Le Hire, Job Restored, 1648

Lecture 19. February 24, 1948

THE SEARCH FOR WISDOM

There are concentric spheres in the Book of Job. The inner sphere is a morality play with virtue and vice in argument with friends. From the deadlock of the argument to the end of Elihu’s speech is another sphere. The still-wider concentric sphere is that of a divine comedy—God watching Job and then restores him. There are ironic overtones to the “tragic” story.

The same concentric pattern is in the life of Jesus. The active Jesus, the teacher and healer, is the kernel of the story. His tragedy is another sphere. Then comes the divine comedy of redemption. King Lear is a morality play at heart with the good people against the bad. Outside that is tragedy which is not moral because Cordelia dies. Around that is the adumbration of the comedy, of a man who attempted to find divinity in kingship but finds it only in suffering humanity.

In the last chapter, verse 8, Job becomes the redeemer of his friends. “And my servant Job will pray for you.” But Job has suffered too much for the restoration of his flocks and children to be the answer to his problem. Job’s is a personal search for wisdom.

What the restoration of his children represent are the symbols of that new wisdom.

In the Old Testament, the histories focus on a king. In the prophecies, they focus on the watcher as opposed to the doer of the New Testament. Job is the third division of the Old Testament, the Wisdom books, like Solomon, Proverbs and Ecclesiastes. What takes place is a personal form of wisdom.

Comedy will not come with restoration. Too much has happened. God is too responsible. Job is not hankering after his goods and children but the reality of which they are symbols; this he identifies with wisdom. He begins the search for wisdom with “why did God do this to me?” This expands into “what is God?” The search for God is the search for wisdom. And God is inside Job.

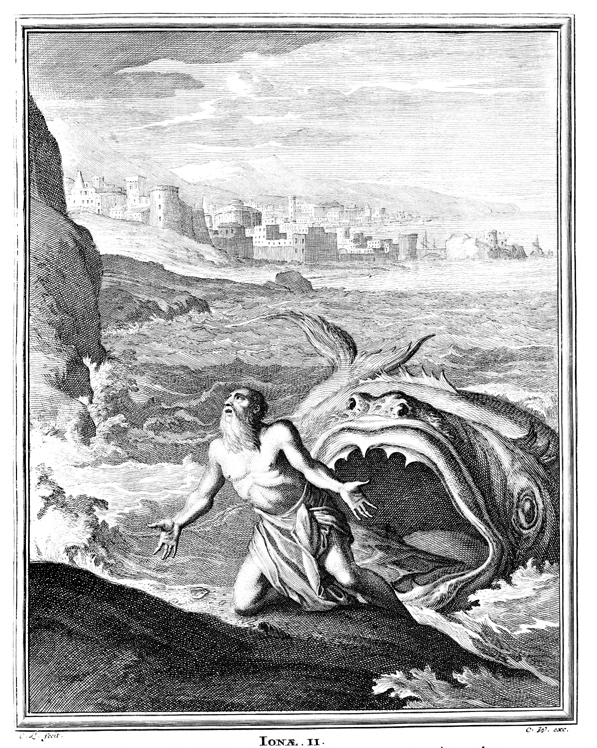

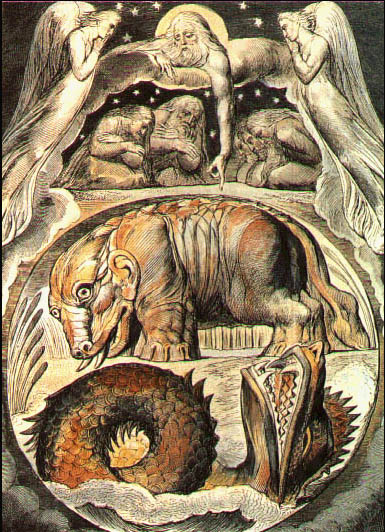

In Chapter 10, God describes Behemoth and in Chapter 14, Leviathan. The chief point is this description is the phrase “he is king over all the children of pride.” Why is this so significant? Why does it enlighten Job so that he says “now my eye sees thee.” We would expect God to lead him to Satan, but he leads him to Leviathan. Satan and Leviathan are the same person. Satan stands for the tyranny of nature and man. Job sees the form of his tragedy as a monster, that is, now he can see it because he has been coughed out of the belly of Leviathan.

Job is detached from a world of the tyranny of man and nature. He has found a new centre of balance in a spiritual world where God is, which is inside himself. He no longer lives in the moral world of the conflict of good and evil. The world he is in has only heaven and hell, a personal God who is human against a monster which is evil, that is, Satan.