Lecture 10. December 9, 1947

The key ideas are ritual and myth. The active side of religion is ritual, the ceremony, the religious act. The myth side is the explanation of a ritual, the religious Word.

Ritual Act Ceremony King

Myth Word Doctrine Prophet

The basis of ritual is sacrifice, and this goes back to the idea of the substitute for the human sacrifice. The prophets come along with teaching so that the doctrine aspect is connected with the prophet. The pre-prophetic is ritual dependent upon the king. Now, the symbol becomes interpreted in mythic terms through the prophet.

DEVELOPMENT OF PROPHECY

The Psalms are the doctrine of the king in prophetic language. The prophets are concerned with the meaning of the ritual, an attempt to explain the true nature of the king. The king is the visible symbol of the larger human body, “society.” He is the social body united in one man. At certain points, the prophets have a special authority to appoint kings or heirs apparent.

The original motive for sacrifice is that the king’s energy is that of the tribe. In pre-exilic prophets you get the feeling that the old king is not good enough. Isaiah is one prophet who has got beyond that mental tailspin. For him the source of inspiration is consciousness; he is the trusted adviser of the king. Mixed up with what he says is a criticism of what is going on in history.

Isaiah Chap. 6, v. 8: “I heard the voice of the Lord, saying, Whom shall I send, and who will go for me? Then said I, Here I am; send me.” But no one wants to be a prophet. Isaiah asks, How long will it be? It’s no fun. In the same way, says Frye, the artist is wholly possessed by what he wants to say. Genius has nothing to do with sanctity or with whether or not the artist is good or bad. When he has genius, it possesses the whole of him and gives him the power to shape words as he wills. Yet the work of art itself is taking form; the artist releases what is being created. The sculptor sees the statue in the block of marble; it is not an act of will. There are always times when the artist, the prophet, is saying more than he knows.

Isaiah 7: 10–12: Ahaz represents conventional piety. “I will not ask, neither will I tempt the Lord.” This is the right answer, up to a point. But Isaiah takes up the idea of the “great sign of the Lord thy God.”

Isaiah speaks of the arrival of some new form of life, Immanuel, God with us. He speaks as if this is going to happen at once. In Chapter 8, Isaiah begets a child, and in the next chapter the arrival of this new life inspires him to say what is over Ahaz’s head, and over the whole situation, too. He talks of a new king on the throne of David. He is talking about the real king here. In Chap. 2 he talks of the “last days” and the spiritual king who will restore the age of paradise. Still, there is not any doctrine here yet, which you could not match outside the Christian religion.

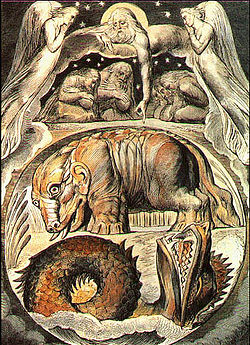

Micah makes the famous statement of the prophetic position against the sacrificial cult. Chap. 6, 6–8: the utter uselessness of ceremony in itself. Even human sacrifice will not attract God’s attention. There is the conception of the blood of a child as a redeeming scapegoat.

Will the Lord be pleased with thousands of rams, or with ten thousand rivers of oil? Shall I give my firstborn for my transgression, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul? What does the Lord require of thee but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God.

In Chap. 6, Hosea speaks a message of forgiveness, of the restoration of Israel through the love of God. “Come, let us return to the Lord.”

The pre-exilic prophets have the inspiration of the prophet and speak with consciousness. They condemn the moral evils of their community, the superstition, the mental attitude towards magic. But Amos is concerned with the paradox of the relation of God to his people. God has chosen one nation, and yet he is no respecter of persons. Amos denounces the neighbouring nations, and the audience loves it. He denounces Judah, the Southern Kingdom, and they still love it. Then, he turns and denounces the Israelites with the same voice. He acknowledges the uniformity of men, and yet retains the peculiar relation of God and Israel. To begin with, Israel means the larger human body, the concrete symbol of which is the King of Israel.

The prophets are led from the contemporary situation and the feeling that their own country is exceptional to the conception of the King of Israel as the source of authority in Israel and of its health and improvement. The prophets, therefore, become frank advisers of the king and will not flatter. The feeling merges that only the king is authority and God works through him. The pre-exilic prophets idealized the King of Israel as the Prince of Peace.

The paradox of a monotheistic state is seen in Amos where the hangover remains that God is concerned with the nation of Israel. This creates a difficulty that is not cleared up until the later prophets.