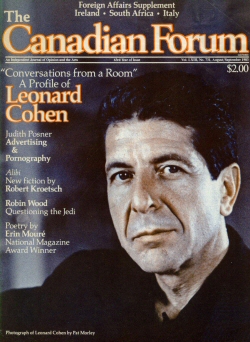

Below are the four complete Christmas editorials Russell Perkin refers to in his article, “Northrop Frye on Christmas,” newly posted in our Journal (see the live link in the upper right hand corner of our Widgets menu).

MERRY CHRISTMAS (I)

December 1946

Canadian Forum, 26 (December 1946): 195. Reprinted in RW, 378–9, and in Northrop Frye on Religion.

Christmas is far, far older than Christianity, as even the pre-Christian Yule and Saturnalia were late developments of it, and it was never completely assimilated to the Christian faith. Our very complaints about the hypocritical commercializing of the Christmas spirit prove that, for they show how vigorously Christmas can flourish without the smallest admixture of anything that could reasonably be called Christian. Christmas is the tribute man pays to the winter solstice, and perhaps to something in himself of which the winter solstice reminds him. We turn on all our lights, and stuff ourselves, and exchange presents, because our ancestors in the forest, watching the sun grow fainter until it was a cold weak light unable to bring any more life from the earth, chose the shortest day of the year to defy an almost triumphant darkness and declare their loyalty to an almost beaten sun. We have learned that we do not need to worry about the sun, and that there is no monster big enough to swallow it. We have yet to learn that no atomic bomb will ever destroy the human race, that no Dark Age will (as it never has done) totally overspread the earth, that no matter how often man is knocked down, he will always pick himself up, punch drunk and sick and morbidly aware of his open guard, spit out some more teeth, and start slugging again. At that point there is a division between those for whom Christmas is a religious festival, and for whom the new light coming into the world must be divine as well as human if the struggle is ever to be won, and those for whom the festival is human and natural and points to an ultimate human triumph. With this difference in outlook the Canadian Forum has nothing to do, but to all of its readers who recognize the primary meaning of Christmas, and who realize that generosity and hospitality and the sharing of goods make a better world than misery and persecution and the cutting of throats, it wishes a Merry Christmas.

MERRY CHRISTMAS?

December 1947

Canadian Forum, 27 (December 1947): 195. Reprinted in RW, 380–1, and in Northrop Frye on Religion.

A passage in the Christmas Carol describes how Scrooge saw the air filled with fettered spirits, whose punishment it was to see the misery of others and to be unable to help. One hardly needs to be a ghost to be in their position, and as we light the fires for our Christmas they throw into the cold and darkness outside the wavering shadows of ourselves, unable to break the deadlock of the U.N., unable to stop the slaughter in China or India or the terror in Palestine, unable to release the victims of tyrannies still undestroyed, unable to deflect the hysterical panic urging us to war again, unable to do anything for the vast numbers who will starve and freeze this winter, and above all unable to break the spell of malignant fear that holds the world in its grip. Yet Dickens’ ghosts were punished for having denied Christmas, and we can offset our helplessness by affirming Christmas, by returning once more to the symbol of what human life should be, a society raised by kindliness into a community of continuous joy.

Because the winter solstice festival is not confined to Christianity, it represents something that Christians and non-Christians can affirm in common. Christmas reminds us, whether we put the symbol into religious terms or secular ones, that there is now in the world a power of life which is both the perfect form of human effort and all we know of God, and which it is our privilege to work with as it spreads from race to race, from nation to nation, from class to class, until there is no one shut out from the great invisible communion of the Christmas feast. Then the wish of a Merry Christmas, which we now extend to all our readers, will become, like the wish of a fairy tale, a worker of miracles.