Frye in “Varieties of Literary Utopia”:

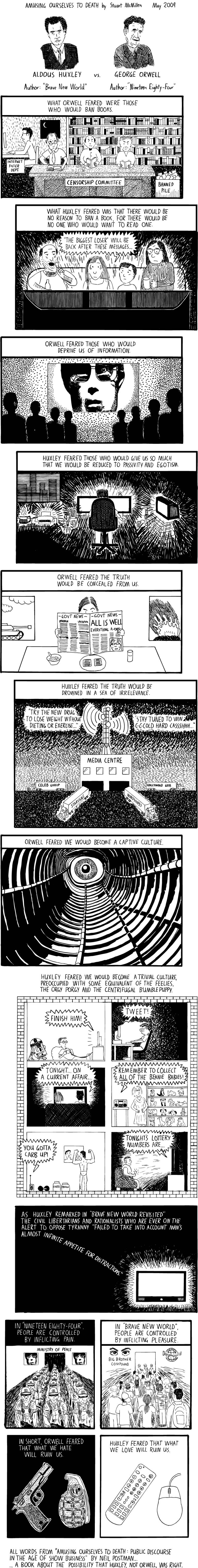

A certain amont of claustrophobia enters this argument when it is realized, as it is from about 1850 on, that technology tends to unify the whole world. The conception of an isolated Utopia like that of More or Plato or Bacon gradually evaporates in the face of this fact. Out of this situation come two kinds of Utopian romance: the straight Utopia, which visualizes a world state assumed to be ideal, at least in comparison with what we have, and the Utopian satire or parody, which presents the same kind of social goal in terms of slavery, tyranny, or anarchy. Examples of the former in the literature in the last century include Bellamy’s Looking Backward, Morris’s News from Nowhere, and H.G. Wells’s A Modern Utopia. Wells is one of the few writers who have constructed both serious and satirical Utopias. Examples of the Utopian satire include Zamiatin’s We, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and George Orwell’s 1984. There are other types of Utopian satire which we shall mention in a moment, but this particular kind is a product of modern technological society, its growing sense that the whole world is destined to the same social fate with no place to hide, and its increasing realization that technology moves toward the control not merely of nature but of the operation of the mind. (CW 27, 194-5)

Am I the only one sick of this site’s splurge of silly graphic comics and pop artist promos? Stop it! I love the idea of the Frye site. Not everything has to be about the great NF. But we can get pop trash all over, and we should not infect this important platform with pop banalaties. We don’t have to be solemn. Frye may have seemed so to some but he was not. The irony under that proper face was one of the great joys of listening to him. Can we not have some respect without seeming old fashioned?

Hi Bob. First, with regard to the post your comment is attached to, it’s hard not to be struck by the rise of phenomena like the graphic novel as well as its shorter forms, like the one reproduced in today’s post. I refer to this kind of thing not only because is it a part of our culture now, but also because it is evident from the diaries and notebooks and especially the interviews that Frye was always keeping an eye out for it himself. He had something to say about Bob Dylan, the Beatles, rock’n’roll, and even punk rock. I think that with this sort of cartoon, he’d’ve been struck by how an otherwise frivolous form of entertainment can be so readily adapted to deal responsibly with issues of real concern. And, in this instance, I included, as I always try to do, a pertinent quote from Frye. I know that other readers I hear from seem to enjoy the way in which Frye can still shed light on contemporary social, cultural and even political issues. I regard it as part of his remarkably prophetic outlook, and it’s always a treat for me to discover an otherwise unexpected link from Frye’s past to our present — and more often than not to what looks like our future too. It’s what makes Frye Frye.

As to the other “pop trash,” I confess I’m not sure what you mean. While Frye always tended to his responsibilities as a scholar first, it’s apparent he also took on the world as he found it and was very willing to comment on it. If, for example, Frye takes the trouble in an interview to talk about the descent of the animated cartoon from the puppet show (while also admitting that watching a silent film caused him to fall out of his seat with laughter), then I figure it gives us license to look at the cartoons that thrived in his day (and still survive in ours) as a way to raise an issue that might tend to get overlooked, even by Frygians. Because the blog is daily, it does by its nature invite as direct an encounter with everyday life as we can manage in a way I characterize as “Frye-relevant.” Our number of daily visitors is now about 16,000 per month, and has been rising steadily for many months now — that number, for example, represents a 60% increase since just May. My one regret is that this blog has not been as interactive as it still might be, but I think I can assume that people come here to read what’s on offer because they like what they see. My approach to Frye is in the round: to look at him as a scholar as well as man of his time, and, it turns out, of our time too.

I take no issue with the comics, or the videos, or the many other pop culture references in this blog. The alignments between Frye and everything else conceived here is refreshing, innovative and topical. Sheesh, too, it’s just got to demand a lot of sweat labor digging up all those excerpts from Frye’s corpus. I’m grateful for effort.

Charitably, though, I sympathize with Bob’s view to the extent that Frye’s work has also encouraged a posture of detachment from the pathologies of our own era. I mean, if Frye suggested that the purpose of a liberal education is to make us “maladjusted” to society, finding slick ways to mainstream Frye starts to look like an “adjusted” conformity.

Bob’s easiest remedy, of course, is to retire to the solace of reading Frye’s works, in the comfort of one’s favorite armchair.

In the end, I recall Frye’s urging that judgment of creative works should not be job of the critic. Those comics, thus, occupy the realm of art just as much as Keats or Blake. Ironically, William Blake, we ought to remember, produced his own kind of proto-comics, and this artist/poet preoccupied Frye over his entire life.

Thanks, Bob. I agree with your point that becoming maladjusted to society is really what Frye is about. I’m squirming to think that what I do here might be regarded as anything but a promotion of that. All of the pop culture stuff I include, even when it’s more or less mainstream, tends to be from the arts that have their roots in subversion — at least to the extent that they usually drive both parents and repressive brands of conservatism crazy.

Popular culture is a large part of the language most people speak, and it might also be justifiably regarded as an expression of creative energy that a critical understanding of it can enhance. If the arts are a potentially prophetic expression of what Frye calls primary concern, then that concern is manifest wherever there is cultural activity. Again, if Frye can fall out of his seat with laughter at a silent movie, then why shouldn’t we confess to and examine the pleasure we get from the popular culture that currently surrounds us? I can find almost nothing to be offended by in the arts when confronted with the rise of plutocracy, the fiendishly disproportionate distribution of wealth, and the open admission of war crimes by politicians who believe that they are above the law simply because Fox News says so. I posted a while ago on Frye and obscenity. Frye characterizes what we typically call obscenity as “profoundly moral.” Once that confusion is out of the way, it’s much easier to recognize what is genuinely obscene.

This blog ranges in all compass directions so it would be difficult or unfair to suggest it examines them in a deterministic way. Nevertheless, I’m reminded of Frye’s critique of deterministic criticism in AC where he suggests that this happens when an alignment is made between the literary subject and that which the critic is really interested in. E.g. history, psychoanalysis, biography etc.

Here the world of events, characters and culture get drawn into alignment with Frye…and that’s okay! Lucky for us, Frye’s erudition is encyclopedic, his mythology, like Blake’s or Milton’s, swallows the whole world…whole. Comics and silent movies occupy that world.

I’m late to the party as usual, but put me in the Happy/Ashley camp on this one. Remember that NF said any imaginative verbal structure was fair game. One of the things I like about this site is that it’s a place to which I can point when someone (e.g., a student) wants to know if NF is still “relevant.” Like Whitman’s speaker, Frye’s range is large; it contains multitudes.

Better late than never, perfesser. Your invitation, like our door, is always open.