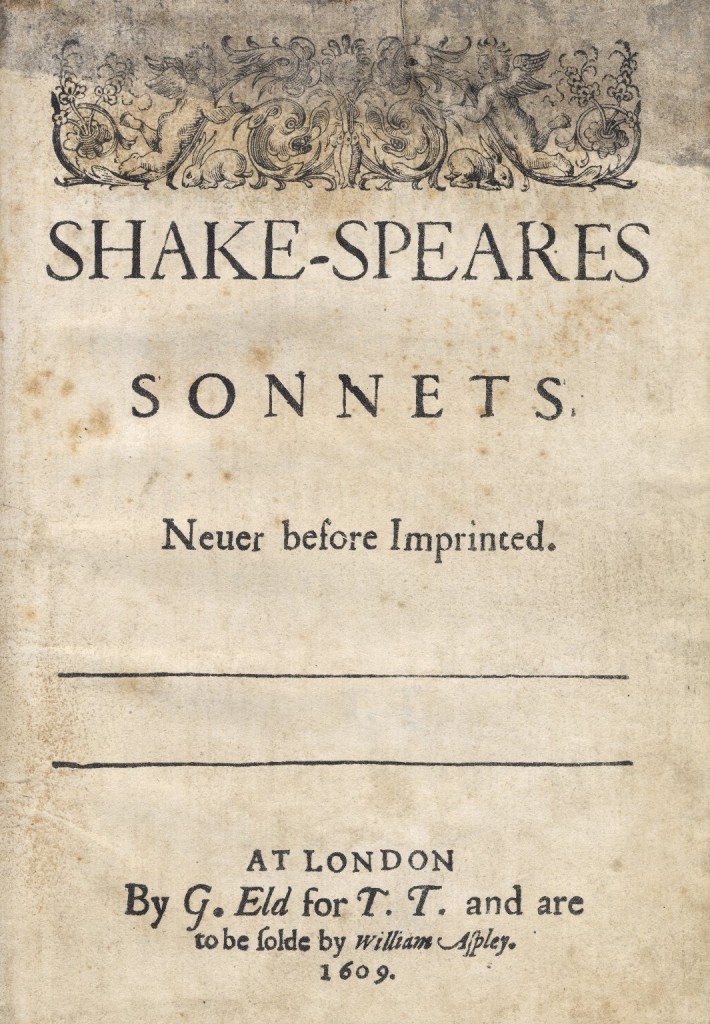

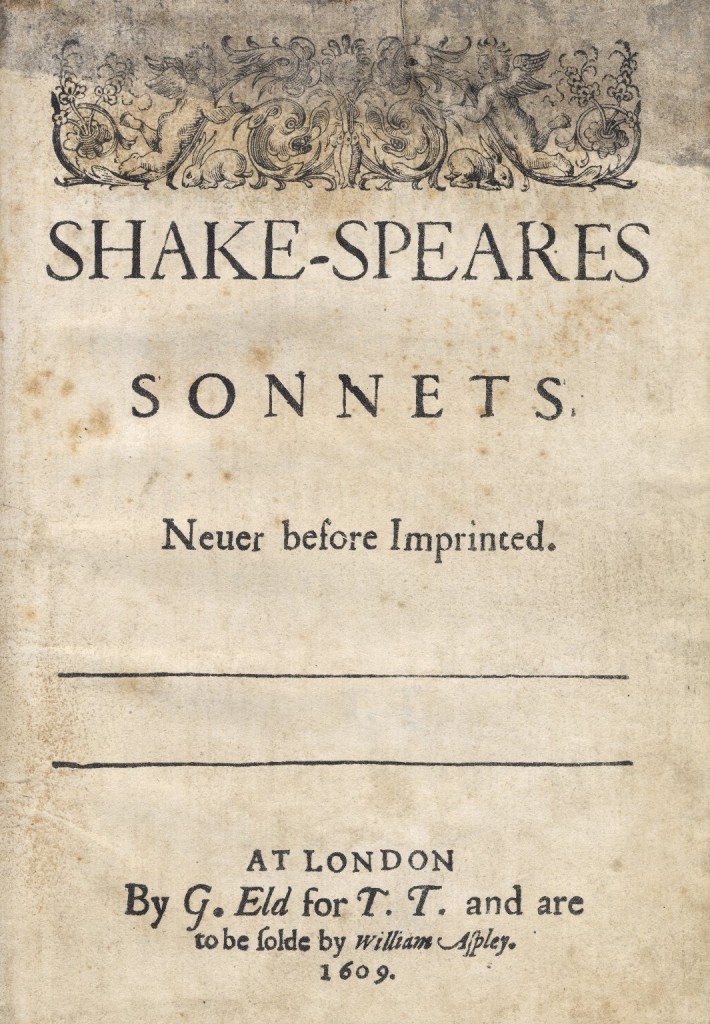

On this date in 1609 Shakespeare’s sonnets were published for the first time.

Frye in “How True a Twain”:

What one misses in Shakespeare’s sonnets, perhaps, is what we find so abundantly in the plays that it seems to be Shakespeare’s outstanding characteristic. This is the sense of human proportion of the concrete situation in which all passion is, however tragically, farcically, or romantically, spent. If the sonnets were new to us, we should expect Shakespeare to remain on the human middle ground of Sonnets 21 and 130; neither the quasi-religious language of 146 nor the prophetic vision of 129 seems typical of him. Here again we must think of the traditions of the genre he was using. The human middle ground is the area of Ovid, but the courtly love tradition, founded as it was on a “moralized” adaptation of Ovid, was committed to a psychological quest that sought to explore the utmost limits of consciousness and desire. It is this tradition of which Shakespeare’s sonnets are the definitive summing-up. They are a poetic realization of the whole range of love in the Western world, from the idealism of Petrarch to the ironic frustration of Proust. If his great predecessor tells us all we need to know of the art of love, Shakespeare has told us more than we can ever fully understand of its nature. He may not have unlocked his heart in the sonnets, but the sonnets can unlock doors in our minds, and show us that poetry can be something more than a mighty maze of walks without a plan. From the plays alone we get an impression of an inscrutable Shakespeare, Matthew Arnold’s sphinx, who poses riddles and will not answer them, who merely smiles and sits still. It is a call to mental adventure to find in the sonnets the authority of Shakespeare behind the conception of poetry as a marriage of Eros and Psyche, an identity of a genius that outlives time and a soul that feeds on death. (Fables of Identity, 105-6)

Bryan Ferry‘s musical adaptation of Sonnet 18 after the jump.

Continue reading →