A Marylhurst University student, Sarita Ruckert, has posted her essay on The Great Code and the books of Esther and Jonah here.

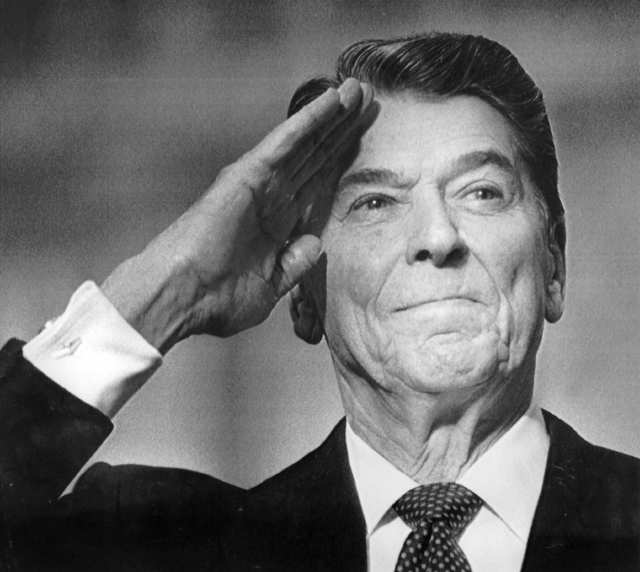

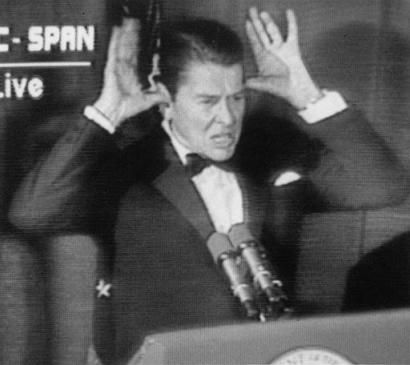

More on Reagan

Further to Joe’s post, more Frye on Reagan:

Of course it takes some effort to become more self-observant, to acquire historical sense and perspective, to understand the limitations that have been placed on human power by God, nature, fate, or whatever. It was part of President Reagan’s appeal that he was entirely unaware of any change in consciousness, and talked in the old reassuring terms of unlimited progress. But the new response to the patterns of history seems to have made itself felt, along with a growing sense that we can no longer afford leaders who think that acid rain is something one gets by eating grapefruit. I wish I could document this change from recent developments in American culture, but I am running out of both time and knowledge. It seems clear to me, however, that American and Canadian imaginations are much closer together than they have been in the past. (CW 12, 653)

Both Governor Reagan and the local SDS issued statements, and there is a curious similarity in their statements. They both say that the people’s park was a phoney issue, and that the real cause was a conspiracy—the Governor says of hard-core student agitators, the SDS says of right-wing interests operating “probably at the national level.” Both are undoubtedly right, up to a point. There is a hard core of student agitators: one of them was grumbling in the student paper, a day or two before the lid blew off, that “not a goddam thing was happening at Berkeley,” and that something would have to start soon because Chairman Mao himself had said, in one of his great thoughts, that revolution is no child’s play. On the other side, Governor Reagan is clearly staking a very ambitious career on the support of voters who want to have these noisy young pups put in their place once and for all. Both are very pleased with the result: the Governor is visibly admiring his own image as a firm and sane administrator, and the SDS are delighted that the police have “over-reacted” so predictably and helped to “radicalize the moderates.” But the more one thinks about these two attitudes, the clearer it becomes that the militant left and the militant right are not going in opposite directions, even when they fight each other, but in the same direction. For both the Governor and the SDS, the university is ultimately an obstacle, which will have to be destroyed or transformed into something unrecognizable if their ambitions are to be fulfilled. (CW 7, 386-7)

At Berkeley, one sees clearly how the supporters of Governor Reagan and the supporters of SDS are the same kind of people. The radical talks about the thoughts of Chairman Mao, not because he is really so impressed by those thoughts but because he cannot endure the notion of thought apart from dictatorial power. The John Bircher uses slightly different formulas to mean the same thing. In the past week I have seen, and heard about, the most incredible acts of police brutality and stupidity against the students. And yet even this is not one society repressing another, but a single society that cannot escape from its own bungling. Whatever we most condemn in our society is still a part of ourselves, and we cannot disclaim responsibility for it. (ibid., 392)

The Soviet Union is trying to outgrow the Leninist dialectical rigidity, and some elements in the U.S.A. are trying to outgrow its counterpart. But it’s hard: Reagan is the great symbol of clinging to the great-power syndrome, which is why he sounds charismatic even when he’s talking the most obvious nonsense. (CW 5, 398)

BILL MOYERS: I’ve often thought that one of the secrets of Ronald Reagan’s appeal was that he was able to make Americans feel as if we were still the mighty giant of the world, still an empire, even as around the world we were having to retreat from the old presumptions that governed us for the last fifty years. Did you see any of that in the Reagan appeal?

FRYE: Oh yes, very much so. It’s the only thing that explains the Reagan charisma. In fact, I think that what has been most important about Americans since the war is that they have been saying a lot of foolish things—the Evil Empire, for example—but doing all the right ones. I think nobody but Nixon could have organized a deal with China, for example. (CW 24, 893-4)

Todd Alcott: “Television is a Drug”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jaWsewOKhgw

Further to Joe’s post, Todd Alcott’s “Television is a Drug”.

What’s Wrong with the New York Times? (2)

“Obambi”. That’s Maureen Dowd‘s nickname for Obama which she employed right through the primaries until his nomination in 2008. The problem with it? Well, it of course has nothing to do with anyone recognizable as Barack Obama, a remarkably capable politician who, by the time he’d announced his candidacy, had already made a career of overseeing the self-destruction of his opponents. But Dowd pushed the “Obambi” conceit for almost two years because she could. As is regularly the case, she lacked the discipline to weigh whether or not she should. This, remember, is the same person who during the 2000 election gleefully perpetuated the fiction that Al Gore claimed to have “invented the internet”, and suggested that he is “so feminized” that he is “practically lactating”.

And that’s a pattern of behavior with Dowd which is disturbing for at least a couple of reasons. The first is that she never lets a fact get in the way of a low blow she regards as clever, and the second is that she has an unmistakable tendency to feminize males in order to dismiss them — and moreover does so almost exclusively with Democrats, calling them “the mommy party” (you can guess who “the daddy party” is). She likewise occasionally masculinizes women for much the same purpose, most especially Hillary Clinton — or “Hillzilla”, as Dowd dubbed her during the primaries. Gender stereotyping is one of a number of strategies that Dowd regularly resorts to in place of anything that might be characterized as responsible criticism.

Here are some notable examples of Dowd’s effort to emasculate Obama — because girly-men are, you know, self-evidently a joke that everybody gets: “diffident debutante“, “America’s pretty boy“, “effete“, “emotionally delicate“, “weak sister“, “legally blonde“. Ask yourself: Does any of this even remotely coincide with your estimation of the man, however you feel about his politics? And why diminish him with feminine comparisons? What is going on here?

This is just one thread in a whole skein of such behavior. Media Matters for America has a more complete catalogue of Dowd’s persistent use of gender stereotypes here. Allegedly feminized men are not fit to govern according to Dowd, and most certainly not when they are Democrats. But “tough guys” like John McCain (who once publicly called his wife a cunt) can, when the mood is upon her, set Dowd’s atavistic heart aflutter. It is so persistent a pattern that it’s difficult not to wonder what lies behind it.

This matters because the Times is the flagship of a supposedly “liberal media”, and its opinion makers still draw a lot of water. Dowd in particular plays the celebrity circuit with personal profiles in mass circulation magazines and appearances on television whenever she has a book to sell, such as the widely panned Are Men Necessary? We live in a world where we’re apparently required to put up with the lies that Fox News manufactures on an hourly basis in the name of “balance”. So it’d be nice if the paper of record didn’t propagate twice a week the neurotic, unfunny, unclever babble of Maureen Dowd, which gets said not because it necessarily has anything to do with anything that is actually happening, but because it is formulated by someone who isn’t responsible enough not to say it.

Saturday Night Beethoven

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nt7pPKXDhPc

The anniversary of the first performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony passed earlier this week, so here is the entire thing, conducted by Arturo Toscanini.

Frye on Reagan, the Pope, and the Illusion of Television

Further to the previous post, here is some cultural studies avant la lettre: Frye on Reagan, the Pope, and “the prison of television.”

[282] Television brings a theatricalizing of the social contract. Reagan may be a cipher as President, but as an actor acting the role of a decisive President in a Grade B movie he’s I suppose acceptable to people who think life is a Grade B movie. The Pope, whose background is also partly theatrical, is on a higher level but the general principle still holds. It goes with reaction, identifying the reality with the facade. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if, just for once, it could be true that Father knows best? Emotional debauch of father-figuring. (Notebook 27)

[492] American civilization has to de-theatricalize itself, I think, from the prison of television. They can’t understand themselves why they admire Reagan and would vote for him again, and yet know that he’s a silly old man with no understanding even of his own policies. They’re really in that Platonic position of staring at the shadows on the wall of a cave. The Pope, again, is another old fool greatly admired because he’s an ex-actor who looks like a holy old man.

[493] Watching a television panel of journalistic experts discussing the (Bush-Dukakis) election, it seemed to me Plato’s cave again and Plato’s eikasia, or illusion at two removes–show business about show business. All one needs to know about such horseshit is how to circumvent whatever power it has. I’m trying to dredge up something more complex and far-reaching than just the cliché that elections today are decided by images rather than issues–they always were. It’s really an aspect of the icon-idol issue: imagination is the faculty of participation in society, but it should remain in charge, not passively responding to what’s in front of it. Where does idolatry go in my argument? End of Three? (Notebook 44)

[85] Why do Americans continue to cherish Reagan, including millions of Americans who know he’s an ass? I think they’re bored by their own indifference to the world, but can only focus their minds on a boob-tube leader. (Notebook 50)

Oswald Spengler

On this date Oswald Spengler died (1880 – 1936).

Frye’s “Spengler Revisted” can be found here.

Frye in one of the late notebooks:

Spengler: I never did buy his “decline” thesis, which I realized from the beginning was Teutonic horseshit, closely related to the Nazi hatred for all forms of human culture. (Well, not just Nazi; Stalin had just as much of it.) No, as I’ve said, what struck me was, first, the sense of the interpenetration of historical phenomena, a conception of history in which every phenomenon symbolizes every other phenomenon.

Along with that came the conception of a culture in which works of culture show a progressively aging process. You have pure tradition in primitive societies, where conventions just repeat over and over, and you have a culture in which tradition accruse a self-consciousness in regard to itself, so that it must be where it is: i.e. Beethoven could only have come between Mozart and Wagner. This growth of self-awareness in tradition is recapitulated in the life of the poet or artist, which gives biography a genuine function in criticism. (CW, 6, 649)

Joan Wyatt: The Cruciform Woman Image Then and Now

Professor Joan Wyatt is the Director of Contextual Education at Emmanuel College

In the spring of 1979 while living in Port Hope, Ontario, I read in the Globe and Mail that Almuth Lutkenhaus’s sculpture Crucified Woman had been installed at Bloor Street United Church. She was in the narthex during Holy Week and in the sanctuary on Good Friday. The outrage of some was expressed when someone at Toronto South Presbytery charged Cliff Elliot, the incumbent minister at the time, with heresy. The support of others helped Presbytery to dismiss the charges.

Last year, marking 30 years since this remarkable occasion, many gathered at Emmanuel College to hear Sophie Jungreis, a Jewish artist, Nevin Reda, a Muslim academic, and Margaret Burgess and Janet Ritch, literary scholars, reflect on what the image of Crucified Woman evokes today. Toronto lawyer and scholar Nella Cotrupi read a stunning poem.

The evening concluded with many walking by candlelight to Bloor Street United Church, where the Easter Vigil service celebrated images of women cruciform and rising. Johan Aitken, professor emerita from OISE and an original member of the committee who brought the installation in 1979, related her experiences of that time. Visual images of women suffering and rising around the globe enhanced the service.

I graduated in 1986, when Lutkenhaus’s gift of Crucified Woman was finally, after a protracted debate, accepted by Victoria University. Doris Dyke, a professor at Emmanuel College, along with a group of students who called ourselves the “Uppity Women,” planned an event to mark her installation in the garden behind Emmanuel College. The Friday evening showcased women’s stories, gifts, and accomplishments. The next day a well-attended outdoor worship service featured the hymns of the late Sylvia Dunston, liturgical dance under the direction of Alexandra Caverly Lowery, and preachers Doris Dyke and Cliff Elliot. I was the worship leader and was thrilled to complete my years at Emmanuel College, where the debate of what would it mean to have Crucified Woman at a theological School had shaped my understanding of the challenges of feminist thought. The service was a satisfying occasion, indicating that the academy and the Church recognized both the rights and the suffering of women.

May 14–15, 2010, women and men once again will gather to reflect on what the symbol of a cruciform Woman evokes in our culture today. Ojibway elder Marjory Noganosh will lead the opening ceremony and present, along with social activist Pat Capponi, and photojournalist Rita Leistner. Come listen, reflect, and join this ongoing conversation, a conversation that also invites submissions to be considered for publication.

Biographies of the speakers and workshop presenters, as well as of the dancers and musicians who will be performing at the event, after the jump.

TGIF: North Minehead By-Election

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vlmGknvr_Pg

It’s a hung parliament in Britain, and it’s not yet clear what will happen next. Here’s the classic Monty Python North Minehead By-Election sketch, featuring Mr. Hilter, Mr. Bimmler, and Ron Vibbentrop.

Further Thoughts on Frye and Machiavelli

Thank you for these posts on Machiavelli (here and here). That we have derived the word hypocrite from the Greek word for actor called up for me the image of Ronald Reagan, an actor whose enormous appeal as a politician had much to do with his ability to wear a mask and speak words that were complete illusions. It also called to mind a passage in Stendhal’s Le Rouge et le Noir, where the narrator observes of Julien Sorel, a young Tartuffe in training and a secret admirer of Napoleon, that he never felt comfortable in a social or political context–this would be during the very reactionary period of Charles X– unless he were saying something very different from what he actually believed.

I also thought of Michael’s earlier post quoting Frank Rich in the New York Times who, in contrasting Obama with his Republican opponents, refers to Frye’s definition of a good leader. When I first read that post I wondered where Frye had given such a definition. It appears to be from The Fools of Time and the discussion of the nature of the strong order figure in the context of Shakespearean tragedy. I have extracted a couple of passages below.

We are apt to assume, like Brutus, that leadership and freedom threaten one another, but, for us as for Shakespeare, there is no freedom without the sense of the individual, and in the tragic vision, at least, the leader or hero is the primary and original individual. The good leader individualizes his followers; the tyrant or bad leader intensifies mass energy into a mob. Shakespeare has grasped the ambiguous nature of Dionysus in a way that Nietzsche (like D. H. Lawrence later) misses. In no period of history does Dionysus have anything to do with freedom; his function is to release us from the burden of freedom. The last thing the mob says in both Julius Caesar and Coriolanus is pure Dionysus: “Tear him to pieces.”

And this passage:

Society to the Elizabethans was a structure of personal authority, with the ruler at its head, and a personal chain of authority extending from the ruler down. Everybody had a superior, and this fact, negatively, emphasized the limited and finite nature of the human situation. Positively, the fact that the ruler was an individual with a personality was what enabled his subjects to be individuals and to have personalities too. The man who possesses the secret and invisible virtues of human nature is the man with the quiet mind, so celebrated in Elizabethan lyric poetry. But such a man is dependent on the ceaseless vigilance of the ruler for his peace.

This view of social order, with its stress on the limited, the finite, and the individual, corresponds, as indicated above, to Nietzsche’s Apollonian vision in Greek culture. That makes it hard for us to understand it. We ourselves live in a Dionysian society, with mass movements sweeping across it, leaders rising and falling, and constantly taking the risk of being dissolved into a featureless tyranny where all sense of the individual disappears. We even live on a Dionysian earth, staggering drunkenly around the sun. The treatment of the citizens in Julius Caesar and Coriolanus puzzles us: we are apt to feel that Shakespeare’s attitude is anti-democratic, instead of recognizing that the situation itself is pre-democratic. In my own graduate-student days during the nineteen-thirties, there appeared an Orson Welles adaptation of Julius Caesar which required the hero to wear a fascist uniform and pop his eyes like Mussolini, and among students there was a good deal of discussion about whether Shakespeare’s portrayal of, say, Coriolanus showed “fascist tendencies” or riot. But fascism is a disease of democracy: the fascist leader is a demagogue, and a demagogue is precisely what Coriolanus is not. The demagogues in that play are the tribunes whom the people have chosen as their own managers. The people in Shakespeare constitute a “Dionysian” energy in society: that is, they represent nothing but a potentiality of response to leadership.