Bob Denham has kindly sent my way the following two links, here and here, to the website of Andrew J. Siebert, a teacher and blogger. Siebert offers an intelligent and engaged response to Frye’s writings on education.

Author Archives: Joseph Adamson

New Translation into Japanese

Bob Denham has sent me the following news:

Shunichi Takayanagi’s translation into Japanese of Frye’s Creation and Recreation has just appeared (Tokyo: Shinkyo Shuppansha, 2012). Takayanagi previously translated Myth and Metaphor (2004).

The same publisher has just released a translation of The Double Vision.

The total number of Frye’s books now translated into Japanese is seventeen.

Also courtesy of Bob, three other Frye alerts: here Bob engages in discussion with a blogger and writer who has some preliminary thoughts after reading Anatomy of Criticism.

Here in The Toronto Star the poet Don Coles pays homage to our oracle, “the greatest oracle of our age,” as Martin Knelman calls him. Coles’ piece is a response to Knelman’s column in the same paper, which you can find here.

Barbara Kay in The National Post on the power of myths in shaping history, here.

The Electronic Symposium

(Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s “The Symposium”)

On 17 August 2009 Michael Happy launched the Northrop Frye weblog. Michael wrote at the time that “the purpose of this blog is to provide an online meeting place for the Frye community, which, we hope, will extend beyond the university to include those who maintain a lively interest in literature and the arts.” Michael, who ran the blog almost singlehandedly for more than two‑and‑a‑half years, poured an enormous amount of energy into it. He has recently taken a break from the daily attention the blog requires.

Joe Adamson, who was a correspondent from the beginning, has taken over the administrative duties from his post at McMaster University (the library at McMaster hosts the blog). This month marks the third anniversary of the blog, which continues to receive between 8000 and 9000 visitors each month. In light of that anniversary and of Frye’s 100th birthday earlier this month, it seems to be an appropriate moment to renew the call for contributors. If you have something to say about Frye or about what others have said about him and his work, then by all means let us hear from you. Just write to us at adamsonj@mcmaster.ca, or if you would like to remark on someone else’s post, simply go to “Leave a Comment” at the end of the post. All contributions are, of course, moderated.

Ed Lemond, bookseller, poet, novelist, and longtime advisor to the program committee of the annual Frye Festival, has recently agreed to be a regular correspondent from the Maritimes. We would like to have other regular correspondents. This doesn’t mean that you would be obligated to post something every week or even every other month. But it does mean committing yourself to engaging in the conversation periodically.

The ideal is to create an electronic conversation somewhat like the Platonic symposium––a dialectic of both different points of view and of a common vision of the subject under discussion. We look forward to hearing from you.

Joe Adamson and Bob Denham

Photo from the Centenary in Moncton

From “Frye Statue Celebrates an Icon,” by Margaret Patricia Eaton, Moncton Times, July 12, 2012:

At the unveiling of the Northrop Frye sculpture on July 13 am, standing (from left), Janet Fotheringham, resource and art critic for the project; Dawn Arnold, Frye Festival chair and a Moncton city councillor, Darren Byers and Fred Harrison, sculptors. Sitting next to the Frye statue is Robert Denham, Professor Emeritus at Roanoke College in Virginia, who donated his entire personal collection of writing by and about Frye, valued at $40,000, to the Moncton Public Library. Next to Frye on the bench seat is a book with the following bilingual inscription: “Northrop Frye: Canadian literary critic and theorist considered one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th Century. He spent his formative years in Moncton where he developed the ideas that he would go on to explore the rest of his life and where he established his deep commitment to an informed and civil society.”

And from Bread ‘N Molasses, “Community Birthday Party to Celebrate Northrop Frye’s 100th Birthday,” by Kellie Underhill, June 28, 2012:

Before the unveiling of the sculpture, the Frye Festival in collaboration with the New Brunswick Public Library Service will announce a major donation by Robert D. Denham to the Moncton Public Library. Professor Emeritus at Roanoke College in Virginia, Robert D. Denham is donating his complete collection of books and objects that belonged to Northrop Frye, along with Frye’s manuscripts, first editions of his books and many other works that feature Frye.

“The New Brunswick Public Libraries Foundation, the New Brunswick Public Library Service, and the Moncton Public Library would like thank Dr. Robert D. Denham, the foremost Northrop Frye scholar in the world, for his generous donation of one of the largest Northrop Frye collections,” says Sylvie Nadeau, Executive Director of New Brunswick Public Library Service. “This eclectic collection includes signed editions of Frye’s works including first editions, paintings and caricatures depicting Frye, audio-visual materials featuring Frye and other treasures that both researchers and the public will enjoy. A highlight of the collection is Frye’s own writing desk and chair from the upstairs room in his Toronto home, which will join Frye’s typewriter at the library. The value of the donation has been appraised at over $40,000. I would like to thank the Frye Festival organization and the Board of the Moncton Public Library for their key role in facilitating this donation.”

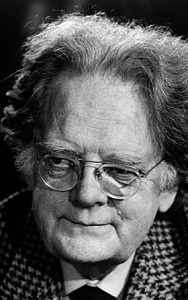

Happy Birthday, Northrop Frye!

It is Frye’s centenary today, his 100th birthday, an occasion of celebration for anyone interested in the way a great thinker can change the way we think about literature, society, and culture, and the way a public intellectual can touch not just academics and scholars and those who are part of a university environment, but of so many individuals who are not. He spoke for and to us all, and with an insight and eloquence that are unparallelled. Most importantly, he spoke the language of love, not the language of power.

Happy Birthday, Norrie!

Above is a photo of the bronze state which was unveiled yesterday in Moncton.

In Response to Comments on Frye and Religion

In response to comments on my post on Rowan Williams and Frye (here), I am not really interested in getting into a discussion about whether the world would be better or worse without religion or the belief in God. The question is what are Frye’s views on the subject. It would be patently false to say or suggest that Frye rejects religion. Frye is a a dialectical thinker and was quite capable of holding apparently antithetical positions and letting them grow into a more comprehensive view that includes them both. Yes, the history of the Christian religion, as Frye discusses in some detail in The Double Vision, is a ghastly one. He points out that religious communities have tended so often to resemble what he calls a “primitive society,” or “embryonic society,” “[o]ne in which the individual is thought of as primarily a funciton of the social group,” and hierarchical power structures and tight control of individuals are deemed necessary. Frye opposes this to what he calls a mature society– the likes of which, of course, we have never really seen–in which the “primary aim is to develop a genuine individuality in its members,” and “the structure of authority becomes a function of the individuals within it” (DV, 8). Churches and religious beliefs are always plagued by what Frye calls secondary or ideological concerns as opposed to human primary ones; and religious insitutions adapt the Gospel’s “myth to live by” to suit the power structures of their community and society. This does not prevent Frye from insisting at the same time that a mature society, if we are ever to see one, can only be one in which the individuals are spiritual people:

The New Testament sees the genuine human being as emerging from an embryonic state within nature and society into the fully human world of the individual, which is symbolized as a rebirth or second birth, in the phrase that Jesus used to Nicodemus. Naturally this rebirth cannot mean any separation from one’s natural and social context, except insofar as a greater maturity includes some knowledge of the conditioning that was formerly accepted uncritically. The genuine humanthus born is the soma pneumatikon, the spiritual body (I Corinthians 15:44). This phrase means that spiritual man is a body: the natural man or soma psychikon merely has one. The resurrection of the spiritual body is the completion of the kind of life the New Testament is talking about, and to the extent that any society contains spiritual people, to that extent it is a mature rather than a primitive society. (14)

As for science, precisely because it is a description of what is it cannot provide any spiritual vision of human ends. Ultimately, it has only a single, not a double vision of the world. It is not concerned, Frye would say, the way that art/literature and religion are. Art and literature and the Bible are about the world we want and the world we don’t want. They show us a world that makes human sense.That doesn’t concern science. Science and democracy have been great forces in changing and improving the world, and they have forced religious institutions to change for the better. They have separated church and state and diminished the secular and temporal power of religion, which is a necessary step to a much more open and non-dogmatic church, to a much greater openness of belief. For all Frye’s dissatisfaction with the United Church–where gays and lesbians are, by the way, fully accepted in every aspect and function of the church–he also praises it for its ability to remain open and improve:

I have been trying to suggest a basis for the openness of belief that is characteristic of the United Church. Many of you will still recall an article in a Canadian journal that emphasized this openness, and drew the conclusion that the United Church was now an ‘agnostic’ church. I think the writer was trying to be fair-minded, but his conclusion was nonsense: the United Church is agnostic only in the sense that it does not pretend to know what nobody actually ‘knows’ anyway. The article quoted a church member as asking. If a passage in Scripture fails to transform me, is it still true? The question was a central one, but it reminded me of a story told me by a late colleague who many years ago was lecturing on Milton’s view of the Trinity. He explained the difference between Athanasian and Arian positions, and how Milton, failing to find enough scriptural evidence for the Athanasian position, adopted a qualified or semi-Arian one. He was interrupted by a student who said impatiently, ‘But I want to know the truth about the Trinity.’ One may sympathize with the student, but trying to satisfy him is futile. What ‘the’ truth is, is not available to human beings in spiritual matters: the goal of our spiritual life is God, who is a spiritual Other, not a spiritual object, much less a conceptual object. That is why the Gospels keep reminding us how many listen and how few hear: truths of the gospel kind cannot be demonstrated except through personal example. As the seventeenth-century Quaker Isaac Penington said, every truth is substantial in its own place, but all truths are shadows except the last. The language that lifts us clear of the merely plausible and the merely credible is the language of the spirit; the language of the spirit is, Paul tells us, the language of love, and the language of love is the only language that we can be sure is spoken and understood by God. (20)

These are not the words of a man who rejects religion. They are the words of a religious visionary. Again, I highly recommend Bob Denham’s comprehensive treatment of this subject in Northrop Frye: Religious Visionary and Architect of the Spiritual World (U of Virginia P, 2004).

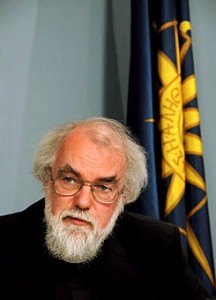

Rowan Williams, Frye, and the Church Prophetic

Rowan Williams is stepping down as Archbishop of Canterbury at the end of this year, and has taken the opportunity to remove the muzzle and openly attack David Cameron’s idea of Great Britain’s “big society.” He calls it

aspirational waffle designed to conceal a deeply damaging withdrawal of the state from its responsibilities to the most vulnerable. And if the big society is anything better than a slogan looking increasingly threadbare as we look at our society reeling under the impact of public spending cuts, then discussion on this subject has got to take on board some of those issues about what it is to be a citizen and where it is that we most deeply and helpfully acquire the resources of civic identity and dignity.

This critical and prophetic language reminds us of the genuine role of the church in society. Williams’ attack is especially resonant amid the scandal of shameless interest rate rigging at Barclays in Great Britain and of similar fraud and collusion by investment bankers in the United States. For more on the Barclay scandal, go here. For Matt Taibbi’s scathing article in Rolling Stone–his disgust is palpable–go here.

Williams’ book Faith in the Public Square will by published by Bloomsbury this September. Go here for more details. Here are a few more nuggets:

At the individual and the national level, we have to question what we mean by growth writes. The ability to produce more and more consumer goods (not to mention financial products) is in itself an entirely mechanical measure of wealth. It sets up a vicious cycle in which it is necessary all the time to create new demand for goods and thus new demands on a limited material environment for energy sources and raw materials. By the hectic inflation of demand it creates personal anxiety and rivalry. By systematically depleting the resources of the planet, it systematically destroys the basis for long-term wellbeing. In a nutshell, it is investing in the wrong things.

‘Big society’ rhetoric is all too often heard by many as aspirational waffle designed to conceal a deeply damaging withdrawal of the state from its responsibilities to the most vulnerable.

The significance of trying to shape public opinion within the Church is something quite different from an institutional programme on the part of the Church to impose its vision on everybody else.

Religion is seen by those who find it unacceptable as essentially an appeal to the will – decide to obey these presuppositions and to obey these commands. Religion in fact is consistently against coercion and institutionalised inequality and is committed to serious public debate about common good.

These remarks bring to mind so many passages in Frye, but his discussion in “The Church: Its Relation to Society” (1949), written at the beginning of the Cold War, is particularly prescient. The managerial or oligarchic dictatorship he describes here perfectly applies to the world of resurgent capitalism and “permanent war” we have been living in for decades now, ever since the Reagan and Thatcher “revolutions”:

It should be realized that Protestantism, like Catholicism, has had to struggle with a sacrilegious parody of itself, a struggle far harder to get one’s bearings in than the other. This parody is best described as laissez-faire, the industrial anarchism which represents the doctrine of individual liberty transferred from the society of love to the society of power.

After benefiting greatly from capitalism as long as it was dissolving the concretions of feudal. authority, Protestantism was considerably baffled when it turned demonic with the Industrial Revolution. The uninhibited grabbing of corruptible possessions, conceived not as a perennial fact of human nature but as a programme of human action, is the first open defiance of law and Gospel in modern history, for even the revolutionary Deism which preceded it made moral ideals out of Christian conceptions. As Ruskin points out in his trenchant polemic Unto This Last, the merchant under laissez-faire, unlike professional men, has no “calling,” no antecedent social reason for his existence.`’ Hence he cannot make any sacrifice of his natural will. From this fact two fallacies designed to rationalize laissez-faire have originated. One which goes back to Rousseau, is the conception of the “rights of man” as identical with the natural will of man. The other is the conception of history as the working out of the will of the natural society. The latter is sometimes called social Darwinism, because it misapplies Darwin’s biological theory to history, and, presents us with a vision of historical progress through the survival of the fit, the fit being those who fit the progress of laissez-faire by the possession of an unusually strong lust for power and profits. These two major fallacies have spawned a fruitful brood of minor ones, which we should take care, in talking about “liberalism,” to distinguish from those which are essential to a coherent Christian outlook.

The defences of laissez-faire offered today usually assume that the political form of it is democracy. This is nonsense: its political form is an oligarchic dictatorship. Every amelioration of labour conditions, every limitation of the power of monopolies, every effort to make the oligarchy responsible to the community as a whole, has been forced out of laissez-faire by democracy, which has played a consistently revolutionary role against it. . . . The essential identity of interest between the tendency to dictatorship in America and the achievement of it in Russia has been stated, though with some distortion of emphasis, in James Burnham’s well known book, The Managerial Revolution. How such a revolution could make its power absolute and permanent by a not-too-lethal form of permanent war is shown with great clarity in George Orwell’s terrible satire 1984, perhaps the definitive contemporary vision of hell. (CW 4, 263-64)

Celebrating Frye’s 100th Birthday

The Frye Festival is inviting everyone to a community celebration of Frye’s 100th birthday on July 13 in Moncton, at the Moncton Public Library. The Festival will unveil a bronze statue of Frye and announce the donation of Bob Denham’s Frye collection to the library. Bob will be saying a few words at the ceremony. You can read more about it here.

Also worth reading is a thoughtful piece on Frye by Richard Handler, “The Ideas Guy” at the CBC. You can find it here.

Frye in the Public Square, in the News and Elsewhere

A bronze sculpture of Frye is to be unveiled in Moncton on July 13. You can find an article about the unveiling at the CBC news site, here.

Also, on the 100th anniversary of his birth, the CBC is presenting its Ideas classic about Northrop Frye produced by David Cayley. If you haven’t heard the series, it is a must. Go here.

Finally, the following notice, courtesy of Bob Denham, is just one more instance of Frye’s reach as a public intellectual. The announcement, by Rev. Lesley Fox, is from a church in Winnipeg:

St. Andrew’s River Heights United Church welcomes you to a service celebrating the centenary of Northrop Frye’s birth, July 15, 10:30 a.m. Calling all U. of T. grads and admirers of Northrop Frye. We will share readings and reflections by Frye, Canada’s greatest philosopher and biblical literary critic.

Frye Alert: Book Shredder, Two New Books, and that Marxist Goof

Frye as book Nazi, here.

Two new books on Frye, Northrop Frye in Context by Diane Dubois (Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2012), here, and The Illustrated Frye by Garden Uthark, at Smashwords, here.

Terry Eagleton–“that Marxist goof from Linacre College”–pontificates on Frye and others, here, in The Daily Beast. Does Eagleton have any idea of the meaning of the word ‘authoritarian’? And how can we trust someone who describes Frederic Jameson as “a magnificent stylist”? Nonetheless, Frye made the list of his five favorite works of criticism. Actually six, since he slips in Kermode’s The Sense of an Ending in the preamble.