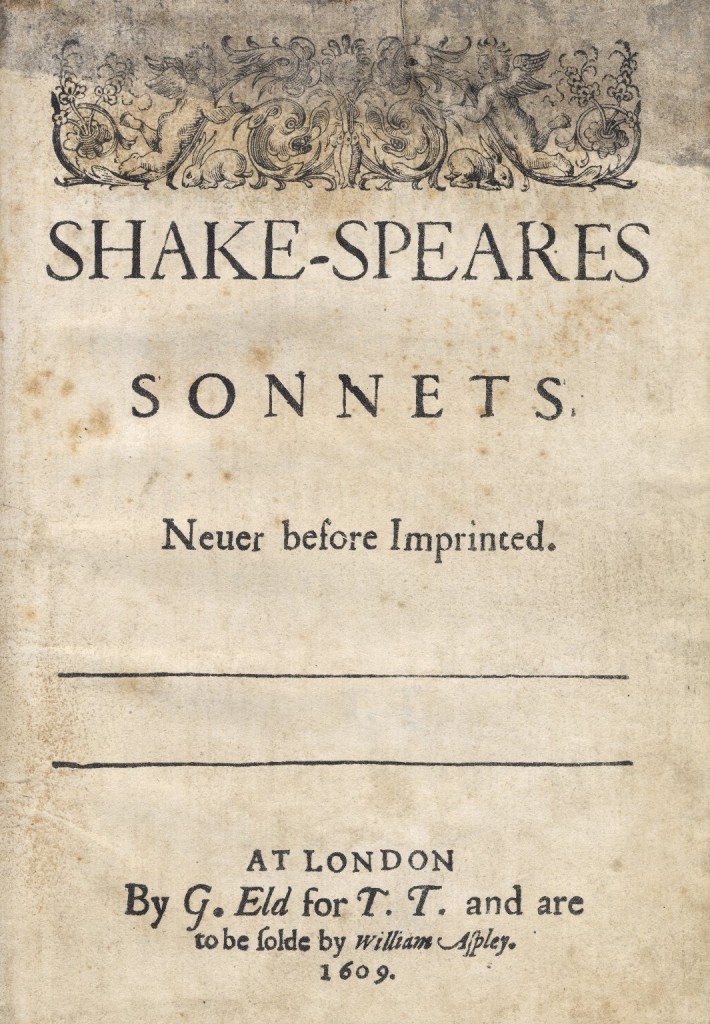

The “Cobbe portrait,” allegedly a newly-identified image of Shakespeare fully decked out in establishment conformist finery

In an earlier post, I compared Northrop Frye’s and Graham Greene’s readings of Henry James. Greene’s criticism often seems eccentric, a product of the same obsessions that drive his fiction. His discussion of Shakespeare is as distinctive as his essays on James. In 1969, Greene received the Hamburg Shakespeare Prize, endowed by an Anglophile German, and awarded to British citizens for artistic achievement. He marked the occasion with an address entitled “The Virtue of Disloyalty” which begins,

Surely if there is one supreme poet of conservatism, of what we now call the Establishment, it is Shakespeare. . . . If there is one word which chimes through Shakespeare’s early plays it is the word “peace.” In times of political trouble the Establishment always appeals to this ideal of peace. . . . Peace as a nostalgia for a lost past: peace which Shakespeare associated like a retired colonial governor with firm administration.

In what follows, two of Greene’s major obsessions, Roman Catholicism and betrayal, coalesce in a discussion which, however inadequate as Shakespeare criticism, reveals much about Greene’s view of the writer’s role in society. One should bear in mind that the speech was given during the Cold War, at a time when Russian dissident writers were much in the minds of people in the west, and that it was given to a German audience, about twenty-five years after the end of the second world war.

Greene is deliberately provocative in the sardonic manner in which he discusses the great national poet after whom the prize was named. “There are moments,” he says, “when we revolt against this bourgeois poet on his way to the house at Stratford and his coat of arms, and we sometimes tire even of the great tragedies, where the marvellous beauty of the verse takes away the sting and the last lines heal all, with right supremacy re-established by Fortinbras, Malcolm and Octavius Caesar.” Greene then continues:

Of course he is the greatest of poets, but we who live in times just as troubled as his, times full of the deaths of tyrants, a time of secret agents, assassinations and plots and torture chambers, sometimes feel ourselves more at home with the sulphurous anger of Dante, the self-disgust of Baudelaire and the blasphemies of Villon, poets who dared to reveal themselves whatever the danger, and the danger was very real.

Shakespeare does not, for Greene, belong in the company of Russians such as Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn, though, anticipating recent postcolonial critics, he detects a note of rebellious outrage in Caliban’s speech “You taught me language; and my profit on’t / Is, I know how to curse.”

Greene then goes on to contrast Shakespeare, “the great poet of the Establishment,” with the brilliant but minor poet and Jesuit martyr Robert Southwell. If only Shakespeare had shared Southwell’s disloyalty, Greene says, “we could have loved him better as a man.” The remainder of the short essay argues that the writer should be opposed to the State, acting as a devil’s advocate in the face of official efforts at scapegoating. The writer should always be counter-cultural, “a Protestant in a Catholic society, a Catholic in a Protestant one.” The writer should be ready to change sides at a moment’s notice, for “He stands for the victims, and the victims change.” This does not mean that the writer is a propagandist, but rather someone who enlarges the bounds of sympathy, “making the work of the State a degree more difficult.” Greene concludes, perhaps to the discomfort of some in his audience – apparently the lecture was received enthusiastically by the students who were present – by presenting, as his final example of the virtue of disloyalty the German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who “chose to be hanged like our English poet Southwell. He is a greater hero for the writer than Shakespeare.”

Continue reading →