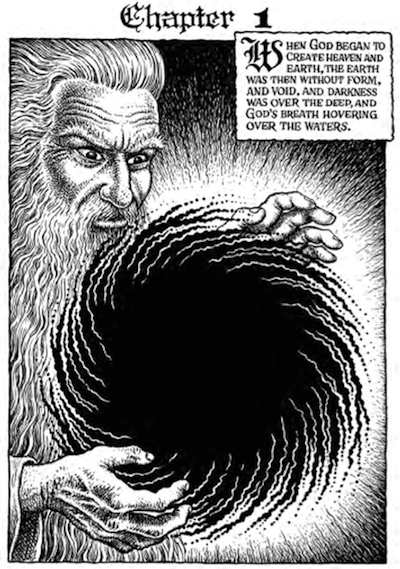

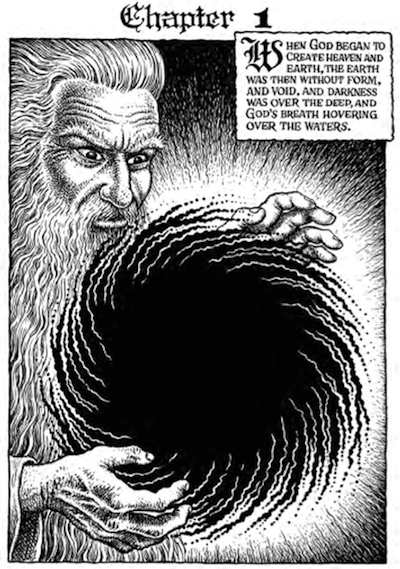

The opening panel of R. Crumb’s The Book of Genesis, translated by Robert Alter

Thanks to David Richter for the engaging discussion of the last couple of days. I hope I am not belaboring matters by “piling on,” but I wanted to address some points that I believe are worth clarifying.

Concerning Alter’s catching Frye in his mistranslation of the word that is translated as “vanity” in the King James Bible: Frye does not say the word means fog; he says that the word “has a metaphorical kernel of fog, mist, or vapour” (143) –Alter translates it as mist, vapour, breath – and that “[i]t thus acquires a derived sense of ‘emptiness,’ the root meaning of the Vulgate’s vanitas.” Frye also notes that the word is echoed in James in the New Testament. The passage in James is: “Whereas ye know not what shall be on the morrow. For what is your life? It is even a vapour, that appeareth for a little time, and then vanisheth away.” The difference between fog and mist is the density of the vapor, a fairly hazy matter. Frye does go on in his discussion of Ecclesiastes to speak of “dense fog,” but this is a page later and in a different context: “We see by means of light and air: if we could see air we could see nothing else, and would be living in the dense fog that is one of the root words of the word ‘vanity’” (144). So actually, it hardly qualifies as a mistranslation and it does seem like quibbling on Alter’s part. Alter hardly skewers him, except perhaps in his own mind; he is skewering a phantom, since he doesn’t bother providing a fair representation of what Frye says in the first place.

As for “overarching unity,” Alter makes the very same point as Frye about the Bible’s unity and coherence in his discussion of allusion in The World of Biblical Literature: he writes that for all the Bible’s “diversity, there is also a kind of elastic consensus that expresses itself in certain shared values and concepts, accompanied by a shared set of images, idioms, model figures, and exemplary stories. . . . certain notions of God, man, nature, and history that came to define national consciousness were locked into these habits of allusion. God’s sovereign power seen as a transformation of primal chaos into order and the liberation from Egyptian bondage seen as the great sign of Israel’s historical election were so central that writers of the most disparate aims and backgrounds repeatedly rang the changes on these ideas as they had been classically formulated in Genesis and Exodus, respectively. Allusion, then, becomes an index of the degree to which ancient Hebrew literature was on its way from corpus to canon, even if certain later institutional notions of canonization would have been alien to it. For the prominent play of allusion requires that the sundry texts be put together, taken together, seen, eve in in their sharp variety, as an overarching unity.”

Alter of course downplays this unity (he admits it but resists the dynamic imaginative logic of the allusiveness he is discussing), and that is fair enough, since it is not what Alter is particularly interested in as a realist or mimetic critic (and he is a very good one, there is no doubt). But he does see the Bible as having, even in its “sharp variety,” “an overarching unity.”

Also, why such a denigration of typology? The Hebrew Bible or Old Testament, as Frye points out, “is much more genuinely typological without the New Testament than with it. There are, in the first place, events in the Old Testament that are types of later events recorded also within the Old Testament. . . . For Judaism the chief antitypes of Old Testament prophecy are, as in Christianity, the coming of the Messiah and the restoration of Israel, though of course the contexts differ” (102). Where else did the Jews who wrote the Gospels get the idea in the first place? They got it from their own Bible. Biblical typology and narrative are the basis of the West’s dialectical and revolutionary sense of history, and it didn’t come from Christian myth alone, but originally from Judaic myth. The Christian Bible and the way it presents itself to be read is not illegitimate simply because it includes as part of its canon the Hebrew scriptures and reads them in a different way and according to a different typology from that of the Hebrew Bible.

Nor is Frye a biblical scholar who can be readily accused of reading the Bible through Christian doctrine. As he points out, quite to the contrary his own Methodist roots gave him a strong sense of the Bible as story, as narrative, not as doctrine. His primary reading of the Bible is a reading of the King James Bible, precisely because he is interested in the Bible in its own right as an imaginative and “kerygmatic” structure, but also as a mythological and prophetic language of imagery and story that has deeply informed Western literature. Why should such an approach be scorned or dismissed out of hand, when it can give us deeper understanding of that culture and its literature?

I can certainly understand why one might want to call a critic like Bloom to task (and Alter does a very good job of it in The World of Biblical Literature), given the erratic and idiosyncratic nature of his criticism. But why make Frye, a critic and thinker of genuine genius and consistent and systematic interpretive principles and practice, the subject of the same ill treatment? Why is his form of criticism – which is in fact the farthest thing from free association – not as legitimate as the other biblical critics and theorists mentioned in your course outline, all of whose approaches are bound to be limited in one way or another? Some of the other critics you mention – but certainly not all – may have better Hebrew but, compared to Frye, their grasp of narrative structures and metaphorical imagery is rudimentary at best.