable theologians to police themselves by peer approval, instead of of being condemned or silenced by some bishop in Rome.

Lonergan’s point of contact with Frye is that they are both Canadian: Sherbrook for Frye and Buckingham Quebec for Lonergan. They both have an encyclopaedic approach to their work. They both work with a four leveled universe, a squared circle diagram, as Joe mentions in his book, A Visionary Life. Lonergan assigns a transcendental precept or norm to each conscious level which we reach through acts of self-transcendence: Be Attentive, Be Intelligent, Be Reasonable, Be Responsible. But these are not some metaphysical entities, some attributes of the soul, these are are personal acts which can be verified in one’s own consciousness. And this verification is what the exercises in Insight are designed to bring about.

Similarly, my reading of Frye’s Secular Scripture brought me to proclaim Frye as the Einstein of the verbal universe. There Frye presents us with four levels of time and space. There is demonic time (Macbeth’s tomorrow, and tomorrow) and there is demonic space (Hell). There is ordinary time (clocks) and ordinary space (mirrors). There is cultural time (music) and there is cultural space (painting). There is anagogic time (Now, the real present) and there is anagogic space (Here, the real presence).

So, to conclude for the moment, Lonergan and Frye share in Blake’s fourfold vision, however much it remains only implicit in the work of Lonergan.

Michael Dolzani: Spiritual Otherness (2)

Von Carolsfeld, Samson Destroys the Temple, 1880

Responding to Matthew Griffin and Clayton Chrusch, regarding my earlier post.

Matthew, I am moved by the warmth and generosity of your response. I’m very glad what I wrote was useful to you, all the more because there is a reciprocity: your response was what chiefly inspired a follow-up posting of mine that I’ll be sending along as soon as I’m sure it’s entirely coherent. The Hebrews passage is indeed a key, and I thank you for reminding me of it. Epiphany is a perfect time to be discussing these things–I hadn’t even thought about that!

Second, to Clayton Chrusch: Wow. I admire the marriage of articulate intellect and emotional intensity in this response. Literary criticism could use more of this directness. You raise issues so immense that I know I haven’t thought through them completely yet, but you deserve at least something of an immediate response. Concerning God, yes, as Jesus he is an object, a historical personage–and therefore bound up with all the ambiguities of our relationship to objects, starting with the fact that there is no historical evidence that he even existed. The quest for the historical Jesus leaves us more distanced from God than ever. God could also be considered as a subject, but not as what we usually mean by a subject, namely, the ego of the natural man. Jung’s Self/ego distinction is helpful here, and the Jungian Self is in fact a God-image. If God is a person, it is not the same sense in which I am a person. For example, he is not limited by time and space, those conditions which define ego-consciousness. When Paul says, “I, yet not I, but Christ in me,” he is speaking of the person of Christ as dwelling within him, an interpenetration that the ego or natural man is not capable of. I’m sure you know all this; I’m just struggling to clarify my vocabulary.

I absolutely agree with you that “real” and “true” are words that may be applied to the imagination; otherwise, the imagination’s products are just beautiful illusions, and that gets us nowhere. I was just trying to make the distinction that “real” and “true” here must mean something other than “objectively factual.” A scientist or historian means something else by these terms. That’s why the reality and truth of the spiritual world cannot be proved by scientific or historical methods.

As for suffering, I don’t think you misspoke–in fact, that was probably the part of your response that I admired the most. I see why you qualify the response, though: yes, there are things more important than avoiding pain. Though I’m sure you’d agree that we have to be careful to state this precisely, because what we’re really talking about here is martyrdom. For the Tibetan monks, or the early Christian martyrs, this meant accepting their own suffering for the sake of something more important. But when I teach Milton’s Samson Agonistes, I ask students the troubling question: what makes Samson different from a suicide bomber? Samson too experiences “a renovation of the will so complete and so secure that it doesn’t matter any longer what place” he is in (marvelous passage, by the way). But he also finds acceptable the suffering of the Philistines who will die along with him when he pulls down the Temple, just as the suicide bombers felt when they brought down our Temple, the World Trade Center. Anyway, thank you for a searching and stimulating response.

Griffin and Chrusch: Responding to Michael Dolzani

Bosch’s Epiphany, 1495

Michael Dolzani’s first post has drawn a couple of thoughtful responses:

Matthew Griffin:

Thanks so much for this piece. It’s proven quite helpful to me, as I try to come up with some coherent thoughts for a pair of Epiphany sermons.

Epiphany is one of the principal feasts of the Church year, and celebrates the greater spread of God’s saving work beyond just the Israelites. It’s the time of year when we read the account in the gospel of Matthew of the magi coming to see the child, led by a star–and I think that one could argue that such is the quintessential example of natural religion (and then absorbed into Christianity). After all, the magi follow a star and bring tribute, ill-understanding (in the gospel writer’s eyes, at any rate) the full import of who they were meeting.

Where I would want to offer nuance to your argument is around the assertion that “the imgaination does not ‘believe in God’: belief is concerned with the evidence for or against objects, and God is not an object.” I think my quibble stems from a passage of scripture close to Frye’s heart–”Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the conviction of things unseen” (Hebrews 11.1). In fact, it was a passage that kept cropping up in papers given at the Frye & the Word conference a few years back, and it’s key to my own reading of Frye: he’s sure that faith isn’t, as he quotes “believing what you know ain’t so”–but is something other than factual, other than straight subject/object dichotomy. It’s how Frye does this that makes Words with Power such an important book in my life, and I thank you for reminding me of that as I try to think about what it means to help others re-read a myth that reveals something of how God is.

Clayton Chrusch:

The passage that Matthew identifies is the same one that I think could use some clarification. God (the Father) may not be an object, but he is, according to the view I am defending anyway, a subject, and subjects (like the human mind, for example) are still facts, and their existence can be treated (more or less) in the same way the existence of objects can be treated. According to the Christian view, God, in the person of Jesus, is actually an object, in the sense of a physical entity. But perhaps you are not contrasting objects with subjects but objects with persons. Persons, though, are also facts, and we can believe in them both in the sense of acknowledging their existence and also in the sense of trusting them.

I certainly understand Blake’s rebelliousness and share his disgust with the church which contents itself with being at best a little less bad than institutions of a similar size, wealth, and power. But I see a distinction between the church and the teachings it espouses, the teachings, in fact, that it usually betrays. And I also see a distinction between the teachings of the church, in all their inadequacy and perversion, and the truth of which they are a distortion.

So I don’t see imagination and fact as incompatible. An imaginative scientist is very good at coming up with theories that articulate and explain facts. An imaginative Christian is very good at envisioning what it means to be a God whose only motive is love and also what it means to be a child of such a God. But a vision may be a vision of what is real. The imagination shows us not only what is not true, but also what is true.

I think I misspoke in my original comment by suggesting that the hope of Christians is the end of suffering. The end of suffering is only a secondary Christian hope, but the primary one is equally factual. Suffering is bearable, but what I cannot bear, what makes me want to pluck out my own eyes or throw myself off a cliff is being bad–hurting other people or behaving dishonestly. If I hate torture, it is not because it is painful but because it reaches down into a person’s will and takes possession of it for evil purposes. If I really knew that I could be good and remain good, I would not be afraid of any amount of pain. This is not something I am making up as an ideal, but something that is a part of real life to Tibetan monks, for example, being tortured in Chinese prisons.

And so I don’t see salvation as admittance into a very pleasant place, but as a renovation of the will so complete and so secure that it doesn’t matter any longer what place we are in.

Frye and the Supernatural

I’ve been mulling over Clayton’s comment about Frye’s antisupernatruralism. There are close to a hundred places in Frye’s writings where he uses the word “supernatural,” but I don’t get the sense from these references that he’s antisupernatural. Most often Frye’s use of “supernatural” does not point to some transcendent religious realm or being. For him, the supernatural is what is fantastic (ghosts, vampires, omens, portents, oracles, magic, witchcraft, and the like) or above nature––as in the heroes of myth in the Anatomy: superior to other people (superhuman) and to their environment (supernatural). The supernatural would include the “children of nature” (“the helpful fairy, the grateful dead man, the wonderful servant who has just the abilities the hero needs in a crisis,” Anatomy 196–7) that we find in folk tales and romances. For Frye the supernatural is not a term that is opposed to unbelief. It’s simply the antithesis of the natural. In his essay on Emily Dickinson he writes, “the supernatural is only the natural disclosed: the charms of the heaven in the bush are superseded by the heaven in the hand.” Sometimes Frye speaks of the supernatural as phenomena that are difficult to explain. He reports on this episode with his mother:

She has always regarded her mind as something passive, worked on by external supernatural forces, and is very unwilling to think that anything might be a creation of her own mind—besides, it flatters her spiritual pride to think of herself as a kind of Armageddon. She told me that once she was working in her kitchen when a voice said to her “Don’t touch the stove!” So she jumped back from it, and something caught her and flung her against the table. Half an hour later the voice came again, “Don’t touch the stove!” She jumped back again and this time was thrown violently on the floor. When Dad came home for dinner he found her with a black eye and a bruised shin. I have read a story by Thomas Mann in which he tells of seeing a similar thing in a spiritualistic séance [the episode involving Ellen Brand toward the end of Mann’s Magic Mountain—the section entitled “Highly Questionable” in chapter 7]: that story was the basis of the priest’s remark to the ghost in my Acta Victoriana sketch: “If you are very lucky, you may get a chance to beat up a medium or two” [“The Ghost”]. Mother has also heard noises like tapping and so on, and was tickled to get hold of a copy of a Reader’s Digest in which a writer describes having gone through exactly similar experiences [Louis E. Bisch, “Am I Losing My Mind?” Reader’s Digest, 27 (November 1935), 10–14.] The best way to deal with mother is, I think, to get her books telling of similar things that have happened to other people: she’s not crazy, but might be excused for thinking she was if she didn’t realize that such things are more common than she imagines. She was delighted with my Acta story, and I’ll try to get her that Mann thing and C.E.M. Joad’s Guide to Modern Thought, which has a chapter on those phenomena. (Frye-Kemp Correspondence, 13 August 1936).

In Fearful Symmetry Frye speaks of the supernatural as the human creative power: “All works of civilization, all the improvements and modifications of the state of nature that man has made, prove that man’s creative power is literally supernatural. It is precisely because man is superior to nature that he is so miserable in a state of nature” (41). Frye’s reaction to natural religion, with its premise of the analogia entis [anology of being], is almost always negative. Both Word and Spirit, he declares in his Late Notebooks, can be used without any sense of the supernatural attached to them.

“Allah Akbar”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qmuSeyLjI5Y

If you’re following events in Iran, you know that what may soon be referred to as the Ashura Revolution is underway throughout the country and particularly in Tehran, with crowds of protesters out in the streets daily in numbers that haven’t been seen since June and July. Young people especially continue to be targeted for beatings, rape and murder by regime thugs, the basij militia. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei is now openly reviled. There is talk of a general strike, beginning as early as Monday. This illegitimate regime may finally be losing its grip. One telling sign is that the fraudulent “president” Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is nowhere to be seen and is not mentioned even in state media.

The video above features a nightly phenomenon: people at their windows or on their rooftops shouting “Allah akbar” en masse. Andrew Sullivan calls it the “cry of freedom,” and it is, as Frye would say, as primary as it is primal. Sullivan’s site is easily the best raw news source anywhere at the moment — his Iranian contacts are pouring in reports hourly, and he’s blogging around the clock on developments. If you want to know what’s happening in Iran in real time, then Sullivan’s Daily Dish is the place to go. Be warned, some of the video he posts is disturbing. As Sullivan himself has put it, this revolution may not be televised, but it will be YouTubed. Welcome to the new world of New Media. It’s why CNN is withering on the vine and newspapers are hemorrhaging readers.

The Chorus of Bethlehem Angels

Correggio's Nativity

Frye writes:

If I had been out on the hills of Bethlehem on the night of the birth of Christ, with the angels singing to the shepherds, I think that I should not have heard any angels singing. The reason why I think so is that I do not hear them now, and there is no reason to suppose that they have stopped. (The Critical Path, 114)

History tells the reader what he would have seen if he’d been present, say, at the assassination of Caesar. But what the Gospels tell us is rather something like this: if you had been present on the hills of Bethlehem in the year nothing, you might not have heard a chorus of angels. But what you would have seen and heard would have missed the whole point of what was actually going on. Thus, the antitypes of history and of prophecy as we have them in the gospel and the apocalypse give you not what you would have seen and heard, or what I would have seen and heard, but what was actually going on which we don’t have the spiritual vision to reach to. (“Kerygma,” in Northrop Frye’s Notebooks and Lectures on the Bible and Other Religious Texts, CW 13, 588)