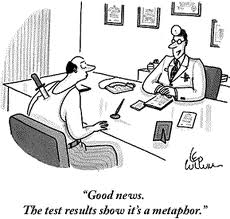

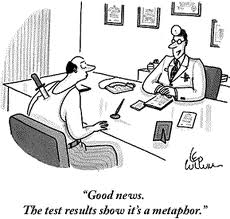

The Reynolds Lecture for 2012, presented at Emory & Henry College, reflects on Frye’s view of metaphor only toward the end, I’ve often felt that theories of metaphor–at least those I’m familiar with–turn out to be founded on principles of similarity, comparison, analogy, or likeness. Frye’s theory is unique in that it’s founded on sameness or identity. I try to consider some of the implications of that view in the conclusion of the lecture.

What’s a Meta For?

Reynolds Lecture, Emory & Henry College, 28 March 2012

Robert D. Denham

It goes without saying, a phrase we use to mean that we should say at once, how honored I am to be the Reynolds Lecturer for 2012 and on the occasion of the 175th anniversary of the founding of Emory & Henry College, where I worked and played for some twenty‑three years. Early on in my tenure here the dean of the college, Dan Leidig, assigned me to chair the Reynolds Lecture Committee, and so I had the good fortune of helping bring to campus such eminent humanists as Helen Vendler, James Redfield, John Simon, Wayne Booth, and Northrop Frye, among others. I never dreamed, of course, that I would be joining their ranks as a Reynolds Lecturer, and I naturally feel that this is an instance of the ridiculous linking up with the sublime. At the same time, we all stand on the shoulders of giants, which is both humbling and elevating. The first Reynolds lecturer at Emory & Henry––in 1963––was Norman Cousins, peace activist and long‑time editor of the Saturday Review. Two years later the president of the college, William Finch, whose son Tyree has joined us tonight, introduced the second Reynolds lecturers (there were two that year, on successive nights), both distinguished poets and critics, John Crowe Ransom and Reed Whittemore. The shoulders of giants, indeed.

I’ve called my lecture tonight “What’s a Meta For?”––a title stolen from a quip by Marshall McLuhan: “Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a metaphor?” McLuhan, too, was a thief: he was twisting the end of a line from Browning, “Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?” That is, the notion of an ideal world, which we may never attain, nevertheless motivates us to seek something better than what we’ve now got: it may elude our grasp but in our Utopianism we still reach for it. I think metaphor in its most radical forms may have something to do with our linguistic reach exceeding our grasp, which is a notion I’ll come back to. Rather than trying to define tonight what metaphor is, I’ll be reflecting on some of the contexts in which we encounter metaphor.

Metaphor is, of course, along with myth, one of the basic building blocks of literature. John Keats’s masterful Ode on a Grecian Urn begins with three metaphors. Keats is speaking to the urn: he addresses it by saying, “Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness, / Thou foster-child of silence and slow time, / Sylvan historian.” In these nouns of direct address Keats, who was in his early twenties when he wrote the poem, is identifying the urn with a bride, a child, and a historian. The suggestions that issue from the three metaphors are fairly complex. Of course everyone knows that an urn is not a bride, and yet Keats is saying that it is a bride and not just that: she’s a bride who’s still chaste. Furthermore, she’s married to quietness. And she is also a child, or rather a foster‑child, who has been nourished by her adoptive parents, silence and slow time. We could spend the rest of the evening investigating the magical language of Keats’s poem––its metaphors, paradoxes, and puns. The point I want to make is that the extraordinary uses to which Keats puts figurative language is commonplace among poets. Here’s another, the opening lines of one of Jeff Daniel Marion’s old Chinese poet poems: “Over the river this quarter moon / tilts in its dark well, / a gleaming dipper / spilling October.” Here the moon is a gleaming dipper, and the heavens are a dark well. This is the way poets talk.

Metaphor, however, is an aspect of language that belongs not just to poets and novelists and playwrights. In a story in a recent issue of a college student newspaper I read about the soccer team’s “dream season, the “noise” that it took to wake the team up from its dream, about a “sudden death” period, about the opposing team’s drawing “first blood.” And I read in a college catalogue, a most unpoetic document, about “cultivating students’ sensitivity,” students being, in this metaphor, something you run a plow through, like dirt. In one of her “Messages from the President” in the alumni journal Emory & Henry’s Rosalind Reichard quotes George Peery, class of 1894, who forty years later became the governor of Virginia, as saying that the ideals “cultivated” at Emory & Henry deeply influenced his life. That’s the plowing metaphor again. The Indo‑European root for “cultivate” means to revolve or move around, which is what the plow does to the field. In the most recent alumni journal President Reichard moves from the garden to the sea, speaking about the “tides of influence” that have rippled forth from Emory & Henry. Perhaps this metaphor comes from her inaugural address, where she quoted an alumnus as saying that Emory & Henry continues to send “out tides of influence that touch the whole hungry soul of man.” Because the alumnus begins with a watery metaphor, he would doubtless have been better served, at least to those not given to mixed metaphors, to have said “the whole thirsty soul of man.” A final example from President Reichard comes in her message in the recent annual report. “Emory & Henry,” she says, “is a beacon of hope envisioned by her founders.” And then she extends the metaphor saying that the college is a glowing light in the heart of many of us that will shine brightly for many decades. So here we have an administrator and a mathematician, Rosalind Reichard, using one of the key elements of the language of poetry.

But back to more mundane texts, like college catalogues. I pick one up and read about the holder of a degree, about the fortifying of students’ minds, about launching on a voyage of discovery, about the important voice the students have in shaping programs (two metaphors there), about higher education being a marketplace of ideas, about instructional tools, about a semester spanning the summer months, about the library as an electronic gateway, about instructional software and flexible seating, about developing a strategy for accomplishing goals, and so on. So even in the most unpoetic and leaden prose, we find metaphor. (“Leaden” in that sentence is of course also a metaphor, one that derives from metallurgy.)

Or one can turn to the daily press, which wouldn’t on the face of it seem to be a particularly fertile field for metaphor. (Note “fertile field.”) In the headlines of the Roanoke Times I read that the GOP leader will step down, that a mountain is hiding a quiet threat, that the media are too soft on the president, that three-year college degrees are a fast track, that a basketball player has come to the end of the road, that loyalists slam Cuban defectors. Here are two from a David Brooks editorial: (1) Mitt Romney is a corporate vulture and (2) when people read Ron Paul the scales fall from their eyes. This last one comes from the account of the conversion of Ron Paul’s namesake, St. Paul, a.k.a Saul, on the road to Damascus. In Acts we’re told that “something like scales fell from his eyes” and he could see again. That’s simile, not metaphor. But the simile has become a metaphor in common parlance, referring to a person who has come to a sudden realization. “Road to Damascus experience” is a metaphor growing out of the same story. Here are a few more from the headlines in the New York Times of 17 January 2012: “Romney Opponents’ Main Target in G.O.P. Debate,” “For Romney’s Rivals Time Is Running Out,” “Romney Keeps Eye on Obama,” “The Invisible Hand behind Wall Street Bonuses,” “Iran Face‑Off” (that one’s from hockey), “Wikipedia To Go Dark,” “Israelis Facing a Seismic Rift Over Role of Women,” and “Bang for the Buck.”

Continue reading →