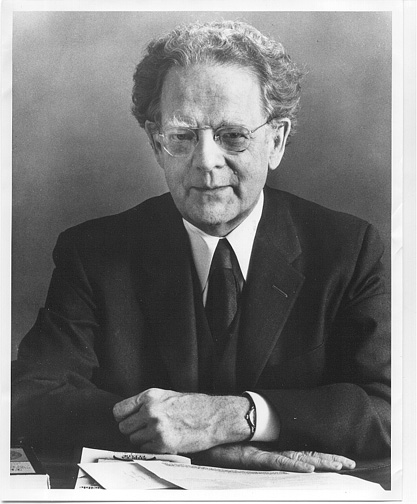

Bob Rodgers’s link featuring an excerpt from Frye’s lectures on the Bible is now working. Please have a look.

“Reasons Literature Alone Can Satisfy”

Readers of The Educated Imagination may be interested in this post on Rohan Maitzen’s blog Novel Readings. Responding to a review of Louis Menand’s The Marketplace of Ideas, Professor Maitzen provides a cogent reflection on the dangers of emphasizing the practical benefits of literary study, at the expense of the actual subject matter of the discipline. She argues that “We need to justify the study of literature for reasons literature alone can satisfy.”

Update from the Frye Festival

One of the delights we have every April is introducing Frye to authors who have never heard of him and are curious to know more, as happened, for example, when Bernhard Schlink was here in 2004. Sometimes we are surprised when an author reveals a personal connection to Frye that we didn’t know about. Last year Don McKay, one of Canada’s great poets, took delight in telling the story of his mother’s encounter with Frye in the 1930s, when she took a class from him that influenced her at the time and later, toward the end of her own life, came back to inspire her when she wrote her memoirs. Andy Wainwright, Ross Leckie, and others studied with Frye and have fond memories. Peter Sanger has a longstanding interest in Frye; and, unless I’m mistaken, also studied with him. Richard Ford was familiar with Frye from his student days in the 60s. (Ford’s complete conversation with Globe and Mail’s Books Editor Martin Levin can be seen via the festival website’s U-Tube link.)

Robert Bly, who was here in 2001, said, in accepting our invitation, “Frye is one of my favorite people.” There’s a lot of common ground between the two that would be worth exploring, even if the direct influence each way is perhaps minimal. Blake’s “the tigers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction” is where they both begin, in their thinking about education. The idea of freedom is at the centre of everything they do. Neither shies from talking about and mapping the spiritual world, even when such activity is out of fashion. But what especially interests me is Bly’s idea of ‘deep image’ in comparison with Frye’s analysis of existential or ecstatic metaphor. Though ‘deep image’ suggests a location in the psyche, Bly prefers to think of the image as a place “where psychic energy is free to move around” (as quoted in Kevin Bushell’s essay “Leaping Into the Unknown: the Poetics of Robert Bly’s Deep Image”). Frye says, “Metaphor is the attempt to open up a channel or current of energy between subject and object” (as quoted in Bob Denham’s Northrop Frye: Religious Visionary and Architect of the Spiritual World, p. 70). Ecstatic metaphor, at the top of the ladder of metaphorical experience, creates “a sense of presence, a sense of uniting ourselves with something else” (Frye words, as quoted by Bob Denham, p. 72). The free flow of psychic energy is what counts for both. For Bly (at least the early Bly) a true or authentic poem has to involve the “leap” from the conscious, everyday world to the unconscious, universal world. For Frye it’s the gap between subject and object that’s obliterated in ecstatic metaphor. Frye’s is, if anything, a more expansive concept.

Over the years Bly moved deeper and deeper into the study of Jung and Jung’s concept of the unconscious. Throughout the nineties he worked with the Jungian analyst Marion Woodman and in 1998 they published their book The Maiden King. Frye’s interest in Jung was also deep and important. As Bob Denham says, “Frye sometimes expressed anxieties about being considered a Jungian, but he was much more deeply immersed in Jungian thought than is commonly imagined” (Religious Visionary, p. 196). Jung’s Psychology and Alchemy is a rich source for Frye, as Bob Denham wonderfully recounts. “In Anatomy of Criticism, alchemy is seen as a repository of archetypes (rose, stone, elixir, flower, jewel, fire).” (Religious Visionary, p. 194).

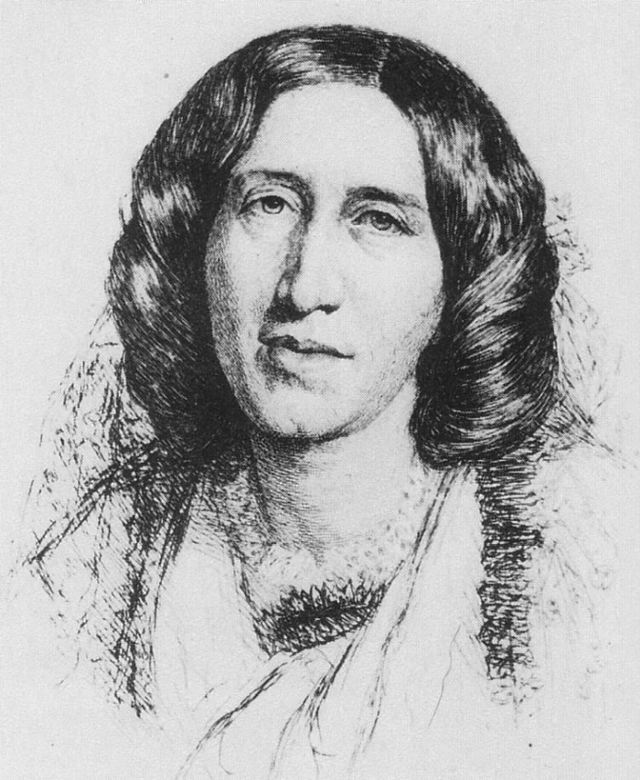

Daniel Deronda’s “Double Heroine”

Joe Adamson notes that the “double-heroine” structure is worthy of further study whether it be (and I hope I am not over-reading here) in canonical literature or in popular literature. In his response to my post, he mentions one of my favourite novels, Daniel Deronda by George Eliot. The novel itself was added to my field exam bibliography late in the process, and I remember groaning when it happened (and also questioning why a realist novelist was to be included). However, as I started to read the novel, I quickly became entranced by it and ended up getting through it in a single day. But, after thinking about Joe’s response, I’d have to say our readings are different.

It seems to me that Daniel Deronda’s selection of Mirah isn’t that he selects the “dark Jewish heroine” as a rebellious move, but rather that the choice is, in many ways, a reinscription of Frye’s structure of romance. The great “surprise” of Daniel Deronda is the protangonist’s realization that he is Jewish and not Christian. His marrying Mirah is really, I think, quite similar to Ivanhoe – although in Eliot’s novel, what has been reversed or inverted is not structural, but religious. That is, the structure of the marriage hasn’t been disrupted nor has the definition of community – if anything, Deronda is the sort of pharmakos character (rather than hero) who must be accepted by the Jewish community.

Robert B. Parker, 1932 – 2010

Another sad death to report is that of Robert B. Parker, creator of the Boston private detective Spenser (whose first name was never given, but who said that his last name was spelled with an ’s’, “like the poet.”) It’s appropriate to pay tribute to Parker on this blog, both because Frye liked reading detective stories, and because Parker had a PhD in English from Northeastern. Several of his novels feature academic satire. He died at his desk, a writer to the last moment.

Steven Axelrod’s tribute at Salon.com (”How the crime novelist taught me to stand up for myself and taught my son about the carnal pleasures of reading”) can be found here. Axelrod’s piece is noteworthy for the way it suggests the liberating possibilities inherent in popular fiction.

Kate McGarrigle, 1946 – 2010

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Enc8KEzdYY

Frye and Science

In Notebook 27 Frye writes:

I’m giving up the “science” bit in AC: it’s impossible to explain to this generation of critics what I mean. I never did have the analogy of the physical sciences in mind: the model was always social science, man studying himself. What I thought of was a merging of criticism with semiotics and linguistics. When critics keep saying that there can’t be a science of criticism, what they’re really saying is “I can’t and won’t write this kind of criticism,” and I can’t say they’re wrong because I can’t & won’t write it myself. People will write it some day, and I thought it might be a good thing to alert the critics of the 50’s to the ultimate end of what they were actually doing. But if it’s just a prophecy with no present practical use, the hell with it. (CW 5, 85)

As Michael Dolzani says, Frye’s scientific heroes were of the visionary kind––Whitehead, Jeans, Alexander, Bohm. I’ve always wondered whether Frye was familiar with the paradigm theory in Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions––a theory that would seem to have attracted him. He owned a copy of the book, but I think there’s no evidence that he ever read it, though he seems to have discussed it in an interview with Gilbert Reid. Frye had more than a casual interest in science fiction and in the views of new‑age scientists––what he called “the Tao of physics people” (Ken Wilber, Fritjof Capra, et al.).

Frye was familiar with several popular accounts of science. He read C.P. Snow’s The Two Cultures, James Gleick’s Chaos: Making a New Science, Isaac Asimov’s The Intelligent Man’s Guide to Science and The Neutrino: Ghost Particle of the Atom, and he read as well several of Carl Sagan’s books (Bocca’s Brain, The Cosmic Connection, and The Dragons of Eden).

Frye’s library contains annotated editions of a wide variety of other books on science, including Edwin Burtt’s The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science, Stewart Copinger Easton’s Roger Bacon and His Search for a Universal Science, David Hay’s Exploring Inner Space: Scientists and Religious Experience, his colleague John Irving’s Science and Values, Gordon N. Patterson, Message from Infinity: A Space-age Correlation of Science and Religion, and Rudy Rucker’s, Infinity and the Mind: The Science and Philosophy of the Infinite.

Books that Frye owned but did not annotate include Tobias Dantzig, Number: The Language of Science: A Critical Survey Written for the Cultured Non-mathematician, Karl Pearson’s The Grammar of Science, Oliver R. Reiser’s The Integration of Human Knowledge: A Study of the Formal Foundations and the Social Implications of Unified Science and Unified Symbolism for World Understanding in Science, and C.H. Waddington’s The Scientific Attitude.

At school I was taught that substances keeping form & volume were solids, those keeping volume but not form liquids, & those keeping neither gas. Even then I could see that there ought to be a fourth class keeping form but not volume. And there is a tradition, though admittedly a very speculative one, which says that there is a fourth class of this kind, & the one that includes all organisms or living beings. Also, that just as solids, liquids & gases have a symbolic connexion with, respectively, earth, water & air, so organisms, especially warm-blooded animals, are units of imprisoned fire. (CW 13, 208)

Hump Day Music Video

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-FjSchBoch0

I’m sick and have lost my voice, so I’ll have to let others do my singing for me.

Here’s another vintage REM video, “Shiny Happy People”, featuring the exquisite Kate Pierson of that other band from Athens, Georgia. (I will find a reason to post something by them sometime soon!)

The Bible and Literature with Northrop Frye: Proposed DVD

We are delighted to present the following announcement from Bob Rodgers:

In 1981-82, as producers at the then U of T Media Centre, Bill Somerville and I recorded Northrop Frye’s classic lectures and seminars on The Bible And Literature, and have recently had them converted from analog video to the digital format. Now an independent producer, I am in discussions with Carol Moore, Chief Librarian at the Robarts Library, U of T, to adapt this material to DVD format for global distribution in the educational market. Each of 24 programs will include a full video-taped lecture, a related seminar, and interactive contextual and explanatory notes.The Main Menu reads as follows:

The Bible and Literature with Northrop Frye

Program One

An Approach to the Bible and Translations of the Bible (The Lecture)

Lecture Breakdown

Seminar Segment

Lecture Transcript

References for Lecture One

Study Guide

Series Synopses

The video and support materials are designed for private study, at home or in a library, just like a book, but with interactive references at a click. As Frye intended, the information is aimed at undergraduate students lacking the basic familiarity with the Bible he believed was needed to respond adequately to western literature. Secondary applications are for use in seminars or informal study groups where this or that section of the DVD may be used for stimulation or talking points by the seminar or group leader.

For a short video clip from the lecture segment of the pilot DVD, go to http://davidsharp.ca/Frye/. For technical reasons the picture quality of this clip is inferior to that of the DVD. We have also produced a test pilot of Program One and have a limited number of copies to send to “Friends of Frye” who would like to receive a copy by mail free of charge. If you would like one, please send us your postal address and we will do our best to get it out to you.

What we would like in return is your assessment of the value of the series, a testimonial or endorsement if it meets with your approval, and an indication as to whether or not your institution is likely to aquire it. While some units will be available earlier, we anticipate completion of the full 24 part series to take 18 months from the start of production.

We are receiving queries about this undertaking from across Canada, the US, and abroad. Your response would be much appreciated as we bring it to fruition.

Contact: Bob Rodgers, Producer …. 416 504 2196….< r.rodgers@primus.ca>

ARCHIVEsync…. 110 The Esplanade, Suite 611. Toronto. Ontario M5E 1X9

Word and Spirit

Several years back I puzzled over the conjunction of Word and Spirit in Frye’s later writing, concluding that they did in effect serve as a great code to his words of power. Here’s an adaptation of what emerged:

Word and Spirit in their capitalized forms appear, as one would expect, throughout his work, and in numerous contexts. In The “Third Book” Notebooks, “Word” is often associated with what Frye calls the Logos vision and “Spirit” with the traditional Holy Spirit. But “Word” and “Spirit” do not appear in Frye’s writing as a dialectical pair until the late 1970s, and before the writing of Words with Power only three times. In one of the notebooks for The Great Code he refers in passing to “pericopes of Word & Spirit” (CW 13, 268), and when he is trying to work the relation between the cycle, which he eventually abandoned, and the axis mundi, which became his primary spatial metaphor, he speculates, in an intriguing entry, that “the up and down mythological universes form a wheel, and the wheel is the cycle of recurrence. In the cyclical vision everything becomes historical, and there is no Other except the social mass. The impulse to plunge into that is strong but premature. Something here eludes me. The answers are in interpenetration and Thou art That, but the real individual is not the illusory series of phantasmal egos in time: it’s the total body of charitable articulation. The assumptions underlying this articulation are Word & Spirit. Probably the crux of the whole book” (CW 13, 327). Here Frye appears to have the answer but does not know what the question is. What are the two things that interpenetrate in this passage, a difficult one to gloss? Thou (the individual) and That (the social mass)? The self and the Other? “Charitable articulation” could be seen as Frye’s final cause. The material cause would then be “Word” in its several senses, the formal cause “Spirit,” and the efficient cause criticism in all of its Frygian permutations: its aphorisms, commentary, schema, imaginative free play, investigations of myth and metaphor, analogical linkages, sober speculations, creative flights of fancy. The word “articulation” reminds us that Frye’s universe is a linguistic one. “I’m glad I’m not concerned with belief,” he says, “but only with trying to understand a language” (CW 13, 303), which is reminiscent of his later statement about not believing in affirmations but only in the verbal formulas he constructs (CW 5, 145). These formulas, he goes on to say, “seem to make sense on their own, & seem to me something more objective than merely getting something said the way I want it said. I hope (but again it’s not faith) that this is the way the Holy Spirit works in me as a writer” (ibid.). Frye consistently focused on finding language to articulate the substance of his vision (spirit), which in turn leads to the end of that vision (charity).

The third instance of “Word and Spirit” occurs in The Great Code itself, where Frye writes that creative doubt of the Nietzschean variety can carry us “beyond the limits of dialectic itself, into the infinite identity of word and spirit that, we are told, rises from the body of death” (227). Words with Power is likewise relatively silent about the pairing of Word and Spirit. In that book Frye does write that “the unity of Word and Spirit in which all consciousness begins and ends” is what constitutes the spiritual self, and he speaks of the “intercommunication” of Word and Spirit (Words with Power, 251). In the Late Notebooks, however, the phrase “Word and Spirit” occurs some fifty-two times, often as “Word and Spirit dialogue” or “Word-Spirit dialogue.” Frye uses “dialogue” here in the sense of dialectic. And the dialectic is between the two major modes in Frye’s thought––the literary mode of the word writ large, or logos as Word, and the religious mode of spiritual vision, or pneuma as Spirit. But dialogue is also a metaphor for the relation between Word and Spirit, or an “intercommunication,” as in the passage just cited. The Word, Frye says in Notebook 27, gives substance to the Spirit. Each sets free the other, and they are united in one substance with the “Other.” That is, Word and Substance interpenetrate (CW 5, 9). “Infiltrate” is another word Frye uses to define the relation (CW 5, 272).