I wanted to respond a little more thoughtfully to Russell’s posts of the 28th and 30th. They demand some serious thought and a more considered response than what I offered in my previous post. I hope that this one may provoke further discussion.

Frye clearly believes that literature says something, and obviously he is in no way a formalist in the sense of believing that it is enough that a poem is beautifully made and so no more need be said about it. In Notebook 19 (one of the so-called 3rd book notebooks), Frye is struggling with the concept of the twin axes of speculation and concern, and makes the following note to himself:

Of course what I can present of this I must present not as my own speculation but as what I find implied by the order of words, as what poets say when they’re not saying anything. (my emphasis; CW 9: 32)

This defines what is of primary importance to Frye: what poets say when they’re not saying anything. This is right at the time when he is beginning to articulate the idea of literature as speaking the language of concern, and developing what later leads to the distinction between primary and secondary concerns. As he writes in The Critical Path:

Nobody would accept a conception of literature as a mere dictionary or grammar of symbols and images which tells us nothing in itself. Everyone deeply devoted to literature knows that it says something, and says something as a whole, not only in its individual works. In turning from formulated belief to imagination we get glimpses of a concern behind concern, of intuitions of human nature and destiny that have inspired the great religious and revolutionary movements of history. Precisely because its variety is infinite, literature suggests an encyclopaedic range of concern greater than any formulation of concern in religious or political myth can express. (103)

The phrase “concern behind concern,” of a concern that transcends the myth of concern, that transcends social mythology, is the germ of his later distinction between primary and secondary concerns.

That literature says something, and something of the utmost importance, is at the very heart of Frye’s theory of literature. This something that literature says is something very different from what it can very usefully tell you about a lot of other things, such as customs and rules of conduct, power relations, gender roles, prevalent beliefs and ideologies in a given historical period. These latter may indeed be a particular preoccupation of the author, and it may be difficult to separate an author’s anxieties or “secondary concerns” about race, sexuality, or class, for example, from his imaginative vision. It is precisely the job of criticism to make that separation, and to do so means the critic should have and show an awareness of all aspects of an author’s work. It is a murky job for criticism in the case of a writer like Celine or Sade–and there may indeed be writers where it just doesn’t seem possible or worth the candle.

Frye’s objection to giving a pre-eminent place to what we might, in a new sense, call “secondary criticism,” is that it introduces into the encounter with the literary work another source of anxiety, not the author’s but the critic’s. We hear of the “problematic” or the “dangerous” nature of certain aspects of a given work, as though we, or at least naive and less armored readers, had something to worry about, something to fear from the text, as if it could not be approached without the right protective gear. In Touching Feeling, Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick, one of the more sensible “celebrity critics,” as Russell calls them, has related this underlying fear of literature’s potential malevolence to what the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein has called the paranoid position. Paul Ricoeur has called the same stance the “hermeneutics of suspicion”: a prevalent attitude of distrust towards culture that is the legacy of Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud. These three, among others, contributed to a great paradigm shift in human thought, with enormous and revolutionary consequences, and they have rightly shaped the way we think about culture and literature. Frye has outlined the mythological significance of this shift in his discussion of the romantic revolution, for example, in Studies in Romanticism and chapter 7 of Words with Power.

The form it takes in New Historicism and cultural studies, however, verges at times on parody, and is perhaps a symptom of exhaustion in the paradigm itself. The critic adopts a supervisory attitude to the reader or student, who is assumed to have no critical judgment of her own. It is as if without expert help the untrained reader or student would be vulnerable and dangerously exposed to the bad ideology of the text. This is no doubt a useful posture when teaching communications and the subliminal techniques of advertising and media, but as a way of approaching literature it is woefully inadequate, at times even grotesque. Indeed, it ignores the much more potent critical perspective that only literature provides: the one that derives from what poets are saying when they aren’t saying anything.

I have to ask: are there really readers out there in any significant number who would find themselves infected with sexist attitudes by the reading of something like The Taming of the Shrew, or who might take Othello as an encouragement of abuse and violence against women? I have never met one, but if they exist they are in dire need of an education, not just of their way of thinking but perhaps most of all of their imaginations.

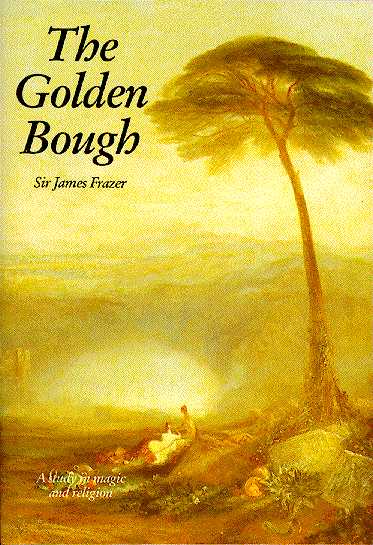

Erich Fromm wrote a book decades ago called The Forgotten Language. The title is a reference to the loss in Western culture of symbolic literacy, the ability to read anymore the archetypal language which is the lingua franca of dreams, fairytales and myths around the world. It is a commonplace now that general readers and students cannot be expected to have the common cultural grounding that would give them the ability to pick up on the significance of allusions and references to the Bible. But things are worse than that. The educating of undergraduates in the imaginative structures, conventions, and narrative shapes of literature is today not just neglected. It is actively opposed by a politicized criticism that sees in the myth and metaphor of literature little more than, to use Althusser‘s phrase, “a representation of the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence.”