I

In one of the notebooks for his first Bible book Frye writes, “For at least 25 years I’ve been preoccupied by the notion of a key to all mythologies. I used to call this the ‘Druid analogy,’ & its components included Atlantis, reincarnation, cyclical symbolism. But surely that’s all in the Bible, & the Bible as is (Atlantis-flood, reincarnation = historical repetition, etc.). I think I have to make this book [The Great Code] the key to mythologies” (CW 13, 198). By “Druid analogy” Frye means the religious myths and rituals of natural religion in its most primitive forms. In another of his Bible notebooks he calls it the “pagan synthesis,” which is an analogy to the Biblical and Christian mythology.

In Fearful Symmetry Frye speaks of the myths of inspired bards of the ancient Druid civilization and the earlier myth of Atlantis, combined with the myths of the giant Albion and of Ymir, as containing “the key to all mythologies, or at least to the British and Biblical ones” (CW 14, 178).

In The “Third Book” Notebooks Frye writes that “Part One of this book, the Book of Luvah, to some extent recapitulates AC [Anatomy of Criticism] by taking the mythos of romance as the key to all mythical structure. This incorporates the epic & the sentimental-romance speculations that got squeezed out of AC. From here one could go either into Urizen, speculative mythology in metaphysics and religion, by way of Dante & the church’s thematic stasis of the Bible & the Druid analogy, or (as I favor now) into the applied mythology of contracts & Utopias (Tharmas) by way of Rousseau, William Morris, & various second-twist prose forms, including those of St. Augustine. (CW 9, 63)

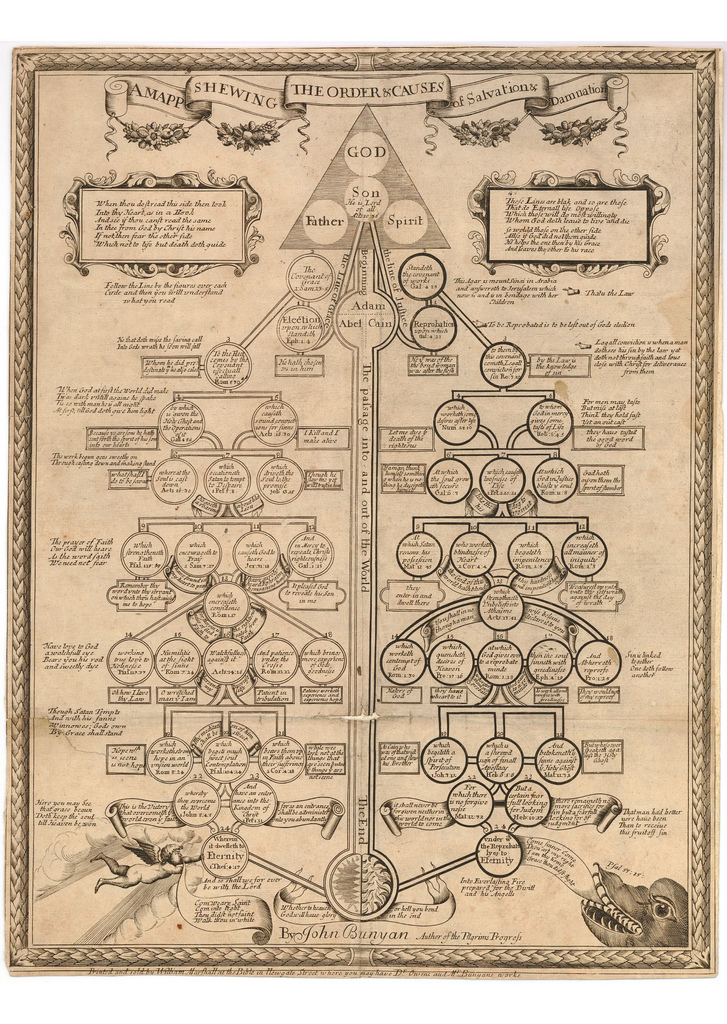

Frye made a valiant effort to provide a key to all mythology, trying to fit everything into what he called the Great Doodle, which was primarily his symbolic shorthand for the monomyth. Originally Frye conceived of the Great Doodle as “the cyclical quest of the hero” (CW 9, 214) or “the underlying form of all epics” (ibid., 241). But as he began to move away from strictly literary terms toward both religious language and the language of Greek myth and philosophy, another pattern developed, one with an east-west axis of Nous-Nomos and a north-south axis of Logos-Thanatos. At this point the Great Doodle took on an added significance, becoming a symbolic shorthand for what he called the narrative form of the Logos vision: “the circular journey of the Logos from Father to Spirit” (ibid., 260) or “the total cyclical journey of the incarnate Logos” (ibid., 201). But the Great Doodle is never merely a cycle. Its shape requires also the vertical axis mundi and the horizontal axis separating the world of innocence and experience. These, with their numerous variations, produce the four quadrants that are omnipresent in Frye’s diagrammatic way of thinking. In Notebook 7 he refers to the quadrants as part of the Lesser Doodle (par. 190), meaning only that the quadrants themselves are insufficient to establish the larger geometric design of the Great Doodle.

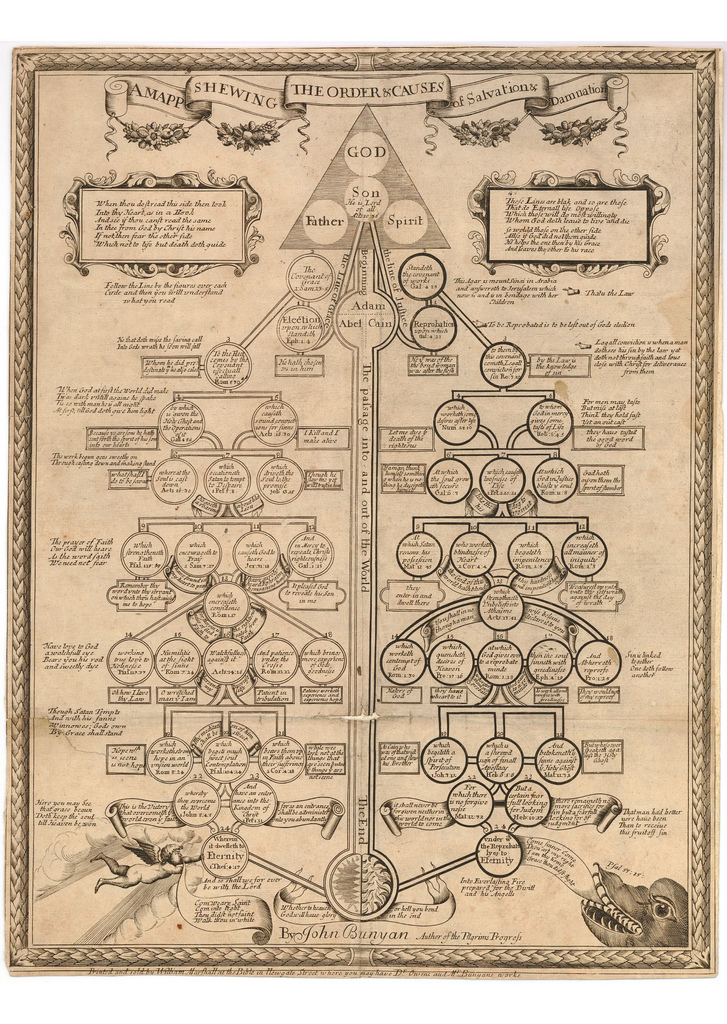

The Great Doodle has still further elaborations. In the extensive notes he made for his Norton Lectures at Harvard (The Secular Scripture) Frye remarks self-referentially that in book 14 of Longfellow’s Hiawatha the heroine “invents picture-writing, including the Great Doodle of Frye’s celebrated masterpieces” (Notes on Romance, weblog). The reference is to Hiawatha’s painting on birch-bark a series of symbolic and mystic images: the egg of the Great Spirit, the serpent of the Spirit of Evil, the circle of life and death, the straight line of the earth, and other ancestral totems in the great chain of being. Frye elaborates his Great Doodle in a similar way, the Hiawathan “shapes and figures” becoming for him points of epiphany at the circumference of the circle—what he twice refers to as beads on a string (CW 9, 241, 245). The beads are various topoi and loci along the circumferential string. They can be seen as stations where the questing hero stops in his journey (CW 5, 416) or as the cardinal points of a circle (CW 9, 147–8, 159, 177, 198, 200, 204, 249, 254). Frye even over lays one form of the Logos diagram with the eight trigrams of the I Ching, saying that they “can be connected with my Great Doodle” (ibid., 209), and one version of the Great Doodle recapitulates what he refers to throughout his notebooks as “the Revelation diagram” (CW 13, 193), the intricately designed chart that Frye passed out in his Bible course.

The Great Doodle, then, is a representation, though a hypothetical one, that contains the large schematic patterns in Frye’s memory theatre: the cyclical quest with its quadrants, cardinal, and epiphanic points; and the vertical ascent and descent movements along the chain of being or the axis mundi. It contains as well all of the lesser doodles that Frye creates to represent the diagrammatic structure of myth and metaphor and that he frames in the geometric language of gyre and vortex, centre and circumference.

There are other large frameworks that structure Frye’s imaginative universe, such as the eight-book fantasy—the ogdoad—that he invokes repeatedly throughout his career, or the Hermes-Eros-Adonis-Prometheus (HEAP) scheme that begins in Notebook 7 (late 1940s) and dominates the notebook landscape of Frye’s last decade. The ogdoad, which Michael Dolzani has definitively explained (“The Book of the Dead: A Skeleton Key to Northrop Frye’s Notebooks,” in Rereading Frye: The Published and Unpublished Works, ed. David Boyd and Imre Salusinszky [Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1999], 19–38), is fundamentally a conceptual key to Frye’s own work, though it is related in a slippery and often vague way to the Great Doodle. The HEAP scheme, in its half-dozen variations, is clearly used to define the quadrants of the Great Doodle, and there are countless other organizing devices, serving as Lesser Doodles, that Frye draws from alchemy, the zodiac, musical keys, colours, the chess board, the omnipresent “four kernels” (commandment, aphorism, oracle, and epiphany), the shape of the human body, Blake’s Zoas, Jung’s personality types, Bacon’s idols, the boxing of the compass by Plato and the Romantic poets, the greater arcana of the Tarot cards, the seven days of Creation, the three stages of religious awareness, numerological schemes, and so on.

All of these schematic formulations are a part of the key to all mythologies. But where did they come from? The came, of course, from Frye’s extensive knowledge of the literary tradition, the myths of literature arranging themselves in his expansive memory theater. But they also came from Frye’s reading of the mythographers.

Continue reading →