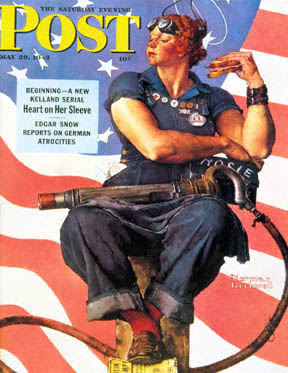

1942: Frye reveals that he’s a man of his time when it comes to women in wartime. He was clearly not yet familiar with this iconic figure, Rosie the Riveter, pictured above.

[90] Speaking of war, I sometimes feel that women are bad for morale: they go in for catastrophe, funerals & oracles. They’re the sex of Cassandra, and they’re extremely short on humor. They hate obscenity, an essential part of humor, and the female magazines never go in for it. Cartoons, jokes, breezy comic stories, have little place in the Ladies Home Journal. It isn’t just mediocrity: the male magazines for mediocrities always have humor: but what the average woman wants is something maudlin to attach her complex of self-pity and I-get-left-at-home and my-work-is-never-done and nobody-appreciates-it-anyway to. There’s something morbid about the domestic mind which weeps at weddings and gets ecstatic over calamities. During the war they keep making woo-woo noises prophesying large drafts & taxes with no we’ll-get-along-somehow reserve. Partly of course because they’re not in it. If people only believed in immortality & a world of spiritual values! But it might only make the war more ferocious.

1950: Frye’s account of the “Frye is God” lore that was then popular.

[585]… There was also a letter from Irving attached to his new essay for the Americans [it is not clear which paper Frye is referring to here]. A story in it about a freshman coming to Victoria to take an R.K. course from Professor Frye. When he begins he believes in God: when he gets to Christmas he believes in Frye’s God: when he comes to the end of the year he believes Frye is God. As a matter of fact I’ve known for some time that undergraduates used to refer to me casaually as “God” in their conversations. It’s a strain to live up to that, & doubtless of some theological interest to know that God gets a hell of a dose of hay fever every year at this time: maybe that’s why so many wars start in August & September.