httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvE9EN4YPGM

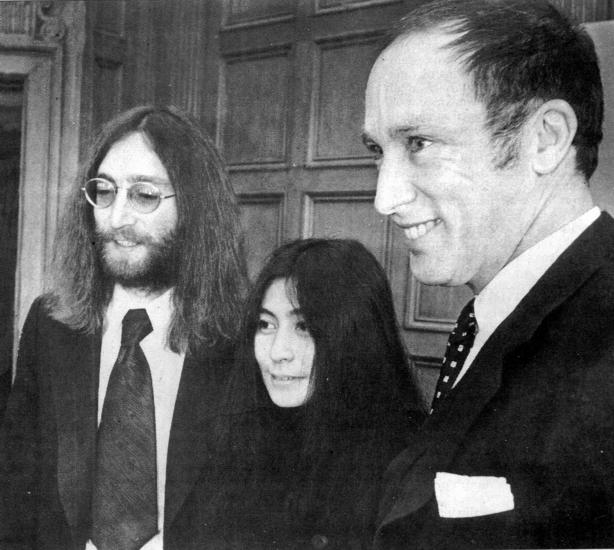

The Hour: Stephen Harper and U.S. style media control

Bob Denham`s article on Frye and Kierkegaard, recently published in our journal, shows the importance in Frye’s later work of the Danish philosopher’s emphasis, among other things, on concern. Frye first develops the idea in terms of the tension or dialectic between freedom and the myth of concern, as most fully worked out in The Critical Path. There it is argued that the imagery of literature is ultimately the language of concern. This insight becomes the basis of his later formulation of primary concerns in Words with Power, where he makes the distinction between primary human concerns and secondary or ideological ones. One of the books of Frye`s now famous Ogdoad (famous at least among amateurs of Frye) is entitled Liberal, and it strikes me that this indicates another source of Frye`s concept of concern, and in particular his formulation of the distinction between primary and secondary concerns.

It would be of great interest to examine this idea of primary concerns as a genuine contribution to socio-political thought, specifically liberal and social democratic thought. Certainly there have been essays touching on the liberal humanism of Frye`s critical position, or what I would prefer to call his critical “vision.” It is often a stance he has been attacked for. More sympathetically, Graham Good, for example, has a particularly discerning article on the subject. Years ago I presented at a conference a very preliminary stab at such an examination, but I have not had the opportunity yet to follow it up. Involved in such a study would have to be a comparison, ultimately, of Frye`s concept of primary concerns with such theories as John Rawl’s idea of basic goods, and even more with Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum’s idea of basic human capabilities. These ideas are a different way of talking about human rights and are very close to Frye`s primary concerns, focusing as they do on those universal human needs and wishes that can be regarded as essential to the dignity and fulfillment of every human individual. It is worth emphasizing that it is this kind of thinking in the liberal and social democratic tradition that has given us, among other things: universal health care (now severely threatened); legal access to abortion; gay marriage; serious efforts to ensure gender equality and protect minority rights; a less punitive system of law and order aimed at restoring the incarcerated to reentering and contributing to society; a more welcoming policy to refugees fleeing persecution or unimaginable hardship in their own countries. The list could go on.

These great benefits have derived from an often invisible or inarticulate social norm, not in the normative sense, but as an ideal the departure from which makes irony and the grotesque ironic and grotesque. This ideal is “the vision of a more sensible society,” of a world that actually makes human sense. Such a vision works outside literature among individuals in their daily lives and workplaces, giving meaning to their work and actions beyond any need for a pay-cheque. As Frye writes: “one can hardly imagine, say, doctors or social workers unmotivated by some vision of a healthier or freer society than the one they see around them.” The same could be said of any member of society who contributes in a meaningful way, who has, in other words, a social function, this being, as Frye views it, the real significance of the democratic ideal of equality. In a true democracy, everyone is potentially a member of an elite, and no-one`s social function is more worthy of respect than another’s.

This idea of a social vision, ultimately the vision of a world of fulfilled primary concerns, is particularly useful in defining the issues we face in the current Canadian election campaigns. Any genuine social vision of a healthier or freer society is precisely what the program of Stephen Harper and the Conservatives are devoid of. It is telling that Harper almost always speaks of the economy, never of society. It is as if it doesn’t even occur to him. Contrary, however, to the famous tag-line, it’s not the economy, stupid: it’s society.