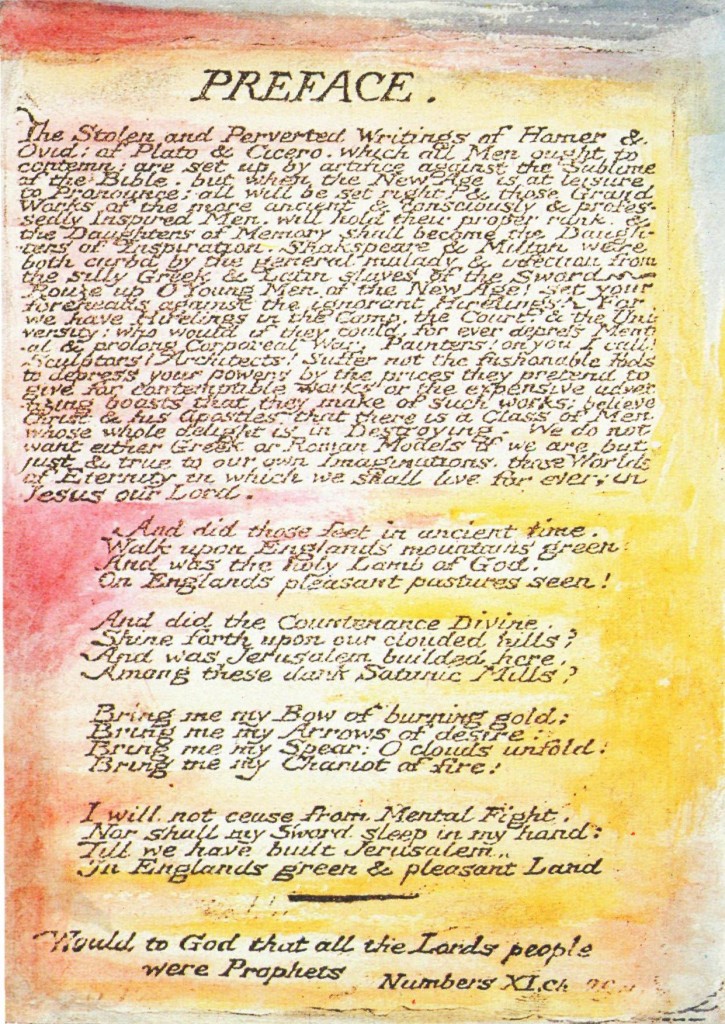

The Preface to Blake’s Milton

James Pollock’s new poem about the young Norrie in the latest issue of Agni here.

“I have had sudden visions.”

Bloor Street, Toronto, 1934

3 a.m. in the all-night diner, dizzy

with Benzedrine and lack of sleep, old books

and papers scattered across the table.

With his pen, his Dickensian spectacles,

his pounding, driving Bourgeois intellect,

he charges into a poem by William Blake

with two facts and a thesis, cuts Milton

open on the table like a murdered corpse

and spins it like a teetotum until

he’s put each sentence through its purgatory

and made the poet bless him with a sign:

thus (though perhaps one can picture this

only from a point outside of time)

he sees the shattered universe around him

explode in reverse, and make the flying

shards of its blue Rose window whole again.