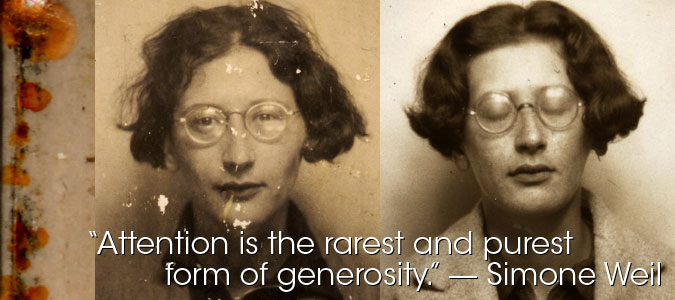

Today is Simone Weil‘s birthday (1909-1943).

From The Great Code:

In our day Simone Weil has found the traditional doctrine of the Church as the Body of Christ a major obstacle — not impossibly the major obstacle — to her entering it. She points out that it does not differ enough from other metaphors of integration, such as the class solidarity metaphor of Marxism, and says:

“Our true dignity is not to be parts of a body. . . . It consists in this, that in the state of perfection which is the vocation of each one of us, we no longer live in ourselves, but Christ lives in us; so that through our perfection . . . becomes in a sense each one of us, as he is completely in each host. The hosts are not a part of his body.”

I quote this because, whether she is right or wrong, and whatever the theological implications, the issue she raises is a central one in metaphorical vision, or the application of metaphors to human experience. We are born, we said, within the pre-existing social contract out of which we develop what individuality we have, and the interests of that society take priority over the interests of the individual. Many religions, on the other hand, in their origin, attempt to be recreated societies built on the influence of a single individual: Jesus, Buddha, Lao Tzu, Mohammed, or at most a small group. Such teachers signify, by their appearance, that there are individuals to whom a society should be related, rather than the other way around. Within a generation or two, however, this new society has become one more social contract, and the individuals of the new generations are once again subordinated to it.

Paul’s conception of Jesus as the genuine individuality of the individual, which is what I think Simone Weil is following here, indicates a reformulating of the central Christian metaphor in a way that unites without subordinating, that achieves identity with and identity as on equal terms. The Eucharistic image, which she also refers to, suggests that the crucial event of Good Friday — the death of Christ on the cross — is one with the death of everything else in the past. The swallowed Christ, eaten, divided, and drunk, in the phrase of Eliot’s Gerontion, is one with the potential individual buried in the tomb of the ego during the Sabbath of time and history, where it is the only thing that rests. When this individual awakens and we pass to resurrection and Easter, the community with which he is identical is no longer a whole of which he is a part, but another aspect of himself, or, in the traditional metonymic language, another person of his substance. (CW 19, 119-20)