Parts of this post come from my introduction to Eva-Lynn Jagoe’s plenary lecture – The Linda Hutcheon and J. Edward Chamberlin Lecture in Literary Theory – at the annual conference at the Centre for Comparative Literature.

I recently had the great pleasure of studying and learning in an experimental setting. The goal of the course – Proust and Modernity – was to read Proust in relation to Modernity alongside various theoretical texts. The theory texts consisted of the usual suspects: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Fredric Jameson, Jacques Lacan, Kaja Silverman, Julia Kristeva, Malcolm Bowie, and Carol Mavor. The course itself consisted of response papers, presentations, and a term paper. Nothing, so far, out of the ordinary. Well, let me introduce the first oddity: only one of the students had read Proust previously, and the professor like the rest of the students was reading Proust for the first time. We ultimately, toward the end of the class, called this “virginal reading.”

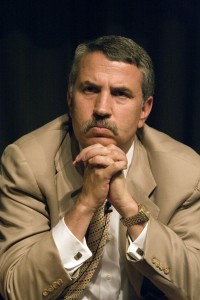

Most readers of this blog will likely have never encountered Eva-Lynn Jagoe, the author (currently at work on “the long novel”) or the professor, so let me briefly indulge here in giving some account of her as instructor. In the classroom, Professor Jagoe’s central goal is always to test ideas and question students and their ideas. Her classroom is a laboratory for readers. The first thing to know is that Eva-Lynn often seeks to break down the institutional walls of the structure: we ultimately tossed the syllabus. In its place, each student agreed to offer commentary, work through Proust, and decide with Professor Jagoe (I’m oscillating between the professorial and the personal precisely because blurring of lines is so important, and to show that students ultimately did recognise there was a professor in the room) how we would be evaluated – but evaluation, as a university requirement, takes on a new role in her classroom. Throughout the course on Proust, we experimented with a new pedagogy and a new classroom experience (or, perhaps, just new to me, but something felt novel). The classroom always has food, always has drinks, always had laughter: these were the requirements. Additionally, we were to read and discuss the novel from personal, subjective, and confessional starting points – which, naturally, makes Proust the near perfect subject of study. It is in this space that we, students and professor, began to experiment with modes of teaching, modes of learning, modes of reading.

Initially, we had set upon reading a series of theorists in addition to Proust and we had agreed to follow Roger Shattuck’s plan of study for reading Proust. However, as we began to read, we realised that something was not working; we were not able to do what we had wanted to do, which was read Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Thus, the critical readings became optional and then later they became obsolete. In addition to tossing the theory, we added an extra hour to our Friday sessions. One of our meetings lasted over five hours, we left around 6 pm on a Friday, we began at 1, and the discussion continued over email. In the classroom, Professor Jagoe managed to create something of a utopian space in which Proust was read, discussed, and in many ways dreamed into the living. In these moments, Proust became real, or we became Proustian and from here the text was no longer studied in and of itself, but in relation to the greater problem of the imagination. Proust, of course, will teach this very lesson in the last volume of the novel, he writes: “In reality, every reader is, while he is reading, the reader of his own self. The writer’s work is merely a kind of optical instrument which he offers to the reader to enable him to discern what, without his book, he would perhaps never have expressed himself. And the recognition by the reader in his own self of what the book says is a proof of its veracity.”

Continue reading →