I recall that in the earliest days of the blog we had a discussion about a possible course on Frye’s theory of literature and criticism and the ways in which they relate to wider culture, existential concerns, and social vision: Frye’s brand of “cultural studies” in short. I have put together an outline for a graduate course on just that subject and thought I might post it in the hope it may stir some discussion. I won’t be teaching the course until the winter terms of 2013 and I’d appreciate any helpful ideas or suggestions readers of the blog might have (a jazzier title might help catch the eye of theoretically jaded grad students). Here it is:

Northrop Frye and the Social Function of Literature

This course will explore the work of Northrop Frye’s mid to late career, after the publication of Anatomy of Criticism (1957). It was during this period that Frye’s attention turned more fully to the social function of literature and the exploration of its particular authority in society. In what ways do literature and the arts relate to social and existential concerns? What role does the study of literature have in education? What is the particular authority of literature, the humanities, and the arts and sciences in society? In what way does literature, as one of the liberal arts, exert a critical, liberalizing and even prophetic influence in a society? In what way is literature the expression of a particular historical culture, regional and national, and in what way does it have a more universal and trans-historical range of communication?

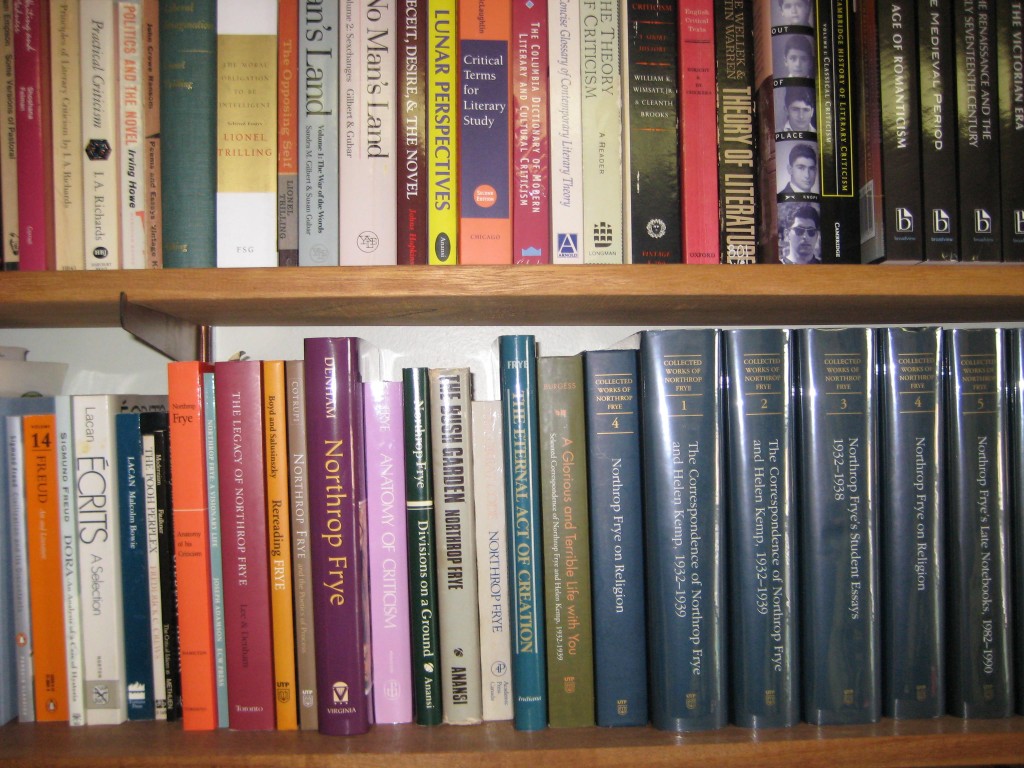

Frye remains today arguably the most important intellectual this country has produced, and yet many aspects of his thought have not yet received the engagement they deserve, largely because of the impact of Anatomy. And yet the latter is only the second of over twenty books he subsequently published, many of them with titles (or subtitles) such as “Essays on Criticism and Society,” “An Essay on the Social Context of Literary Criticism,” “On Education,” and “Essays on Canadian Culture.” His final body of work, now fully represented in the thirty volumes of The Collected Works, contains an enormous amount of writing devoted to social and cultural criticism, much of which–most notably the fascinating material in his notebooks–was never published during his lifetime.

Along with a teasing out of the most important concepts and schemes of Frye’s thought, I hope the course will provide a lively forum to engage the ways in which Frye’s ideas about literature and society challenge many of the very different conceptions that have gained ascendency over the last twenty-five years. As a way of encouraging such a discussion, I am proposing, as a test case, to set Frye’s ideas against Jean-Paul Sartre’s landmark “What is Literature?” and Other Essays (1947), an essay which in many ways anticipates the issue-oriented, ideological, and politically committed critical theory that now represents the mainstream in literary studies.

Texts: The texts listed below will be supplemented with selections from other collections of essays and books.

Northrop Frye: The Stubborn Structure: Essays on Criticism and Society (1970); The Critical Path: An Essay on the Social Context of Literary Criticism (1971); Divisions on a Ground: Essays on Canadian Culture (1982); Creation and Recreation (1980);The Double Vision (1991)

Jean-Paul Sartre: “What is Literature?” and Other Essays (1947)