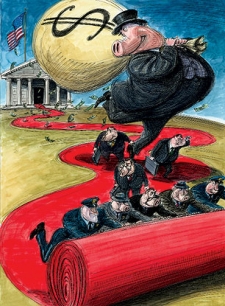

Here’s a nice supplement to my earlier post from Matt Taibbi’s article, “Why Isn’t Wall Street in Jail?” in this week’s Rolling Stone:

“Here’s how regulation of Wall Street is supposed to work. To begin with, there’s a semigigantic list of public and quasi-public agencies ostensibly keeping their eyes on the economy, a dense alphabet soup of banking, insurance, S&L, securities and commodities regulators like the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), as well as supposedly “self-regulating organizations” like the New York Stock Exchange. All of these outfits, by law, can at least begin the process of catching and investigating financial criminals, though none of them has prosecutorial power.

The major federal agency on the Wall Street beat is the Securities and Exchange Commission. The SEC watches for violations like insider trading, and also deals with so-called “disclosure violations” — i.e., making sure that all the financial information that publicly traded companies are required to make public actually jibes with reality. But the SEC doesn’t have prosecutorial power either, so in practice, when it looks like someone needs to go to jail, they refer the case to the Justice Department. And since the vast majority of crimes in the financial services industry take place in Lower Manhattan, cases referred by the SEC often end up in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York. Thus, the two top cops on Wall Street are generally considered to be that U.S. attorney — a job that has been held by thunderous prosecutorial personae like Robert Morgenthau and Rudy Giuliani — and the SEC’s director of enforcement.

The relationship between the SEC and the DOJ is necessarily close, even symbiotic. Since financial crime-fighting requires a high degree of financial expertise — and since the typical drug-and-terrorism-obsessed FBI agent can’t balance his own checkbook, let alone tell a synthetic CDO from a credit default swap — the Justice Department ends up leaning heavily on the SEC’s army of 1,100 number-crunching investigators to make their cases. In theory, it’s a well-oiled, tag-team affair: Billionaire Wall Street Asshole commits fraud, the NYSE catches on and tips off the SEC, the SEC works the case and delivers it to Justice, and Justice perp-walks the Asshole out of Nobu, into a Crown Victoria and off to 36 months of push-ups, license-plate making and Salisbury steak.

That’s the way it’s supposed to work. But a veritable mountain of evidence indicates that when it comes to Wall Street, the justice system not only sucks at punishing financial criminals, it has actually evolved into a highly effective mechanism for protecting financial criminals. This institutional reality has absolutely nothing to do with politics or ideology — it takes place no matter who’s in office or which party’s in power. To understand how the machinery functions, you have to start back at least a decade ago, as case after case of financial malfeasance was pursued too slowly or not at all, fumbled by a government bureaucracy that too often is on a first-name basis with its targets. Indeed, the shocking pattern of nonenforcement with regard to Wall Street is so deeply ingrained in Washington that it raises a profound and difficult question about the very nature of our society: whether we have created a class of people whose misdeeds are no longer perceived as crimes, almost no matter what those misdeeds are. The SEC and the Justice Department have evolved into a bizarre species of social surgeon serving this nonjailable class, expert not at administering punishment and justice, but at finding and removing criminal responsibility from the bodies of the accused.

The systematic lack of regulation has left even the country’s top regulators frustrated. Lynn Turner, a former chief accountant for the SEC, laughs darkly at the idea that the criminal justice system is broken when it comes to Wall Street. ‘I think you’ve got a wrong assumption — that we even have a law-enforcement agency when it comes to Wall Street,’ he says.”

(Illustration by Victor Juhasz)