Cross-posted in the Robert D. Denham Library

In Mahayana Buddhism, bardo, a concept that dates back to the second century, is the in-between state, the period that connects the death of individuals with their following rebirth. The word literally means “between” (bar) “two” (do). The Bardo Thödol, or “Liberation through Hearing in the In-Between State,” distinguishes six bardos, the first three having to do with the suspended states of birth, dream, and meditation and the last three with the forty-nine-day process of death and rebirth. In The Tibetan Book of the Dead, which is the principal source for Frye’s speculations on bardo, a priest reads the book into the ear of the dead person. The focus is on the second three in-between states or periods: the bardo of the moment of death, when a dazzling white light manifests itself; the bardo of supreme reality, in which five colorful lights appear in the form of mandalas; and the bardo of becoming, characterized by less-brilliant light. The first of these, Chikhai bardo, is the period of ego loss; the second, Chonyid bardo, is the period of hallucinations; and the third, Sidpa bardo, is the period of reentry.

In Frye’s Bible lectures he mentions the bardo in connection with the issue of whether one can be released from various projections and repressions and so escape from the wheel of reincarnation, or at least have the possibility of escaping next time around if one will only be attentive. There, he said,

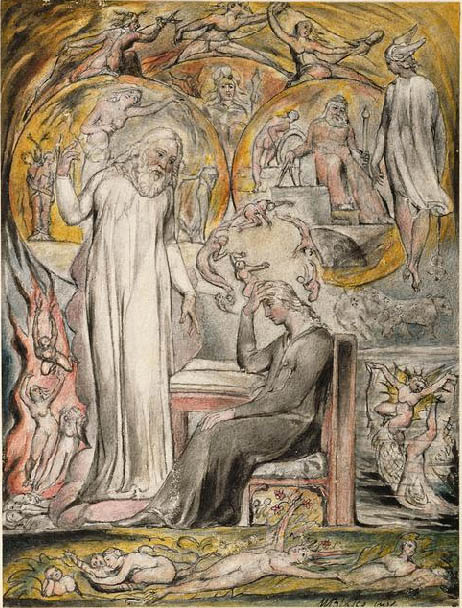

The word “apocalypse,” the name of the last book of the Bible, is the Greek word for revelation. That is why the book is called Revelation in English translation, and what John at Patmos sees in the book is a panorama of certain things in human experience taking on different forms. There is an analogy which seems to be a fairly useful one in the Oriental scripture known as The Tibetan Book of the Dead. When a man is dying, a priest comes to his house, and when the man dies, the priest starts reading the Book of the Dead into his ear, because the corpse is assumed to be able to hear the reading and to be guided by what is said. The priest explains to the corpse that he is going to have a progression of visions, first of peaceful deities and then of wrathful deities, and that he is to realize that these are simply his own repressed thoughts and images coming to the surface because they have been released by death; and that if he could only understand that they are coming out of his mind, he could be delivered from their power, because it is really his own power. lt is also assumed that practically every corpse to whom this book is read will be too stupid to understand what’s going on, and will go on from one blunder to another until finally he wakes up in the world again: because the assumption behind it is one of reincarnation. [CW 13, 587–88]

Otherwise, in his published writing Frye refers to bardo infrequently––once in The Great Code, once in A Study of English Romanticism, once in “The Journey as Metaphor,” and twice in “Yeats and the Language of Symbolism.” In his notebooks and diaries, however, the word “bardo” appears more than one hundred times, and Frye’s own copy of The Tibetan Book of the Dead contains some 240 annotations. In Northrop Frye: Religious Visionary and Architect of the Spiritual World I point out that Frye almost always uses “bardo” in a telic sense: it represents a stage toward the end of the quest, and it is related to such ideas as epiphany, resurrection, recognition, and apocalypse––ideas that are omnipresent in Frye’s writings. But his understanding of bardo warrants further study.

The following entries represent, I think, all of the places in Frye’s “unpublished” writing (now a part of the Collected Works), where the word “bardo” appears. The “published” references are at the end. The annotations have been omitted. All material within square brackets is an editorial addition.