Please check out Dawn Arnold’s new Frye Festival blog here.

Category Archives: Frye Festival

Frye Festival Newsletter

You can see February’s Frye Festival Newsletter here.

Frye Festival Newsletter

December’s Frye Festival Newsletter here.

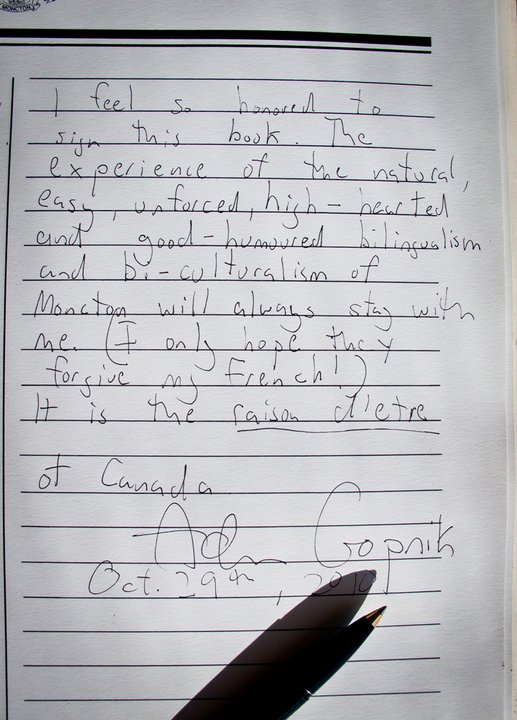

Adam Gopnik Thanks Moncton

Dawn Arnold: New York, Paris, Moncton!

The Frye Festival had the great good fortune of welcoming New York Times bestselling author and prolific New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik to its fall Community Read on October 29th. Adam is perfect for a Community Read / un livre, une communauté because he is bilingual and he has a very popular book that is available in paperback in both English and French (Paris to the Moon). He had been on our programming committee’s radar for years, but he is a busy guy! I met him a couple of years ago in New York at the PEN Writers Festival (I wasn’t technically stalking him, but close!) and of course I invited him again. Through Ed Lemond’s persistence, the assistance of lots of authors who had been through the Festival over the years who knew Adam, and the financial clout of Université de Moncton’s Alumni Association, we finally landed him.

In preparation for Adam’s visit, I pulled out John Ayre’s biography of Frye (as I often do) and sought some insight. It was fun to see what a big role the New Yorker played in Frye’s life, especially while he was in Europe.

When Frye was studying at Oxford, he was dependent upon Helen to send him “supplies” from North America. From Ayre’s biography:

“Nothing annoyed him (Frye) immediately more however, than Helen’s apparent failure to send along promised copies of the New Yorker. In furious block lettering he admonished her “WHEN THE HELL ARE YOU GOING TO COME THROUGH WITH SOME NEW YORKERS?” Given Frye’s seemingly bottomless taste for esoteric works, this voracious desire for copies of America’s quintessential upper-middle-class weekly with its cartoons and satire by Thurber and White appeared mysterious. But within the context of his misery at Oxford, it represented a life-line to an urbane North American perspective which Frye desperately needed.”

The New Yorker obviously still has tremendous pull all around the world and Moncton is no different. Nearly 100 people (some of whom I have never seen before at Frye events) came out to meet Adam. And what an incredibly gracious and professional person he is! Adam had only been in town for about two hours when we had him on stage and already he was waxing philosophical about the incredible linguistic fluency he was enjoying all around him. He had an open and freewheeling conversation with Janique LeBlanc, a local journalist for Radio-Canada who had just returned from nine years in Switzerland. Adam is a gifted storyteller and one simple question could lead in many different directions. We were treated to so many insights into his life in Paris, raising a child in Paris, the fundamental differences between American and French culture (it all comes down to tomatoes!) and of course some great anecdotes about the New Yorker. His hopeful message was that 25 years ago when he began his career, there were many people who believed that the word was dead and that images would take over. Despite our age of sound bites and blog posts, the New Yorker is still very much alive. The one hour conversation was simply not enough, but after a few great questions from the floor, Adam chatted with everyone at a beautiful reception (and he even signed the Mayor’s guest book, writing a full-page article!).

Adam Gopnik at Frye Festival Community Read

From Moncton’s Times & Transcript

Adam Gopnik to make appearance on Oct. 29 at city hall

A New York Times bestselling author will appear in Moncton later this month during the Frye Festival’s Fall Community Read.

Adam Gopnik, a writer for The New Yorker, will appear in the lobby of Moncton City Hall on Friday, Oct. 29 from 5 to 7 p.m.

The event will be followed by a reception with refreshments.

Born in Philadelphia but raised in Montreal, Gopnik left the familiarities of New York City in 1995 for the charm of Paris. His wife and their infant son went along, and for five years they tried to catch on to the quirks of French culture. Gopnik recorded his experiences, frustrations and delights in his “Paris Journal” for The New Yorker, which won him awards.

A collection of the Paris Journals was published in 2000 by Random House as “Paris to the Moon.”

“We encourage everyone to come discover this bestselling and award-winning author,” says Frye Festival executive director Danielle LeBlanc. “The way Gopnik relates the meeting of two cultures in Paris to the Moon fittingly reflects the realities of our daily lives here in Moncton.”

Those who want to read some of Gopnik’s work before the event can go to www.frye.ca.

A reading guide with information on the author and chapter summaries is also available on the website.

Admission to the event is “pay what you can,” with donations requested.

The Frye Festival’s Community Read series presents bilingual authors whose books are available in translation. The aim is to encourage dialogue between the linguistic communities by rallying them around one author and one book.

Adam Gopnik in Moncton

Alberto Manguel: “The Blind Bookkeeper”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y8zyK3DtXxQ

Manguel giving the Fitzi-Continis Lecture, “Borges and the Impossibility of Writing,” at Yale University, February 3, 2010

Toro Magazine has a review of Alberto Manguel‘s The Blind Bookkeeper (or Why Homer Must Be Blind) — an expansion of his Antonine Maillet – Northrop Frye Lecture at this year’s Frye Festival in Moncton — and which begins with Frye’s almost unbelievably prescient unfinished 1943 essay, “The Present Condition of the World” (recently cited here and here).

THE BLIND BOOKKEEPER (or Why Homer Must Be Blind)

By Alberto Manguel

Goose Lane Editions

$14.95

80 pagesPOSTED BY: Salvatore Difalco

Which brings me to the last of my three recommended reads: Alberto Manguel’s elegant bijou of concision, The Blind Bookkeeper, a bilingual transcription of The Antonine Maillet – Northrop Frye Lecture delivered at The University of Moncton by Manguel this past April. An unfinished paper Northrop Frye wrote in 1943 on “the state of the world,” and his ideas of what to expect after the end of the war and the role that literature might play in a time of peace, act as the starting point for Manguel’s moving meditation on the complex and complimentary roles of writer and reader throughout history. Frye’s essay, prescient in 1943, has never been more relevant than today, given the current spiritual and cultural bankruptcy of our neighbours to the south, with their toxic mix of demented evangelism, material superabundance, and pure aggression.

In considering the state of reading and writing today, against the backdrop of ongoing global conflict, Manguel turns to the blind Homer, the archetype of the poet who can see into the future through his knowledge of the past, as inspiration and guide. And with Homer at his side, and Northrop Frye on his heels, he charts a history of war in relation to literature (or, conversely, a history of literature in relation to war). But this overly simplifies what amounts to a stunning tour de force by Manguel. The title of his lecture, hinging on the word bookkeeper, is telling. What´s clear is that Manguel, a bibliophile in every sense of the word, who as a youth in his native Argentina spent four years reading to and hanging out with that meta-bibliophile Jose Louis Borges, loves literature and books, and that love permeates and lights up every sentence.

“Literature is a collaborative effort, not as editors and writing schools will have it, but as readers and writers have known from the very first line of verse ever set down in clay. A poet fashions out of words something that ends with the last full stop and comes to life again with its first reader’s eye. But that eye must be a particular eye, an eye not distracted by baubles and mirrors, concentrated instead on the bodily assimilation of the words, reading both to digest a book and be digested by it. ‘Books,’ Frye once noted, ‘are to be lived in.’” p.27)

Which brings me back to my initial complaint about the length of the books being offered for review this autumn, and how the times, distracted, overburdened, demand, along with relevance, concision. That being said, I’m not against long books, per se, but I do detest being told that these current, bloated offerings, written by relative unknowns, are necessary, groundbreaking, brilliant, and all but worthy of being canonized. Given the entire history of literature, and the existence of Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Joyce, Borges, et al, publishers and publicists alike should step out from their fairylands, and maybe hire a few competent editors to slough off all the dead skin they’re carrying around.

Frye Sculpture: Down to the Wire

The Frye sculpture proposal remains very much alive in third place — the top two finishers receive a $25,000 prize. Voting ends tomorrow. Vote today and tomorrow here.