Frye’s Superlatives: The Mysterious Case of Edgar Allan Poe

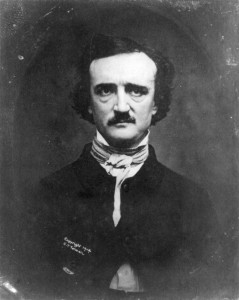

Another surprise in Frye’s superlatives might be Edgar Allan Poe, who in the list compiled by Bob Denham is dubbed “[t]he greatest literary genius this side of Blake.” These are mighty words, and puzzling, it would seem. Poe, of all people. Really? However odd it may strike us, it is indicative of Frye’s conception of literature. Poe is cited extensively throughout Frye’s work. In Anatomy, for example, Frye contrasts the art of Poe with the more inhibited genius of Hawthorne. “Hawthorne’s inhibitions,” he observes, “seem to be at least in part self-imposed, as we can see if we turn to Poe’s ‘Ligeia,’ where the straight mythical death and revival pattern is given without apology. Poe is clearly a more radical abstractionist than Hawthorne, which is one reason why his influence on our century is more immediate.” Beyond the many references in Anatomy, Poe is a favorite go-to-guy in The Secular Scripture, and a stalwart in the Late Notebooks and Words with Power. Frye has nary a word against the man, in sharp contrast with most of the critical establishment. Poe generally elicits quick dismissal, or at best skepticism. Yet he was sanctified by the two greatest French poets of the nineteenth century, Baudelaire and Mallarmé. Frye makes the point in The Secular Scripture: “Another fiction writer who specializes in setting down the traditional formulas of storytelling without bothering with much narrative logic is Edgar Allan Poe. This fact, along with the ascendancy of realism, accounts for the curiously schizophrenic quality of Poe’s critical reception. There have been no lack of people to say that Poe is fit only for immature minds; yet Poe was the major influence on one of the subtlest schools of poetry that literature has ever seen.” The same point is made in the notebook entry the first sentence of which is quoted by Bob. It is worth quoting at greater length: “The greatest literary genius this side of Blake is Edgar Allan Poe–that’s why he’s regarded as fit only for adolescents, or French poets who don’t really know English. I don’t apply this to the poetry, but there’s no prose tale, however silly, that doesn’t hit an archetype in the bullseye.” How could Poe’s tales and critical theory not endear him to Frye? Poe was unashamedly anti-mimetic, a perfect archetypal genius, a purely poetic allegorist, and an extravagantly otherworldly cosmologist.

A side note to Bob Denham and Russell Perkin, concerning Poe and Wilde and Hopkins: even beyond his influence through the Symbolistes and decadents like Huysmans, Poe seems to have made a deep impression on Wilde, a writer admired in the very same spirit by Frye. It is years since I have read it, but I recall that The Picture of Dorian Gray echoes in several places Poe’s great double story, William Wilson. He may not have been an influence on Hopkins but it was Poe, after all, who first introduced the idea of the primacy of the underthought, or allegorical undercurrent of suggestion, over the manifest meaning of the poetic or literary text.

I looked recently, just out of curiosity, at Harold Bloom’s article on Poe written twenty-five years ago in The New York Review of Books (Volume 31, Number 15 · October 11, 1984). It is a telling piece. Bloom has little time for Poe, and fails poor Eddie in everything but – significantly enough — his precocious knack for archetypal logic. At least Bloom got that right. He finds an analogy in C.S. Lewis’s attitude to George MacDonald, whose writings, according to Lewis, demonstrate the power of mythological structures over and above any particular talent or gift for writing. MacDonald, of course, is another, if much less important Frye touchstone.

And thanks to Michael Happy for the Wilde quotation: Rufus Griswold’s notorious maligning of Poe is one of the best examples of the biographer-as-Judas.