Several weeks back Michael Happy asked me if it would be possible to reconstruct a three‑dimensional diagram of Frye’s Great Doodle, the intricate and grand schematic of the alphabet of forms that figured so importantly in his design for his aborted “third book.” I replied that I didn’t think so because it would be too complex. What is the Great Doodle?

Frye writes at one point that he’s not revealing what the Great Doodle is because he does not really know (CW 23, 76–77), but his frequent references to it reveal that it is primarily his symbolic shorthand for the monomyth. Originally he conceived of the Great Doodle as “the cyclical quest of the hero” (CW 9, 214) or “the underlying form of all epics” (CW 9, 241). But as he began to move away from strictly literary terms toward both religious language and the language of Greek myth and philosophy, another pattern developed, one with an east-west axis of Nous-Nomos and a north-south axis of Logos-Thanatos. At this point the Great Doodle took on an added significance, becoming a symbolic shorthand for what he called the narrative form of the Logos vision: “the circular journey of the Logos from Father to Spirit” (CW 9, 260) or “the total cyclical journey of the incarnate Logos” (CW 9, 201). But the Great Doodle is never merely a cycle. Its shape requires also the vertical axis mundi and the horizontal axis separating the world of innocence and experience. These axes, with their numerous variations, produce the four quadrants that are omnipresent in Frye’s diagrammatic way of thinking. In Notebook 7 he refers to the quadrants as part of the Lesser Doodle (CW 23, 76), meaning only that the quadrants themselves are insufficient to establish the larger geometric design of the Great Doodle.

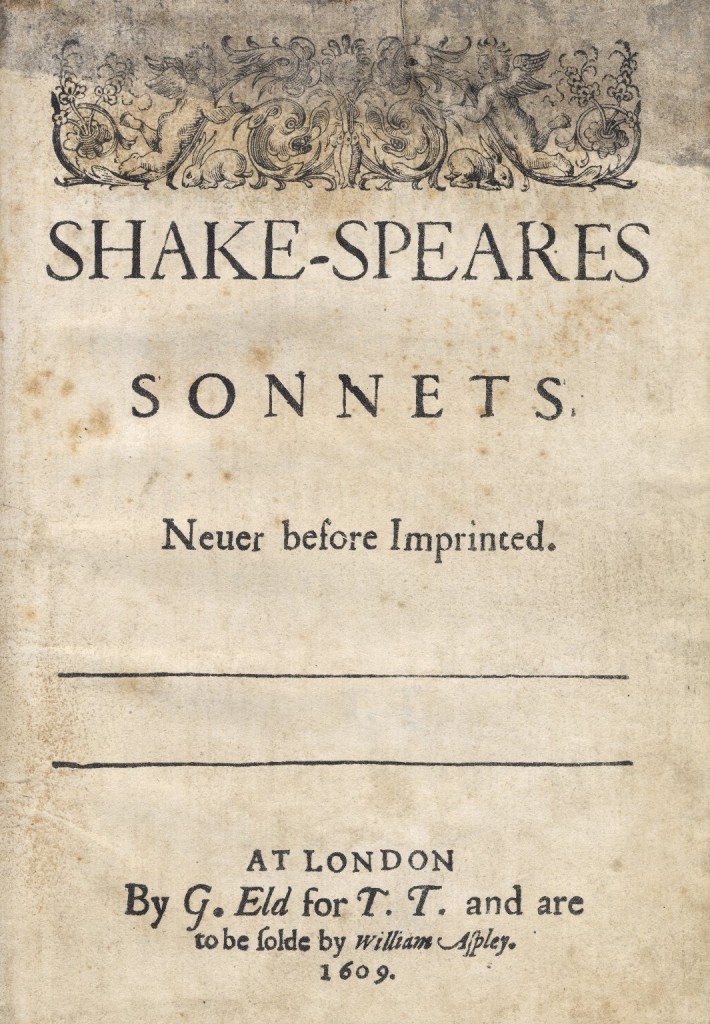

But the Great Doodle has still further elaborations. In the extensive notes he made for his Norton Lectures at Harvard (The Secular Scripture) Frye remarks self-referentially that in book 14 of Longfellow’s Hiawatha the heroine “invents picture-writing, including the Great Doodle of Frye’s celebrated masterpieces.” The reference is to Hiawatha’s painting on birch bark a series of symbolic and mystic images: the egg of the Great Spirit, the serpent of the Spirit of Evil, the circle of life and death, the straight line of the earth, and other ancestral totems in the great chain of being. Frye elaborates his Great Doodle in a similar way, the Hiawathan “shapes and figures” becoming for him points of epiphany at the circumference of the circle––what he twice refers to as beads on a string (CW 9, 241, 245). The beads are various topoi and loci along the circumferential string. They can be seen as stations where the questing hero stops in his journey or as the cardinal points of a circle. Frye even overlays one form of the Logos diagram with the eight trigrams of the I Ching, saying that they “can be connected with my Great Doodle” (CW 9, 209), and one version of the Great Doodle recapitulates what he refers to throughout his notebooks as “the Revelation diagram,” the intricately designed chart that he passed out in his course “Symbolism in the Bible.”

The Great Doodle, then, is a representation, though a hypothetical one, that contains the large schematic patterns in Frye’s memory theater: the cyclical quest with its quadrants, cardinal points, and epiphanic sites; and the vertical ascent and descent movements along the chain of being or the axis mundi. It contains as well all the lesser doodles that Frye creates to represent the diagrammatic structure of myth and metaphor and that he frames in the geometric language of gyre and vortex, center and circumference. (See Michael Dolzani’s exposition of the Great Doodle in his introduction to The “Third Book” Notebooks.)

Frye drew scores of diagrams in his notebooks but never one for the Great Doodle. And, as I say, it seems practically impossible to in include all the features of Great Doodle in a single diagram, even a two‑dimensional one. But Michael Happy’s question got me to thinking about Notebook 11f, which dates from 1969–70, where Frye toys with the idea of constructing a book of one hundred sections, which are clearly a part of the Great Doodle. Here are his initial musings about this scheme: