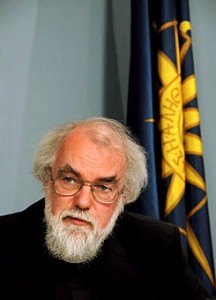

Rowan Williams is stepping down as Archbishop of Canterbury at the end of this year, and has taken the opportunity to remove the muzzle and openly attack David Cameron’s idea of Great Britain’s “big society.” He calls it

aspirational waffle designed to conceal a deeply damaging withdrawal of the state from its responsibilities to the most vulnerable. And if the big society is anything better than a slogan looking increasingly threadbare as we look at our society reeling under the impact of public spending cuts, then discussion on this subject has got to take on board some of those issues about what it is to be a citizen and where it is that we most deeply and helpfully acquire the resources of civic identity and dignity.

This critical and prophetic language reminds us of the genuine role of the church in society. Williams’ attack is especially resonant amid the scandal of shameless interest rate rigging at Barclays in Great Britain and of similar fraud and collusion by investment bankers in the United States. For more on the Barclay scandal, go here. For Matt Taibbi’s scathing article in Rolling Stone–his disgust is palpable–go here.

Williams’ book Faith in the Public Square will by published by Bloomsbury this September. Go here for more details. Here are a few more nuggets:

At the individual and the national level, we have to question what we mean by growth writes. The ability to produce more and more consumer goods (not to mention financial products) is in itself an entirely mechanical measure of wealth. It sets up a vicious cycle in which it is necessary all the time to create new demand for goods and thus new demands on a limited material environment for energy sources and raw materials. By the hectic inflation of demand it creates personal anxiety and rivalry. By systematically depleting the resources of the planet, it systematically destroys the basis for long-term wellbeing. In a nutshell, it is investing in the wrong things.

‘Big society’ rhetoric is all too often heard by many as aspirational waffle designed to conceal a deeply damaging withdrawal of the state from its responsibilities to the most vulnerable.

The significance of trying to shape public opinion within the Church is something quite different from an institutional programme on the part of the Church to impose its vision on everybody else.

Religion is seen by those who find it unacceptable as essentially an appeal to the will – decide to obey these presuppositions and to obey these commands. Religion in fact is consistently against coercion and institutionalised inequality and is committed to serious public debate about common good.

These remarks bring to mind so many passages in Frye, but his discussion in “The Church: Its Relation to Society” (1949), written at the beginning of the Cold War, is particularly prescient. The managerial or oligarchic dictatorship he describes here perfectly applies to the world of resurgent capitalism and “permanent war” we have been living in for decades now, ever since the Reagan and Thatcher “revolutions”:

It should be realized that Protestantism, like Catholicism, has had to struggle with a sacrilegious parody of itself, a struggle far harder to get one’s bearings in than the other. This parody is best described as laissez-faire, the industrial anarchism which represents the doctrine of individual liberty transferred from the society of love to the society of power.

After benefiting greatly from capitalism as long as it was dissolving the concretions of feudal. authority, Protestantism was considerably baffled when it turned demonic with the Industrial Revolution. The uninhibited grabbing of corruptible possessions, conceived not as a perennial fact of human nature but as a programme of human action, is the first open defiance of law and Gospel in modern history, for even the revolutionary Deism which preceded it made moral ideals out of Christian conceptions. As Ruskin points out in his trenchant polemic Unto This Last, the merchant under laissez-faire, unlike professional men, has no “calling,” no antecedent social reason for his existence.`’ Hence he cannot make any sacrifice of his natural will. From this fact two fallacies designed to rationalize laissez-faire have originated. One which goes back to Rousseau, is the conception of the “rights of man” as identical with the natural will of man. The other is the conception of history as the working out of the will of the natural society. The latter is sometimes called social Darwinism, because it misapplies Darwin’s biological theory to history, and, presents us with a vision of historical progress through the survival of the fit, the fit being those who fit the progress of laissez-faire by the possession of an unusually strong lust for power and profits. These two major fallacies have spawned a fruitful brood of minor ones, which we should take care, in talking about “liberalism,” to distinguish from those which are essential to a coherent Christian outlook.

The defences of laissez-faire offered today usually assume that the political form of it is democracy. This is nonsense: its political form is an oligarchic dictatorship. Every amelioration of labour conditions, every limitation of the power of monopolies, every effort to make the oligarchy responsible to the community as a whole, has been forced out of laissez-faire by democracy, which has played a consistently revolutionary role against it. . . . The essential identity of interest between the tendency to dictatorship in America and the achievement of it in Russia has been stated, though with some distortion of emphasis, in James Burnham’s well known book, The Managerial Revolution. How such a revolution could make its power absolute and permanent by a not-too-lethal form of permanent war is shown with great clarity in George Orwell’s terrible satire 1984, perhaps the definitive contemporary vision of hell. (CW 4, 263-64)

My response to this post can be found at http://canadianatheist.com/2012/07/09/rowan-williams-and-northrop-frye/

The “society of love” is the church, or the Christian community, Veronica, and Frye happens to be a Protestant speaking to a Protestant audience. He is really speaking about the Christian’s relation to society, not the church’s. And the Christian’s relation to the “society of power” is one of keeping the vision of another kind of society constantly in mind and acting according to that vision and building up what Blake calls The Human Form Divine. It’s not my argument you don’t find compelling. It’s Frye’s.

What do you think the genuine relation of the church is to society, or do you feel it just doesn’t have one? I guess the latter, given that your comments are posted at a site called “The Canadian Atheist.” Whether you are religious or not, however, there is no doubt that Rowan Williams speaks with a great deal of moral authority, and that that authority would not exist without the existence of an Anglican church.

Your post, Veronica, is rebutted by Frye himself in the same piece that Dr. Adamson cites. The last paragraph of “The Church: Its Relation to Society” is striking in its acknowledgement of the Church’s failures–and the author’s conviction of the potential it still has to be, in Niebuhr’s typology, an example of Christ Transforming Culture:

“It [[the church]] must learn again to present its faith as the emancipation and the fulfilment of reason. It has been tempted by the world to condemn human liberty as an illicit encroachment on the divine prerogative. It must learn to explain once more how it is God’s will that man should be free. But it may well be that the church is nearing the end of its period of temptation: if so, it can enter upon its ministry anew, coming among men eating and drinking, making friends with publicans and sinners, insisting that thieves get out of its temple, ridiculing hypocrites and helping the blind to see, befriending Lazarus and warning Dives [cf. Luke 16.19-31], going about doing good and turning the world upside down.” (CW 4:267]

We do well to remember and apply Frye’s words earlier in the piece–that we must read the Republic with “Christianity’s absolute separation of the kingdom of God from the kingdom of fallen men kept clearly in mind” (4:255)–when we consider both religion in general, and Christianity and the Church in particular. The Church is human: it’s eminently fallible, and we need not look far for evidence; the Church is holy and is transformed to be able to speak good news–to articulate and celebrate the kerygma–that we may enter the kingdom.

It seems to me that Rowan Williams’ words are worth reading not just in the context of how the Church can be an effective critic not of trivial moralistic pieces as it has too often, but rather of the deep structures that affect the common good.

And to elucidate Williams’ remarks about

“The significance of trying to shape public opinion within the Church is something quite different from an institutional programme on the part of the Church to impose its vision on everybody else.”

we might turn to a prescient sentence in “The Church: Its Relation to Society”: “The society of power always tends to resemble the pyramid or tower of Babel: the society of love tends to resemble the communion table. To paraphrase a punning argument of Milton’s, ‘ruling’ in the spiritual sense is not physical compulsion but the application of the ‘rule’ or measuring reed of the temple of God to human society.” (4:256)

Thank you, Dr. Adamson, for pointing me to an essay I’ve not looked at it in too long–it’s always a gift to be reminded of Frye’s nigh infallible ability to speak to current happenings and thought!

Joe

I have no objection to Frye or what he says in the passage you quoted in the post. Frye is the one who was relieved when “the whole shitty and smelly garment (of fundamental teaching I had all my life) just dropped off into the sewers and stayed there.” It is your argument for the genuine role of the church in society I don’t find convincing. However, the church does play a role in society; it plays an especially pernicious role by exploiting and controlling its followers and by trying to exploit and control the whole world.

Your assertion “there is no doubt that Rowan Williams speaks with a great deal of moral authority, and that that authority would not exist without the existence of an Anglican church” is a circular argument you offer to support your claim that the church plays a genuine role in society.

I was not making an argument, Veronica. I was making some observations. Rather than labour the point, I refer you to Matthew’s very helpful clarification in his comments. But for the record, the “shitty and smelly garment” passage concerns Frye’s exhilarating sense of liberation from fundamentalism, not from the prophetic Christianity which he most certainly did not abandon. His last book, The Double Vision, is his fullest statement on the matter and on the kerygmatic or meta-literary dimension of language. The most complete treatment of this aspect of Frye’s work is Bob Denham’s Northrop Frye: Religious Visionary and Architect of the Spiritual World.

In response to Veronica’s post, I am a member of a small Methodist church (ca. 40 members) in a small town (pop. 300). I don’t see that our little church “plays an especially pernicious role by exploiting and controlling its followers and by trying to exploit and control the whole world.” Our church rather seeks to live out what Frye calls “the gospel of love.” One of the things this means in our case is a commitment to the social gospel: helping feed the hungry (we support our local food pantry), helping clothe our children (we send clothes and shoes to the less fortunate children at our local elementary and middle schools), helping provide shelter by supporting our local Habitat for Humanity (we have recently contributed some $50,000 to building two homes). We have no interest whatsoever in trying to exploit and control the whole world. What we are interested in is trying to brighten the corner where we are. Institutions, like human beings, are fallible. That means not that we should scrap our institutions (political, educational, religious, civic, et al.) but that we should seek to improve them.

You know, Robert, I sympathise with you and your small Methodist church, and no doubt you and your fellow-parishioners do your share to brighten your corner of the world. However, a parish of a church is not the church itself, and, contrary to what the Archbishop of Canterbury says, churches are not, as he suggests,

It would be nice to think so, but the archbishop’s church has just been involved in a large-scale exercise to oppose government regarding gay marriage. He has spoken in the House of Lords against assisted dying in a skewed and demonstrably scare-mongering way. Churches oppose everything from abortion to birth control, and they endeavour to have their beliefs written into law, or to keep them enshrined there.

So, yes, indeed, individual Christians and Jews and Hindus and Muslims no doubt do good things and contribute to the welfare of others, but churches, as corporate institutions in society, can work enormous harm, and the archbishop’s claims about what the church stands for is simply false. I think, if you read Veronica’s post again, you will see that she does not deny the good that religious individuals may do, but her concern is much more focused on institutional wrongdoing. Interestingly, at the institutional level churches point to the good that their members do in order to justify far more sweeping claims about what their role should be in public decision making.

While I know next to nothing about Northrup Frye — having read his Anatomy of Criticism many many years ago, and bits of his The Great Code — but I see little relationship between Frye and Williams. Of course, Williams wears many hats. As an archbishop he has acted in many cases contrary to the public good, in my estimation, despite is sensitive interpretations of Dostoyevsky. His criticisms of David Cameron’s Big Society would be more convincing if he had some suggestions as to how we can create economic systems that are not premised on growth. Until then, we are stuck with continuing to consume our resources at an unsustainable rate, and religious criticism will get us nowhere. This is an economic and justice issue of great complexity. I doubt whether the archbishop has the expertise to resolve the problems associated with it.

Eric, thank you for your comments. I think that your concerns have been answered by both Matthew and Bob. It comes down to Bob’s question: do you want to improve institutions, or just scrap them, so that there is an even more muted critical voice in society? We can argue about your objections till the cows come home, but the real question for this blog is Frye’s views and what he said in his very early days stood with him throughout his life: that the only two cultural areas that gave hope for the potential transformation of human societies are art/literature and religion.

i meant to say too that it is belittling to dismiss so condescendingly the brightening of small corners of the world. If everybody acted that way the world would be a much better place than it is now.

Joseph, I didn’t perceive a belittling or condescending tone to Eric’s reference to the work of the local church. Nor do I think his concerns about problems at the institutional level of religions have been fully answered. Religions have done plenty of good & bad through history. Some see a glass on the way to being filled w/ spirit, some see a glass largely drained of spirit.

In the article you mention under “Celebrating Frye’s 100th Birthday,” Robert Fulford says,

“For an ordained United Church clergyman, Frye had a somewhat strained relationship with God and Christianity. ‘I find the Gospels most unpleasant reading,’ he wrote. ‘The mysterious parables with their lurking & menacing threats, the emphasis placed by Christ on a ‘me or else’ attitude, the displaying of miracles as irrefutable stunts’ — he found it all questionable. He wondered how long people could dodge the suggestion that the editorial shaping of Scripture was a fundamentally dishonest process.

He took a sharply critical view of the United Church itself. When he heard that a fellow Protestant had become a Roman Catholic, he became uncomfortable — not just because he thought the Catholics anti-liberal and anti-democratic but because ‘this fatuous United Church’ couldn’t begin to compete. Lacking intellectual integrity, it seemed to him no better than a committee of temperance cranks. Certainly he would never try to persuade anyone to become a member.

As for the Almighty, Frye believed that, ‘the worst thing we can say of God is that he knows all. The best thing we can say of him is that, on the whole, he tends to keep his knowledge to himself.’”

Fulford’s description does not support your thesis that in Frye’s view, “the only two cultural areas that gave hope for the potential transformation of human societies are art/literature and religion.”

Joseph Adamson, you said:

Was I condescending? I didn’t mean to be, and I am grateful that Jim Racobs recognised this. Certainly, individual Christians, and smaller religious communities do good. Why should I deny that, or be condescending about it? I shared, myself, in such communities, as an Anglican priest, and remember that participation with fondness. All that I pointed out was that, in practice, churches do not, as Williams claims, act in ways that are “consistently against coercion and institutionalised inequality.” I think this is demonstrably false.

For that reason I would want to question Frye’s conviction that “the only two cultural areas that gave hope for the potential transformation of human societies are art/literature and religion” — if, that is, that is what Frye thought (but see Veronica’s comment immediately above). This seems to me hopelessly wrong. To suggest that science, for example, has no potential for transforming human societies seems to me to be astonishingly short-sighted. And to think of religion itself — based, as religions are, on such diverse and conflicting histories, and tied up, as they all are, in hermeneutical knots — has much to contribute to the transformation of society, seems hopelessly parochial.

I admit to ignorance of Frye’s writings on social and religious themes — nor did I comment because of my familiarity with Frye or my commitment to his social vision — but it strikes me that much of his seminal work was done long before the religions began to meet in significant numbers in the same social and political space, where their conflicts and disagreements have become more immediately obvious. And, as Veronica points out just above, Frye’s own relationship with religion was not without its tensions. Like me, apparently, Frye read the gospels, not only with reserve, but discomfort. The contemporary social vision of Christianity is largely, I believe, the product of reading Christian texts in the context of the Englightenment, and today Christian renewal tends as often towards regression to a know-nothing fundamentalism, as it does to a reasonable and compassionate humanism. This is particularly obvious when it comes to the position of women — and their liberty rights with regard to reproduction — the acceptance of alternate sexualities, the rights of the dying, the indoctrination of children, and many other things that involve the apparent inability or reluctance of most religions to rid themselves of dogmatic baggage from the past.

Before speculating on what Frye does and does not think about the church, it would be well to take a look at what he has had to say about the subject. There is a great deal in his books and essays about the church, and I count almost 800 references to the church in his notebooks and diaries. As several people have already addressed the relation of Frye and the church, it would be well to look at what they have to say. These include:

Douglas Jay. “Undercover for the United Church.” The Observer [United Church of Canada] 64, no. 6 (January 2001): 44–5. On Frye’s relation to the United Church of Canada.

Jean O’Grady. “Frye and the Church.” In Jeffery Donaldson and Alan Mendelson, ed. Frye and the Word: Religious Contexts in the Criticism of Northrop Frye. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003. 175–86. On Frye’s love hate relationship with the United Church of Canada.

Russell Perkin. “Northrop Frye and Catholicism.” In Jeffery Donaldson and Alan Mendelson, ed. Frye and the Word: Religious Contexts in the Criticism of Northrop Frye. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003. 187–202. On Frye’s conflicted relationship with the Catholic Church and its doctrines.

Ian Sloan. “The Reverend H. Northrop Frye.” In David Rampton, ed., Northrop Frye: New Directions from Old. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2009. 105–22. On the significance of Frye as a theologian and on his stance toward the church.