There’s a silly essay by Graham Greene about H[enry] J[ames]’s view of Catholicism which is only about GG’s own obsessions: if there’s one thing HJ could do, it was separate a social institution from the essential proclamation it purported to carry. He wouldn’t head for any god-damned ‘fold’ on his deathbed, like Wallace Stevens. (Notebooks on Romance 356-57)

Greene’s essay “Henry James: The Religious Aspect” may approach James at rather an oblique angle, but I don’t think “silly” is really a fair description. Edwin Fussell has written a whole book on The Catholic Side of Henry James, where he says that “Henry James is far more Catholic in print than there is any evidence for his ever having been in his private life.” Fussell goes to work in a much more thorough way and scholarly way, but he is essentially building on Greene’s insights in order to provide an insightful and unexpected perspective on the Master. Greene’s characteristic obsessions enabled him to identify a pattern of references to Catholicism in James, which he related to what he called in another essay on James “a sense of evil religious in its intensity” (“Henry James: The Private Universe”). Interestingly, Frye says something similar in the same notebook in which he condemns Greene’s essay. Frye comments that a sense of evil is lacking in Jane Austen: “while she knows what evil is, she deliberately excludes it; HJ has a sense of evil comparable to Balzac’s or Dostoievsky’s, and can’t exclude it. It leaks through the walls constantly” (NR 353). The comparison between James and Dostoyevsky also can be found in Greene’s essay. With reference to the recent discussion of Frye and Harold Bloom, it’s worth pointing out that Bloom calls Greene’s essay on James “egregious” and ridicules him for comparing James and Dostoyevsky!

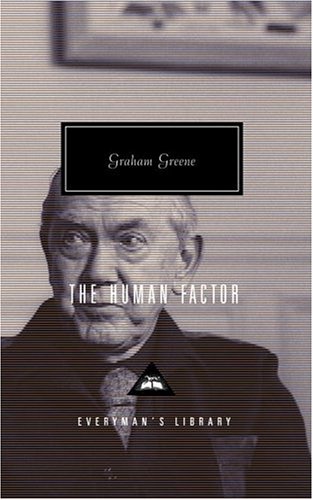

For me, there is a stranger moment in Greene’s criticism of James, and one more revealing of Greene’s own anxieties, when he writes in a third essay that “what deeply interested him, what was indeed his ruling passion, was the idea of treachery, the ‘Judas complex’” (“The Portrait of a Lady”). That statement would in fact serve as a good starting point for an overview of Greene’s fiction. From his first historical novel, The Man Within (1929), to the late political novels The Honorary Consul (1973) and The Human Factor (1978), betrayal is a major motif in Greene’s novels, and memories of his own troubled schooldays at Berkhamsted School, where his father was the headmaster, crop up everywhere. Greene is a novelist of obsessions – David Lodge once catalogued an impressive list of them, including dreams and dentistry – and therefore it is not surprising that his criticism is also obsessive in nature. Like the criticism of many writers, it often does illuminate his own fiction more than the ostensible subject, but in the case of Henry James he does have something to say worth listening to. In a future post I will say something about Greene on Shakespeare, in the context of Frye’s comments on ideological criticism; there is also much more to say about Frye and James, and I hope to return to that topic as well.