G. Wilson Knight (1897-1985) was professor of English at Trinity College, University of Toronto, in the 1930s; he returned to Britain in 1941, where he taught at the University of Leeds until 1962; his main interest was Shakespeare, many of whose plays he produced and acted in; his best‑known book, Wheel of Fire, was published in 1930. What follows are the references to Knight in Frye’s writing:

1. There’s a series of New Directions studies on “Makers of Modern Literature,” by Harry Levin on Joyce, very well reviewed, & now one by David Daiches on Woolf, said to be not so good. Wilson Knight is producing another book, this time on Milton.[1] A new Simenon translated, two stories again. He’s so good that his stories don’t even depend for their interest on the puzzle. [Diaries]

2. Well, Crane’s third lecture was a little easier to follow: more names and historical connections. But his relativism and pluralism are breaking down into an Aristotle (and Crane) contra mundum attitude. Everybody’s in the other camp—the camp where poetry is treated as a form of discourse. Now I’ve lost Aristotle: I don’t understand how he’s distinguishable from this. Anyway, the discourse people include the Latin rhetoricians, the medieval people, the critics of the Renaissance who thought they were Aristotelians but weren’t, the romantics, and the romantic tradition extending to the new critics & the myth critics. The last group includes Edmund Wilson, Lionel Trilling, Francis Ferguson, Wilson Knight, and me. [Diaries]

3. King Lear attempts to achieve heroic dignity through his position as a king and father, and finds it instead in his suffering humanity: hence it is in King Lear that we find what has been called the “comedy of the grotesque,”[2] the ironic parody of the tragic situation, most elaborately developed. [Anatomy of Criticism, 237]

4. But he was quickly bored if the conversation ran down in gossip or trivialities. The personnel at his parties naturally changed over the course of years, but from Bertram Brooker and Wilson Knight in the 1930s to Marshall McLuhan and Douglas Grant in the 1960s, he never wavered in his affection for friends who could talk, and talk with spirit, content, and something to say. [“Ned Pratt: The Personal Legend”]

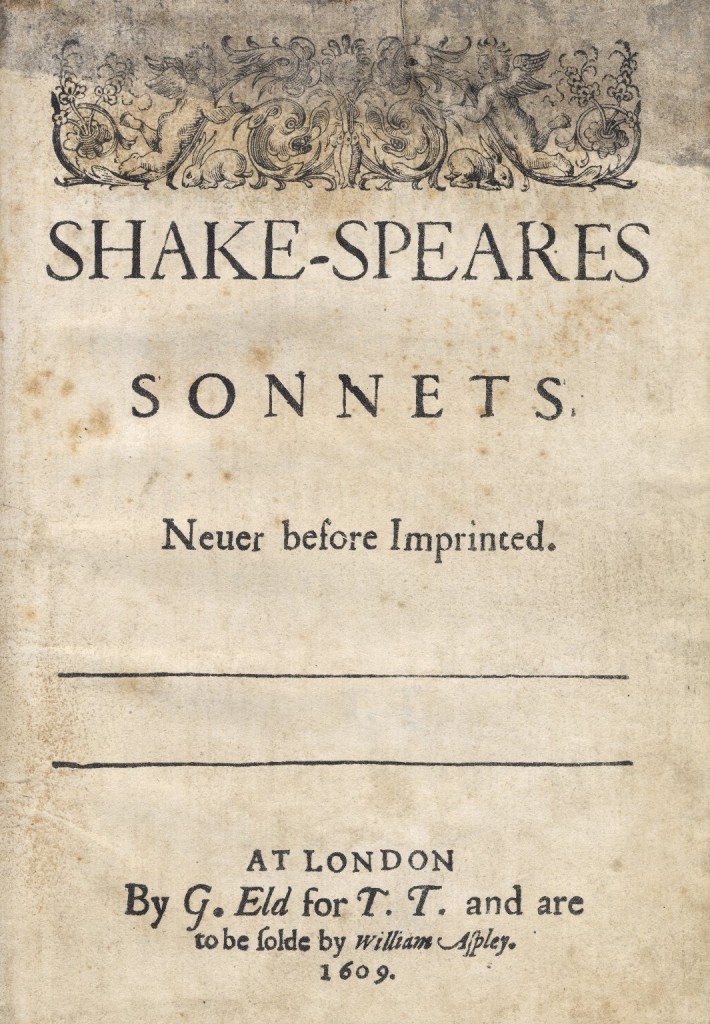

5. There were many little magazines and attempts at experimental theatre (I can’t answer for the dance groups, of which as I remember there were several), but they fought hard and died quickly—all but the unique and miraculous Canadian Forum, which a dozen university staff members, then as now, worked hard to keep going and up to standard. A few rumours also seeped through from other colleges, of how Wilson Knight at Trinity had revolutionized the study of Shakespeare, of how Gilbert Norwood had written of Classical drama with a sophisticated knowledge of the modern stage, of Charles Cochrane’s mighty struggle with Christianity and Classical Culture. [“Autopsy of a Old Grad’s Grievance,” in Northrop Frye on Education]

6. Surrey, however, established a new pentameter line for his century. Its prestige captured Spenser, who had begun with accentual experiments and contrapuntal singing-matches, but for his epic moved away from musical rhythms, as Milton moved toward them. Shakespeare, however, and most Elizabethan drama with him, grew steadily swifter in movement, breaking out of the line into galloping recitativos, with the diction becoming sharper and more dissonant, the imagery grimmer and more sombre, the thought more tangled and obscure—in short, more musical in every way. The use of music by Shakespeare, however, is outside our scope: his musical accompaniments and imagery have been dealt with, notably by Granville Barker and Wilson Knight, but such features as the contrapuntal construction of King Lear have yet to be analysed. [“Music in Poetry”]

7. This inductive movement towards the archetype is a process of backing up, as it were, from structural analysis, as we back up from a painting if we want to see composition instead of brushwork. In the foreground of the grave-digger scene in Hamlet, for instance, is an intricate verbal texture, ranging from the puns of the first clown to the danse macabre of the Yorick soliloquy, which we study in the printed text. One step back, and we are in the Wilson Knight and Spurgeon group of critics, listening to the steady rain of images of corruption and decay. [“Archetypes of Literature”]

8. The inductive studies of the recurring imagery of King Lear by Wilson Knight and Caroline Spurgeon have, for me at least, gone a long way to illuminate this meaning, and I think a careful comparison of the different contexts in which such words as “nature” and “nothing” appear would do a good deal more. [Review of Critics and Criticism]