Re: Bob Denham’s “Frye’s Superlatives“

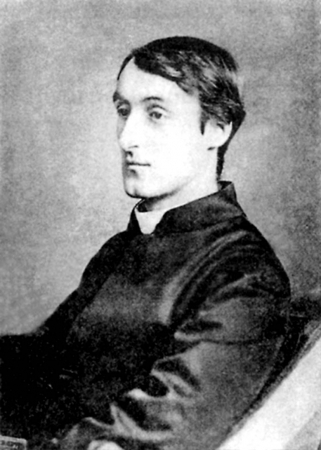

“If Hopkins could only have got rid of his silly moral anxieties, his perpetually calling Goethe a rascal and Whitman a scoundrel and the like, he’d have been the greatest critic of his time.” [RN, 325]

Thanks, Bob, for an intriguing post.

When I worked on my article on “Frye and Catholicism,” the Notebooks on Romance had not been published (in fact, the article and Notebooks both appeared in 2004). It would have been nice to have been able to use the following passage, one of the most interesting statements Frye makes about Catholicism:

“By the way, I must get rid of my fear of Catholicism long enough to distinguish the kinds of it that are purely Fascist & therefore factional (the paranomasia of national & natural religion as the Satanic analogy should be noted) from a cosmopolitan & liberal residue. In Dante the former is Antichrist, the Avignon Pope. In Dickens there is a real catholicity of the latter kind.” (RN 28)

I wonder whether Frye didn’t feel a degree of anxiety about the fact that some of the writers he admired most, and who play a significant role in his theory of literature, were Catholic Christians, like Dante, Hopkins or T. S. Eliot.

The reference to Hopkins’s “silly moral anxieties” recalls a number of comments he makes about Chesterton and Ruskin (I intend to pursue the former in a future post). Gerard Manley Hopkins as the greatest critic (potentially) of his time is a truly surprising statement. Hopkins certainly makes some very influential and significant comments concerning his sacramental theory of poetry. Concepts such as “inscape” give rise to many fascinating classroom discussions, in my experience. But Hopkins was also a dreamer, someone who concocted large intellectual and literary projects that he was never able to bring to fruition (rather like Coleridge in that respect). It is hard to imagine him producing enough significant work to be a truly great critic. As for calling Whitman a scoundrel, he nevertheless registered his influence in his own poetry, I think.

A major critical influence on Frye was Oscar Wilde, author of “two almost unreasonably brilliant” critical dialogues (NFR 87), “The Critic as Artist” and “The Decay of Lying.” The conclusion of Wilde’s De Profundis is another place where he anticipates Frye’s ideas. My teacher at the University of Toronto, W. David Shaw, argued that by the end of De Profundis the regimentation of time and space in Reading Gaol have become metaphors for the categories of time and space in general, which can be overcome by the poetic imagination. A couple of years ago I was inspired by a comment Michael Dolzani made in a CBC Ideas programme about Frye to explore the affinities between Frye and Wilde. Both critics shared a preference for the idea of literature as a visionary new creation to the idea of literature holding the mirror up to nature.

It’s interesting that there has been some lively recent scholarship on Wilde and Catholicism. (I have myself shocked several people, at least some of them evangelical Christians, by including Wilde in a course on the Catholic tradition in English literature. I like to tell them the story about how he was baptized three times: the details are in Richard Ellman’s biography).

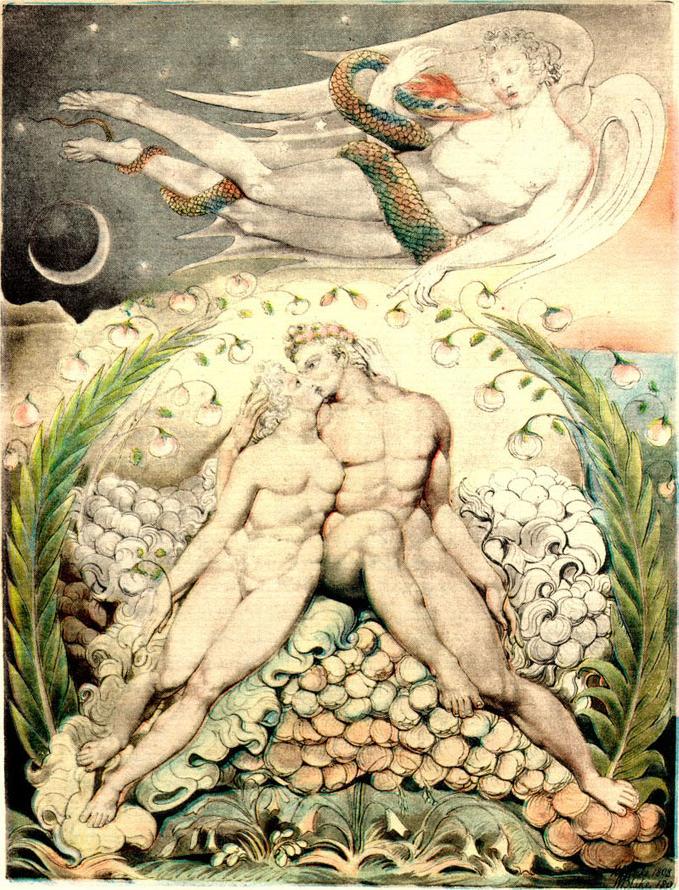

I wonder who was the greatest of all English critics of any period for Frye, to indulge in some more “literary chit-chat,” if not “sonorous nonsense.” William Blake, who was his preceptor in all things? Frye’s marginalia seem to emulate Blake’s sometimes. Sir Philip Sidney, Protestant humanist and intellectual, might be another candidate (with his visionary golden world as opposed to the brazen world of nature). And Frye, of course, uses Sidney and Aristotle as key elements in his own theory of literature in the Anatomy.