From Barker Fairley: Portraits (Toronto: Methuen, 1981): 48–9

Further on Barker Fairley and the refusal of U.S. customs to grant him a visa to lecture on Goethe at Bryn Mawr because of his leftist sympathies (he had supported a Soviet friendship organization), these passages from Frye’s Diaries:

“Poor old Barker still feels pretty blue: he was just beginning to start exploring U.S.A. & get some real recognition when they slammed the door on him & he has to pick up a trip to England as consolation prize, & of course he knows all about England.” (20 March 1950)

“Barker [Fairley] is taking the C.P.R. [Canadian Pacific Railway] train to St. John that goes across Maine, so he says he’ll have a chance to piss on the United States. Just the same Barker has been deeply hurt by his exclusion. I wish the Americans didn’t do all the silly things the Communists expect them to do and know in advance how to take advantage of.” (9 April 1950)

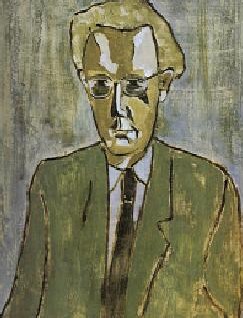

The lectures that Fairley was to give at Bryn Mawr were later published as Goethe’s Faust: Six Essays (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1953). Fairley incidentally painted Frye’s portrait in 1969, which is reproduced above.

About his subject, Fairley has this to say:

I first ran into the name of Northrop Frye when, returning to Canada in 1936, I read an article by him in The Canadian Forum about that delightful dance troupe “The Ballet Joos.” They acted, or rather danced, scenes from social life. I remember particularly “The City,” which conveyed both gregariousness and loneliness and gave me a pleasure greater than any I got from classical dancing. Does he remember this too with the same vivid pleasure, I wonder?

He now switches my mind back to the University of Toronto as it was then. It seemed to me in those days that University College with its undenominational freedom was carrying the torch of the humanities ahead of the other colleges. This was a pardonable illusion, which any of the four colleges was entitled to. But what with Northrop Frye and his mastery of the whole field of literature as we know it and his colleague, Kathleen Coburn, with her command of the Coleridge battalion — to say nothing of her very special autobiography In Pursuit of Coleridge — it appears now that I was wrong and that Victoria is in the lead as taking the University’s name more effectively abroad than I ever expected.

My portrait of Northrop Frye is a third attempt after two ignominious failures. I was with Aba Bayefsky the first time. He succeeded — more than succeeded — and I collapsed. After a second collapse I said, “Norrie, let me try again.” He agreed. And sure enough, that inscrutable face of his yielded at last, and his gentle nature came through to my great delight.