Frye in The Secular Scripture: “popular literature […] is neither better nor worse than elite literature, nor is it really a different kind of literature.” (CW 18, 23)

Daily Archives: November 30, 2010

Frye and Popular Art Forms

Further to yesterday’s comments on “Huxley and Orwell: Two Varieties of Dystopia”

Frye was always open to what he called “naïve” artistic forms—by which he meant primitive and popular. These included cartoons. In the Anatomy he writes:

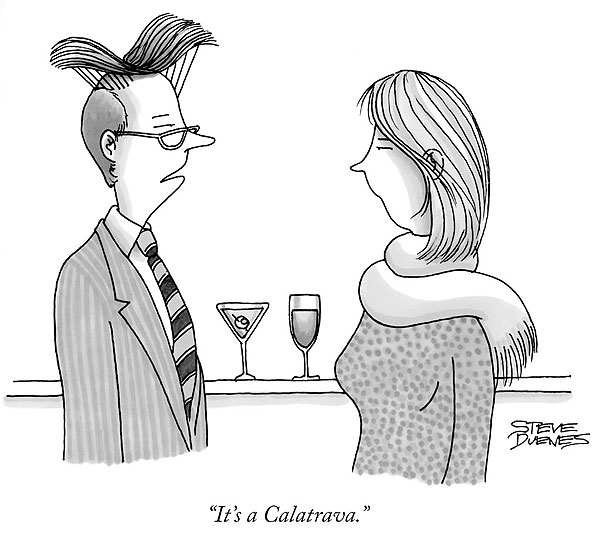

The apparatus of ‘mass media’ and ‘audiovisual aids’ plays a similar allegorical role in contemporary education. Because of this basis in spectacle, naive allegory has its centre of gravity in the pictorial arts, and is most successful as art when recognized to be a form of occasional wit, as it is in the political cartoon.” And later, in his account of the pictorial thrust of the lyric, he says, “In such emblems as Herbert’s ‘The Altar’ and ‘Easter Wings,’ where the pictorial shape of the subject is suggested in the shape of the lines of the poem, we begin to approach the pictorial boundary of the lyric. The absorption of words by pictures, corresponding to the madrigal’s absorption of words by music, is picture-writing, of the kind most familiar to us in comic strips, captioned cartoons, posters, and other emblematic forms. A further stage of absorption is represented by Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress and similar narrative sequences of pictures, in the scroll pictures of the Orient, or in the novels in woodcuts that occasionally appear.

Frye’s work is replete with references to cartoons and comic strips. The New Yorker is his favourite source of the former, and from time to time he mentions cartoonists by name: David Low, Hugh Niblock, Saul Steinberg.

Otherwise, from the Anatomy:

The earliest extant European comedy, Aristophanes’ The Acharnians, contains the miles gloriosus or military braggart who is still going strong in Chaplin’s Great Dictator; the Joxer Daly of O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock has the same character and dramatic function as the parasites of twenty-five hundred years ago, and the audiences of vaudeville, comic strips, and television programs still laugh at the jokes that were declared to be outworn at the opening of The Frogs.

The principle of repetition as the basis of humour both in Jonson’s sense and in ours is well known to the creators of comic strips, in which a character is established as a parasite, a glutton (often confined to one dish), or a shrew, and who begins to be funny after the point has been made every day for several months.

The essential element of plot in romance is adventure, which means that romance is naturally a sequential and processional form, hence we know it better from fiction than from drama. At its most naive it is an endless form in which a central character who never develops or ages goes through one adventure after another until the author himself collapses. We see this form in comic strips, where the central characters persist for years in a state of refrigerated deathlessness.

Humour, like attack, is founded on convention. The world of humour is a rigidly stylized world in which generous Scotchmen, obedient wives, beloved mothers-in-law, and professors with presence of mind are not permitted to exist. All humour demands agreement that certain things, such as a picture of a wife beating her husband in a comic strip, are conventionally funny. To introduce a comic strip in which a husband beats his wife would distress the reader, because it would mean learning a new convention.

Jonathan Swift

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3o2sfM05O4U

“A Description of the Morning”

Today is Jonathan Swift‘s birthday (1667-1745)

Frye in “The Imaginative and the Imaginary”:

The eighteenth century was the period in which this view of the imagination struggled with, and was finally defeated by, an opposed conception which came to power in the Romantic movement. At the beginning of the century we have Swift, for whom established authority in church and state was the only thing in human life strong enough to restrain the desperately irrational soul of man. In his day the conception of “melancholy” was out of fashion, but another ancient medical notion of “spirits” or “vapours” rising from the loins into the head was still going strong. For Swift, or at least for the purposes of Swift’s satire, all behavior that breaks down society is caused by an uprush either of digestive disturbances or of sexual excitement into the head. Swift’s chief target is the left-wing Protestantism which in the seventeenth century had carried religious melancholy to the point of replacing the authority of the church with private judgment and had made a virtue even of political rebellion. But he finds the same phenomena in the political tyrant who substitutes his own will for the social contract, or the poet who allows his emotions to take precedence over communication. “The very same principle,” he says, “that influences a bully to break the windows of a whore who has jilted him, naturally stirs up a great prince to raise mighty armies, and dream of nothing but sieges, battles and victories.” (CW 21, 430)