Bruno makes appearances throughout Frye’s work, beginning with his students essays in the 1930s. His most extensive commentary on Bruno is in “Cycle and Apocalypse in Finnegans Wake.” Here’s a selection from that essay.

As literary masters, the Italians predominate in Joyce over all other non-English influences. Joyce’s great debt to Dante, at every stage of his career, has been fully documented in a book-length study, and he owed much to other Italian writers, including Gabriele D’Annunzio, who cannot be considered here. But Finnegans Wake is dominated by two Italians not previously represented to any extent in English literature. One is Giambattista Vico, whom Joyce did much to make a major influence in our intellectual traditions ever since. The other is Giordano Bruno of Nola, in whom no previous writer in English except Coleridge seems to have been much interested, although he lived in England for a time and dedicated his two best-known books to Sir Philip Sidney.

During the years when Joyce was working on Finnegans Wake, publishing fragments of it from time to time under the heading of Work in Progress, a group of his disciples brought out a volume of essays with the eminently off-putting title of Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress. The first of these essays, by the disciple whose name is by far the best known today, Samuel Beckett, was on Joyce’s debt to Italian writers, more especially Vico. Despite Beckett’s expertise in Italian—all his major work reflects a masterly command of Dante—the essay is very inconclusive, mainly, I imagine, because the entire structure of Finnegans Wake was not yet visible, and the essays were designed to point to something about to emerge and not to expound on something already there. However, since then every commentary has been largely based on Joyce’s use of Vico’s cyclical conception of history.

Vico thinks of history as the repetition of a cycle that passes through four main phases: a mythical or poetic period, an age of the gods; then an aristocratic period dominated by heroes and heraldic crests; then a demotic period; and finally a ricorso, or return to chaos followed by the beginning of another cycle. Vico traces these four periods through the Classical age to the fall of the Roman Empire, and speaks of a new cycle beginning in the medieval period. In the twentieth century Spengler worked out a similar vision of history, although he uses the metaphor of organisms rather than cycles. Spengler influenced Yeats to some degree, but not Joyce. The first section of Finnegans Wake, covering the first eight chapters, deals with the mythical or poetic period of legend and myths of gods; the second section, in four chapters, with the aristocratic phase; the third, also in four chapters, with the demotic phase; and the final or seventeenth chapter with the ricorso. The book ends in the middle of a sentence which is completed by the opening words of the first page, thus dramatizing the cycle as vividly as words can well do.

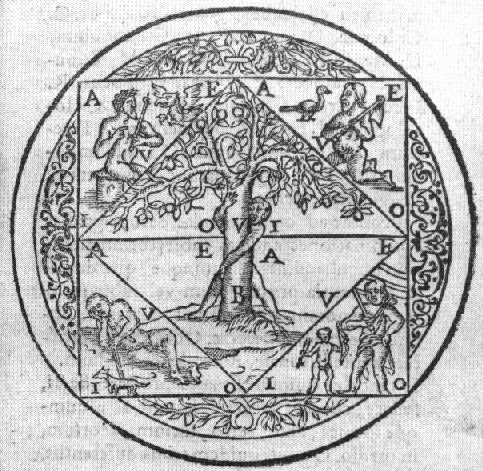

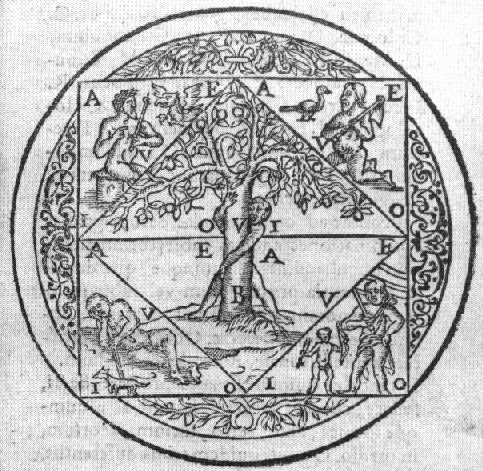

In contrast, there seems relatively little concrete documentation for the influence of Bruno of Nola, and one of the most useful commentaries, which has Vico all over the place, does not even list Bruno in the index. Yet Bruno was an early influence, coming to Joyce’s attention before his growing trouble with his eyesight forced him to become increasingly dependent on the help of others for his reading. In his early pamphlet, “The Day of the Rabblement,” he alludes to Bruno as “the Nolan,” clearly with some pleasure in concealing the name of a dangerous heretic under a common Irish one. What the Nolan said, according to Joyce, was that no one can be a lover of the true and good without abhorring the multitude, which suggests that the immature Joyce, looking for security in a world where his genius was not yet recognized, found some reassurance in Bruno’s habitual arrogance of tone. Bruno’s “heresy,” evidently, seemed to Joyce less an attack on or repudiation of Catholic doctrines than the isolating of himself from the church through a justified spiritual pride—the same heresy he ascribes to Stephen in the Portrait. As far as Bruno’s ideas were concerned, Joyce was less interested in the plurality of worlds, which so horrified Bruno’s contemporaries, and concentrates on a principle largely derived by Bruno from Nicholas of Cusa, who was not only orthodox but a cardinal, the principle of polarity. Joyce tells Harriet Shaw Weaver in a letter that Bruno’s philosophy “is a kind of dualism—every power in nature must evolve an opposite in order to realize itself and opposition brings reunion.” Most writers would be more likely to speak of Hegel in such a connection, but that is not the kind of source one looks for in Joyce. In the compulsory period of his education Joyce acquired some knowledge of the Aristotelian philosophical tradition, and learned very early the numbing effect of an allusion to St. Thomas Aquinas. But there is little evidence that the mature Joyce read technical philosophy with any patience or persistence—not even Heraclitus, who could have given him most of what he needed of the philosophy of polarity in a couple of aphorisms.

In a later letter to Harriet Weaver, Joyce says, referring to both Vico and Bruno: “I would not pay overmuch attention to these theories, beyond using them for all they are worth.” That is, cyclical theories of history and philosophies of polarity were not doctrines he wished to expound, the language of Finnegans Wake being clearly useless for expounding anything, but structural principles for the book.