Mervyn Nicholson, in the first of what promises to be a series, considers what makes Frye different. In this installment: Desire.

Frye is unusual as a literary-cultural critic-theorist in many, many ways. But one way that I find fascinating is Frye’s attitude toward human desire. Frye was a champion of human desire, as was his mentor, William Blake.

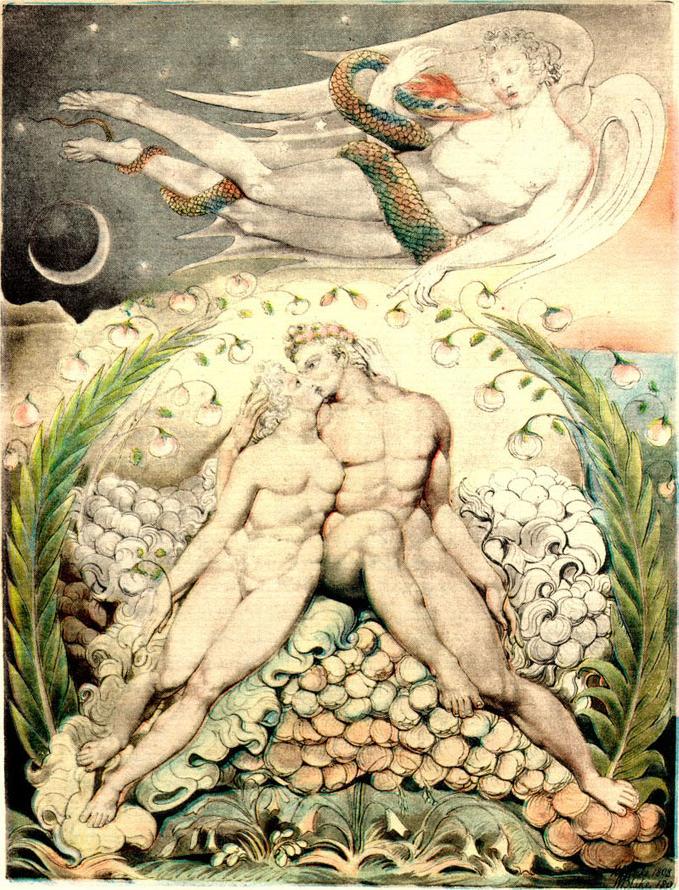

But in this Frye, like Blake, is opposed to practically the entire history of culture, a history of hostility to desire. For Christianity, human desire is corrupted by the Fall, and can not be trusted. What is needed is obedience to authority; by contrast, human desire is in fundamental conflict with the requirements of obedience. The problem began with Adam and Eve who disobeyed, followed desire, and thus brought death into the world along with everything else that is bad, from mosquitoes to forest fires.

Christianity is not alone in distrusting and even disowning human desire. Philosophy has rarely had much respect for desire, which it typically puts somewhere in the basement of human faculties, right next to if not actually in the trash barrel, along with illusion, opinion, prejudice, and other detritus of consciousness. Post-structuralism in its core form of deconstruction maintains the same hostility to desire. Deconstruction as theorized by Jacques Derrida and practiced for example by Paul de Man, has for its keynote a conviction that desire equates with the unreal. An entire attitude is summed up in the dictum of Paul de Man: “Metaphor is error because it feigns to believe in its own referential meaning.” Metaphor and metaphoric thought is indistinguishable from deception, above all self-deception. Political economy—economics—has stressed the dangers of human desire, from at least Thomas Malthus’s Essay on Population on. The standard economics text begins with the premise that “economics is the science of scarcity”: there isn’t enough to go around. In the conflict between what we want and what we can have, necessity always wins. People must keep desire in check, or disaster will result.

Freud, despite his liberal views, is consistent with traditional attitudes. The entire psychoanalytic tradition is deeply mistrustful of desire. What you want but cannot have, you then create imaginary satisfactions for. For example, we fear to die, so we “make up” an afterlife, an imaginary compensation. This view of desire, as the origin of illusion, is fundamental to Freud, who lays it out with particular clarity in The Future of an Illusion. The test of an illusion is whether it is a wish fulfilment. “What is characteristic of illusions is that they are derived from human wishes,” Freud explains. “Thus we call a belief an illusion when a wish-fulfilment is a prominent factor in its motivation . . . the illusion itself sets no store by verification.” Dreams are of course illusory satisfactions, as Freud argues in The Interpretation of Dreams: dreams are all wish-fulfilments. But wish-fulfilments are by definition illusory satisfactions. This is also a theme of the revisionist psychoanalysis of Jacques Lacan, as well as of Melanie Klein and the “object relations” school of psychology. Make-believe compensates for loss and alleviates frustration. But it is still make-believe, and make-believe causes problems. Similarly, Freud insisted that fantasies, conscious and unconscious, cause neurosis—fantasies so endemic in fallible human nature that they begin in infancy. In Freud’s view, infants fantasize pretty weird things because they want weird things, and that weird wanting affects them for the rest of their lives.—our lives, in fact

Frye is so different from this tradition! he insists throughout his writing and throughout his career that human desire is good, that it is a guide, that the distinction between what we want and what we do not want — as Frye himself argues in The Educated Imagination — is the basic axis of existence and of civilization itself. Literature is a product of human desire, as is all of civilization. By showing us what we want and what we do not want, literature functions as a guide to ourselves and a means of evaluating the society we have created and that we also have the power to change. For Frye, desire is who we really are.

I agree that Frye departs from the main traditions of Christian orthodoxy in some significant ways (though how significantly depends on the way one defines those traditions, hardly something on which there is general agreement!) But I think that the idea of original sin is often present in his thought – that is, the idea that human beings are, in Newman’s words, “implicated in some terrible aboriginal calamity.”

Frye identifies the primary concerns, which are our desires for such things as food, shelter, and companionship. But it is only in the imagined world of literature that such concerns are not overwhelmed by the secondary concerns of ideology. And even literary works have their inevitable ideological dimension, as in Frye’s favourite example of _Henry V_.

Frye sometimes refers to human beings as “psychotic apes”! I think he agrees with Freud that civilization is fragile, doesn’t occur very often, and exists to regulate our desires, which otherwise would be boundless. If there isn’t enough to go around in terms of material goods, how much more is that true in terms of prestige and status.

Freud’s ideas, especially as expressed in _Civilization and Its Discontents_, seem to me based on a fairly accurate perception about the way that desire has to be controlled and regulated for civilization to exist. And Frye would seem to agree with that in his comments about human beings in society. Somewhere he comments on how the sounds of children at play are far from the pastoral innocence of sentimental imaginings. When he talks about discipline as the way to freedom (as in learning to play the piano), he sometimes sounds like Milton talking about “right reason.”

Thus while Frye rejected what he saw as the neurotic obsessions of some forms of Christianity (e.g., anxieties about drinking alcohol in the tradition in which he was raised), I see him as continuing many of the themes and concerns of Christian humanism.

But I readily admit to an inadequate knowledge of Blake, and of the side of Frye which read what Bob Denham refers to as his “kook books,” and I’m sure a much more unorthodox, antinomian Frye exists as well as the figure I am constructing here. I suppose the real question is what one foregrounds in one’s reading of Frye’s work.

I once argued with a Frye scholar about original sin. I claimed that Frye was the biggest apologist for the doctrine of original sin that I knew, and I was told I was completely mistaken, that Frye thought the doctrine was one of the worst ideas ever invented.

What I realized after that conversation was that Frye insists (like Blake) on the reality of the Fall, but never equates the Fall with original sin. As Frye puts it in Fearful Symmetry, the fall and creation are the same event. For Frye, it is self-evident that we live in a fallen world, and it is hard for me to imagine a sane person who would not agree with him. But that falleness is not the result of human sin, but rather the matrix of human sin. There is no primordial guilt for Frye. I think Frye in general had little interest in guilt, and that is not because he denied the reality of sin, but like Blake, he accepted the reality of sin but denied the reality of Judgement (this is probably his biggest departure from orthodoxy).

This is the impression I have from my reading of Frye, but I’d very much like to be corrected or hear other views.

As for desire, it seems to me that his abandonment of the term, in favour of “concern,” was an attempt at greater precision, but it seems to correspond with a loss of some of the explosive energy we see in his Blake book.

But even in Fearful Symmetry, I don’t think desire is seen as a good in itself. Rather, what is good is action, and action is conceived of as desire seeking form. And there are even more caveats. If the desire is to frustrate or impede action, the resulting action is not worthy of the name. And desire that is not acted upon is pestilent.

And also it is specifically the desire feeding creation that is good. Any desire for a created thing is “the cry of a mistaken soul”. Even the erotic delights of Beulah are temporary and must give way either to creation or alienation.