I’d like to add to the recent discussion thread on Harold Bloom

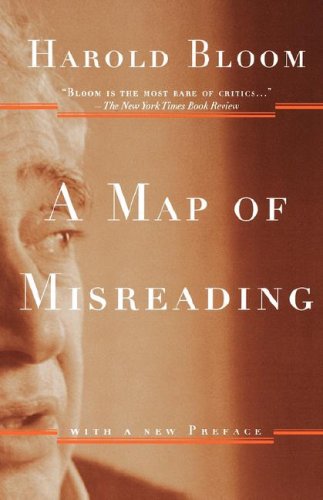

The reason Bloom, in this interview, does not mention Frye in his list of “my greatest influences” is that Frye’s influence ended when Bloom had a nervous breakdown and began to write nonsense after deciding that literature was primarily “based upon agonistic competition,” as he puts it in the interview. It is all about the Oedipus complex and castration anxiety. It is all about which writers are greater, stronger, more powerful than others: in other words, which writers Bloom identifies with, and which ones he dismisses. His judgment of Poe is a perfect instance (see his attack on Poe in the New York Review of Books, “Inescapable Poe”): “Poe’s survival raises perpetually the issue whether literary merit and canonical status necessarily go together. I can think of no other American writer, down to this moment, at once so inescapable and so dubious.” He ridicules, for example, the overwrought prose style of the narrators in Poe’s great tales, a style that is in fact carefully attuned to the states of mind of the characters, who are often criminally insane or on the threshold of consciousness. It is as if a critic were to ridicule Mark Twain’s prose style in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn because the narrator writes ungrammatically and uses cuss words. In contrast, Frye regarded Poe as a literary genius.

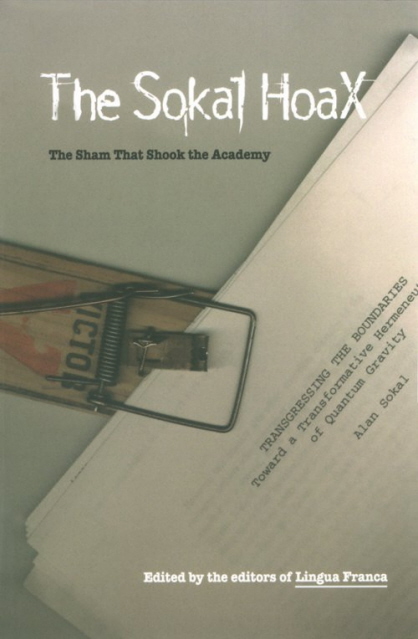

Here is how Bloom sums up his ‘literary theory’ of influence: ”I use the Shakespearean term ‘misprision,’ which is a kind of deliberate creativeness. The later work overturns an earlier work in order to get free of it. The new poem, new story, new drama or new novel is a creative misreading of the work that engendered it.” Literature is thus reduced to a Nietzschean or Oedipal struggle between grand creative minds. When literature is not that, for Bloom, it is the “touchstone theory” all over again: as he quotes Curtius, literature is “a reservoir of spiritual energies through which we can flavour and ennoble our present-day life.” Is this really what literature is all about? A kind of aesthetic and spiritual gilding of our prosperous middle-class life? Such an ennobling influence, however, doesn’t seem to have had much effect on Bloom. Read the interview, which starts, not very nobly, with a rant about attacks on the canon and his “desperate” but futile attempts to defend the curriculum of great books against the invasion of feminist Visigoths:

I do not give in to political considerations, however they mask themselves. All this business about gender, social class, sexual orientation and skin pigmentation is nonsense. I’m 81. I’m not prepared to temporise any more. I’ve been prophesying like Jeremiah since 1968, warning the profession that it was destroying itself. And it has.

It is interesting that Bloom began his jeremiad around the same time he broke with Frye. That’s over forty years, I guess, of not temporising. But this harangue is no better than Lynne Cheney (“not for me”) and Alan Bloom in the Closing of the American Mind. It is the tedious and angry voice of a reactionary. Frye was certainly concerned about the ascendency of ideological criticism but he countered it with a defence of the liberality and autonomy of imaginative culture. He did not speak contemptuously (“all this business about gender, etc.”), and he never whined and railed. He did not dismiss other people’s genuine concerns, even when he thought they were misguided; he tried to engage them, with as much graciousness as possible. And then there is Bloom’s vanity, transparent throughout, and the maudlin sentiment, the name-dropping, the emphasis on close “personal” friends (“Those are the five books. Four of them are by personal friends, and one is by someone I corresponded with.”), the nauseating idolatry of genius, and the wheedling allusions to the enormous number of enormous books he has written, one volume after another dedicated to the memory of his own opinions.

As Frye points out,

Criticism founded on comparative values falls into two main divisions, according to where the work of art is regarded as a product or as a possession. The former develops biographical criticism, which relates the work of art primarily to the man who wrote it. . . . Biographical criticism concerns itself largely with comparative questions of greatness and personal authority. It regards the poem as the oratory of its creator, and it feels most secure when it knows of a definite, and preferably heroic, personality behind the poetry. If it cannot find such a personalty, it may try to project one of out of rhetorical ectoplasm, as Carlyle does in his essay on Shakespeare as a ‘heroic’ poet.

Bloom is not a serious critic or a serious literary theorist. He has no critical theory to speak of. He is an extremely well-read man with an inflated ego and a photographic memory. It is no accident that he feels the need to present such a personal list of great works of literary scholarship, a list of the works that most influenced him, not the profession, as the interviewer requested. It is exactly what he does with literature. His books, as he says himself, reveal a man “desperately trying to battle for canonical standards.” It is the critic as judge, as maker of value-judgments. Frye, of course, demonstrated the perversity of such a basis for literary study in his polemical introduction to Anatomy; it is an essay that is always worth reading again, because value-judgments, like bedbugs, seem impossible to eradicate: they just keep coming back in new mutations. Enough of Bloom. Frye has already summed it up: “The odious comparisons of greatness, then, may be left to take care of themselves, for even when we feel obliged to assent to them they are still only unproductive platitudes.”