I’ve been reminded this weekend not to post too quickly and not to post angry. I did both with my review of Matt Taibbi’s Griftopia. I’ve therefore gone back, cleaned it up, added some links to provide more context, and expanded the last four paragraphs.

I’m making my way through Matt Taibbi’s Griftopia: Bubble Machines, Vampire Squids and the Long Con That Is Breaking America. It provides documentation for the worst case scenario that is increasingly becoming the new normal: the rise of plutocracy with government acting as a conduit to accelerate the transfer of wealth upward.

Most people probably know that the middle class share of wealth has been flat-lined for thirty years, coinciding with the ascendancy of Thatcherism, Reaganomics, deregulation, de-unionization, and trickle-down economics (which does not result in the trickling down of wealth but is startlingly efficient at making the rich richer and the poor poorer). But most people probably do not know that the top 1% of the population in the U.S. owned 34% of the nation’s wealth at the time of the collapse of the financial market in 2008, or that it now owns 38%. Which is to say that the wealthiest class of people in whose interests the market crashed two years ago have, as a result, increased pretty substantially their already disproportionate share of wealth.

Many will no doubt reflexively cite the principles of market economy to rationalize this. But there’s no market economy at work here. As we saw with the bailouts of Wall Street, being on the wrong side of moral hazard is for suckers. The destructive part of creative destruction is reserved for losers. Those who belong to the “too big to fail” class, meanwhile, have nothing to worry about. When they fail they get bail, and they know it. It’s too bad the Teabaggers — the incoherent mob organized and funded by the most thuggish of Wall Street interests — don’t know, as Taibbi puts it, who they should be aiming their pitchforks at.

Taibbi lays out the story with a pugnacious style. Surviving as a reporter in Vladimir Putin’s Moscow has left him in no mood for high-end gangsterism: he’s the guy who coined the often repeated description of Goldman Sachs as a “vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity.”

In the excerpt below, for example, Taibbi describes the decades-long genesis of the ’08 disaster under the palsied hand of the ideologically blinkered Randian, Alan Greenspan. During the Internet bubble of the mid-1990s — when out-of-nowhere tech companies with no assets were exploding in value by up to 400% overnight — Greenspan, as head of the Federal Reserve, did nothing to rein in what he’d only timidly (and only once) referred to as the “irrational exuberance” of the markets:

According to Greenspan, these companies were not necessarily valued incorrectly. All that was needed to make this make sense was to rethink one’s conception of “value.” As he put it during the boom: “[There is] an ever-increasing conceptualization of our Gross Domestic Product — the substitution, in effect, of ideas for physical value.”

What Greenspan was saying, in other words, was that there was absolutely nothing wrong with bidding up to $100 million in share value some hot-air Internet stock, because the lack of that company’s “physical value” (i.e., the actual money those three employees weren’t earning) could be overcome by the inherent value of their “ideas.”

To say that this was a radical reinterpretation of the entire science of economics is an understatement — economists had never dared measure “value” except in terms of actual concrete production. It was equivalent to a chemist saying that concrete becomes gold when you paint in yellow. It was lunacy. (61-2)

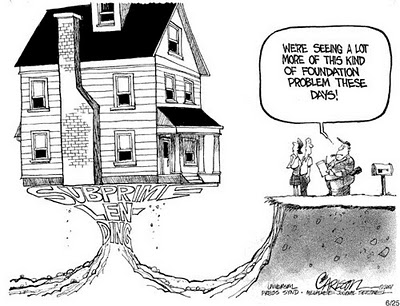

When the tech bubble finally burst in the spring of 2000, Greenspan, under unrelenting pressure from financial institutions, engineered the real estate bubble that nearly threw the entire world into a Depression of terrifying proportions:

Looking back now at the early years in the 2000s, Greenspan’s comments almost seem like the ravings of a madman. The nation’s top financial official began openly encouraging citizens to use the equity in their homes as an ATM. “Low rates have also encouraged households to take on larger mortgages when refinancing their homes,” he said. “Drawing on home equity in this manner is a significant source of funding for consumption and home modernization.”

But he went really crazy in 2004, when he told America that adjustable-rate mortgages were a good product and safer, fixed-rate mortgages were unattractive. (71)

When this bubble burst and the financial market that supported it collapsed in the fall of 2008, millions of people were stripped of their remaining wealth and millions more lost their jobs and the security their labor ought to have earned them. All of this happened in the context of Greenspan keeping interest rates low and flooding the market with cash for the benefit of Wall Street and at the cost of middle class families who had previously prepared for their future with government bonds and interest on their savings. But because interest rates were so low, these traditional and secure sources of investment were virtually worthless. People of relatively modest means, therefore, were driven into what was by then a dangerously predatory market because they had few alternatives. What too many of them ended up with were adjustable-rate mortgages, which made sense at a time when interest rates had been steadily declining for years and the real estate bubble had pushed the value of property steadily upward.

Note, however, that Greenspan very sharply increased interest rates at the end of his tenure at the Federal Reserve in 2006 to ensure a greater return on variable-rate mortages to the brokers, banks and financial institutions who had issued them. When those rates went up, people could no longer afford to pay and fell into foreclosure in what was at that point an up and down the line fraud. Add to this the unregulated derivatives market and its non-capitalized “insurance” against risk, and the whole thing became a monstrous rat king of a clusterfuck by people who are obscenely well-compensated to know better. Because they didn’t know better — or, perhaps more precisely, pretended they didn’t — the market was flooded with toxic assets by way of financial instruments like “credit default swaps,” which were divided up into small packets with AAA ratings and thrown into otherwise healthy portfolios. These toxic assets infected the entire system like a retrovirus until financial institutions that were leveraged beyond their ability to meet their obligations began to collapse. Legendary institutions like Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers, AIG, and Merrill Lynch failed or were sold for pennies on the dollar, triggering the Great Recession and the mass unemployment of those who could least afford to absorb it. Those responsible, meanwhile, received hundreds of billions of dollars in bailout money, and before very long were finding reasons to give one another bonuses amounting to billions.

That’s why Taibbi has coined the term “grifter class,” which includes Wall Street and its one reliable patron with very deep pockets: a government that governs only for the benefit of an already wealthy elite on the principle that what is good for Wall Street is good for Main Street. And that’s the grift, with no end of it in sight. Don’t count on the Teabaggers to get it or on Fox News to report it.

And, of course, this is not just an American problem. With the collapse of banks and economies and the rise of unsustainable unemployment in Europe, this is clearly everybody’s problem. The angry initial Chinese response was to suggest that, because of American irresponsibility, the world ought to be thinking about replacing the dollar as a reserve currency. That probably won’t happen, but the fact that it was suggested at all by one of the newest economic superpowers indicates just how much things have changed. If it were to happen, however, the Americans would be stuck with an already staggering debt which could no longer be repaid with their own currency. The consequences of that are unthinkable. Which is why we’ve got to think about them.