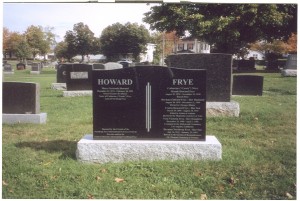

[The photo shows Cassie Frye’s headstone, which the Frye festival gathered funds for and saw to completion in 2004. Her burial place had been very poorly marked, something Frye observed with chagrin when he was here in the fall of 1990.]

Frye-centered activities at the Frye Festival, Moncton, New Brunswick

Note: Most of the early lectures are printed in a book I edited, “Verticals of Frye,” 2005.

Several lectures can be found here at the blog: click “Articles on NF” under “Journal.”

U-Tube has an interesting selection of Frye Festival lectures, conversations, and round tables.

The Frye Festival archive includes video cassettes of some lectures and round tables.

April, 2000 (year one of the festival)

Lecture: David Staines, “Northrop Frye and Canadian Culture”

Round Table: “The Regional Is the Real Source of the Poet’s Imagination”

Participants: Ann Copeland, Louise Desjardins, David Adams Richards, France Daigle, David Lonergan, George Elliott Clarke

Video: Northrop Frye’s Talk at the Université de Moncton, October, 1990. Introduced by Serge Morin

April, 2001

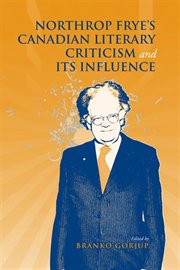

Lecture: Branko Gorjup, “Northrop Frye and His Canadian Critics”

Round Table: “The Way We See Nature and the Creative Imagination”

Participants: Sharon Butala, Gérald Leblanc, Alistair MacLeod,Louise Fiset, Daniel Paul, Emmanuel Adely

April, 2002

Lecture: Nella Cotrupi, “Process and Possibility: The Spiritual Vision of Northrop Frye”

Round Table: “Translation: Collaboration or Betrayal” (traduttore, traditore)

Participants: Alvin Lee, Francesca Valente, Antonio D’Alfonso, Jo-Anne Elder, Susanna Licheri, Robert Dickson

Discussion: “Remembering Frye”

Participants: Alvin Lee, Serge Morin, Francesca Valente, Robert Denham

Reading – Play: “Dear Norrie … Darling Helen” with Don Harron and Catherine McKinnon

April, 2003

Lecture: Robert Denham, “Moncton, Did You Know?”

Round Table: “From History to Fiction: When Fact Meets Fancy”

Participants: Bernhard Schlink, Zachary Richard, Ursula Hegi, Roberto Mann, Joyce Hackett, Lise Bissonnette

Round Table with Moderator John Ralson Saul: “Mythology and National Identity”

Participants: Bernhard Schlink, Fance Daigle, André Roy, Joyce Hackett, Naïm Kattan

Northrop Frye Conference with Naïm Kattan: “La réception de l’oeuvre de Northrop Frye dans la Francophonie” (“Frye’s Reception in the French-Speaking World”)

Conference Round Table: “History, Myth, and the Concept of Truth in Northrop Frye”

Participants: Naïm Kattan, Robert Denham, Ross Leckie, Serge Morin

April, 2004

Lecture: John Ayre, “Into the Labyrinth: Northrop Frye’s Personal Mythology”

Round Table: “Imagining Other Times, Other Places: Fiction and Historical Accuracy”

Participants: Alan Cumyn, Claude Le Bouthillier, Simone Poirier-Bures, Alain Dubos, Douglas Glover, Madeleine Gagnon

Northrop Frye Conference with Michael Dolzani: “The View from the Northern Farm: Northrop Frye and Nature”

Conference Round Table: “There Are No Gods in Nature: Frye’s Spiritual Vision of Nature”

Participants: Michael Dolzani, Joe Velaidum, Jean O’Grady, Paul Curtis

Conference Lecture: Robert Denham, “Northrop Frye and Medicine”

Tribute to Robert Denham: With Guest Speaker Alvin Lee

Video: Northrop Frye’s Talk at the Université de Moncton, October, 1990. Introduced by Serge Morin

November, 2004

Unveiling of the Cassie Frye Headstone in Moncton’s Elmwood Cemetery A joint project of the Frye Festival and Friends of the Festival Poetry readings by Alan Cooper and Hélène Harbec

April, 2005

Lecture: B. W. Powe, “Northrop Frye and Marshall McLuhan: Northern Mystics”

Round Table: “What Is the Most Difficult Subject to Write About?”

Participants: Russell Smith, Jacques Savoie, Nikki Gemmell, Catherine Cusset, Louise Bernice Halfe, J. Roger Léveillé

Round Table: “The Oral / Written Tension in Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Cultures”

Participants: Elisapie Isaac, Witi Ihimaera, Gérald Leblanc, Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm, Yves Sioui-Durand

Northrop Frye Conference with Alvin Lee: “What The Great Code Is and Does”

Conference Round Table: “Myth and Identity: The Role of Myth in Forming a Sense of Identity”

Participants: Glen R. Gill, Yves Sioui-Durand, Jean O’Grady, Maurizio Gatti

Video: Northrop Frye’s Talk at the Université de Moncton, October, 1990. Introduced by Serge Morin

April, 2006

The Antonine Maillet – Northrop Frye Lecture: Neil Bissoondath, “The Age of Confession”

Round Table: “Is There a Future for Poetry?”

Participants: Nadine Fidji, Wesley McNair, Huguette Bourgeois, Wendy Morton, Roméo Savoie, Kwame Dawes

Round Table: “Let My People Go: The Power of Myth, with Special Reference to the Myth of Deliverance”

Participants: Jeffery Donaldson, Patrick Chamoiseau, André Alexis, Michel Tétu

Round Table: “History: A Burden or a Gift?”

Participants: Patrick Chamoiseau, Zakes Mda, Monique Ilboudo, George Elliott Clarke, Gil Courtemance

Play, with Peter Yan and Frank Adriano: “Northrop Frye High: A Play Remembering Frye”

April, 2007

The Antonine Maillet – Northrop Frye Lecture: David Adams Richards, “Playing the Inside Out”

Round Table: “Ways of Understanding Popular Culture”

Participants: Brecken Rose Hancock, Serge Morin, Tony Tremblay

Round Table: “The Graphic Novel Grows Up”

Participants: Bernice Eisensteir, Dano LeBlanc, Harvey Pekar, Michel Rabagliati

Frye Symposium Lecture: Jean O’Grady, “Revaluing Values”

Frye Symposium Lecture: Robert Denham, “Frye’s Magnum Opus: Fifty Years After”

Tribute to Jean O’Grady: With Guest Speaker Bob Denham

April, 2008

The Antonine Maillet – Northrop Frye Lecture: Alberto Manguel, “Why Homer Must Be Blind”

Dialogue: Nancy Huston in Conversation with Alberto Manguel

Frye Symposium Lecture: Glenna Sloan, “Northrop Frye Applied to the Classroom”

Symposium Round Table: “The Eros of Reading: Why Do Some Students Fall in Love with Reading and Others Don’t”

Participants: Glenna Sloan, Peter Sanger, J. Andrew Wainwright

April, 2009

The Antonine Maillet – Northrop Frye Lecture: Monique LaRue, “Entre deux romans: le temps de l’écrivain” (“Between Two Books: The Writer’s Time”)

10th Anniversary Celebrations: A conversation between John Ralston Saul and Antonine Maillet

Lecture: John Ralston Saul, “A Fair Country: Telling Truths about Canada”

Frye Symposium Lecture: Germaine Warkentin, “Poetry and the Writing Life”

Symposium Round Table: “How Might The Educated Imagination Lead Us Into the 21st Century?”

Participants: Jean Wilson, Serge Patrice Thibodeau, Germaine Warkentin, Serge Morin

April, 2010

The Antonine Maillet – Northrop Frye Lecture: Noah Richler, “What We Talk About When We Talk About War”

Frye Symposium Lecture: Craig Stephenson, “Reading Frye Reading Jung”

Symposium Round Table: “Voyaging into the Unknown in Folk Tales and in Dreams”

Participants: Craig Stephenson, Kay Stone, André Lemelin, Ronald Labelle

April, 2011

The Antonine Maillet – Northrop Frye Lecture: Margaret Atwood, “Mythology and Me: The Late 1950s at Victoria College”

Round Table: “New Technology and the Changing Face of Reading”

Participants: Michael Happy, Daniel Dugas, B. W. Powe, Serge Patrice Thibodeau

Pop & Frye: Michael Happy, “Frye for Beginners”

Frye Symposium Lecture: B. W. Powe, “Visions of Marshall McLuhan and Northrop Frye: Lecture in Honour of Marshall McLuhan’s 100th Birthday”

April, 2012

The Antonine Maillet – Northrop Frye Lecture: Antonine Maillet, L’écrivain, ce farfouilleur des fonds de tiroirs de l’imaginaire.” (“The Writer : Rummager in the Stuff at the Bottom of the Drawer of the Imagination”)

Round Table: “Culture and the Critic”

Participants: Terry Fallis, John Doyle, David Gilmour, Nora Young

Play / Conversation: “Temps perdu in the Maple Leaf Lounge” A live conversation betweenMarshall McLuhan and Northrop Frye, as played by Marshall Button and Sandy Burnett

Frye Centenary Lecture: Ian Balfour, “Northrop Frye Beyond Belief”

Launch: Special edition of ellipse magazine, marking Frye’s centenary

July, 2012

Centenary Celebration: Unveiling of a bronze statue of Northrop Frye, seated on a bench in front of the Moncton Public Library. Darren Byers and Fred Harrison, artists, in collaboration with Janet Fotheringham.

Centenary Celebration: Announcement of the Robert D. Denham donation to the Moncton

Public Library, with speeches by various city and provincial officials, and by Robert Denham himself.

[

[