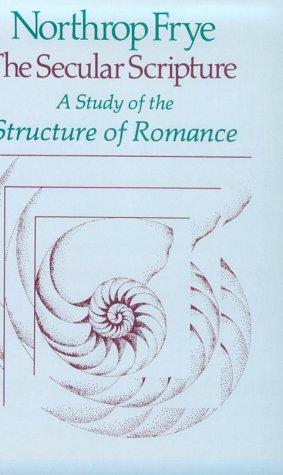

Eric Murphy Selinger of DePaul University is organizing a panel at the American Comparative Literature Association’s annual meeting to take place in Vancouver in the spring. The panel deals with romance in its widest sense. To his credit, I have never heard a lecture by Selinger in which he doesn’t cite Northrop Frye’s The Secular Scripture or Anatomy of Criticism. So, if you are working on romance, please consider submitting an abstract. Instructions for submitting an abstract are available at http://www.acla.org/acla2011/

Foreign Affairs: Romance at the Boundaries

• Seminar Organizer: Eric Murphy Selinger, DePaul U

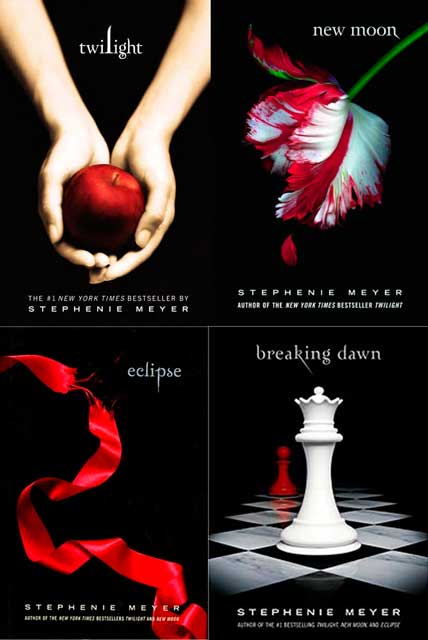

The 2011 ACLA conference theme invokes “the freshness, excitement, and, yes, fear of experiencing the ‘foreign.’” In the experience of love, that mix of emotions is also on display, not least when the “foreign” other turns out to be ourselves, “shattered” (in Jean-Luc Nancy’s terms) by the impact of desire. This seminar will explore how literary and popular texts represent the transformative encounter of self and other, mind and body, old self and new, in romantic love.

How do texts enact encounter aesthetically, through contrapuntal discourses, genres, allusions, or traditions? From Ottoman lyric to Harlequin novel, the literature of love is often highly conventionalized. How have such texts incorporated the freshness of the “foreign,” renewed within—or slipping past—the boundaries of genre?

What are the politics of xenophilia, within or outside of texts? What ethics (and erotics) shape our acknowledgement, violation, or fetishizing of alterity? How does power shift when texts and tropes of love move from language to language, medium to medium, period to period, audience to audience?

Is scholarship also a “foreign affair”? What pleasures and shames shape academic encounters with popular romance, the abjected Other of “literature”? What happens when men study (and write) texts commonly construed to be “by women, for women,” or when women study (and write) male romance? As queer readers study heteronormative texts, and straight readers, queer ones—when East meets West, and South, North—might love of the “foreign” be read as a critical practice, or criticism, a practice of love?