Further to Clayton’s and my own last post, there is another great passage from Thoreau, another powerful attack on moral and political compromise, from “Slavery in Massachusetts.”

This one, with its turning to the beauty of Nature in contrast with the ugliness of human-all-too-human-compromise, brings to mind one of the paragraphs Bob quoted in his post on Frye and The Funny: “A sense of humor, like a sense of beauty, is a part of reality, and belongs to the cosmetic cosmos: its context is neither subjective nor objective, because it’s communicable” (Late Notebooks, 1:227).

At the end of the Garden chapter in Words with Power, Frye writes: “The progress of criticism has a good deal to do with recognizing beauty in a greater and greater variety of phenomena and situations and works of art. The ugly, in proportion, tends to become whatever violates primary concern” (226-27).

Hence Thoreau’s recourse in the passage below to the aesthetics and beauty of nature, in contrast with which the violation of primary concern that is the morally disgusting reality of slavery appears all the more ugly and loathsome. Thoreau is always polarizing and separating. His images and rhetoric, to use Clayton’s words, ” cut through all the cowardly, sissified, hand-wringing bullshit” and drive home what Frye calls the “black-and-white situation.”

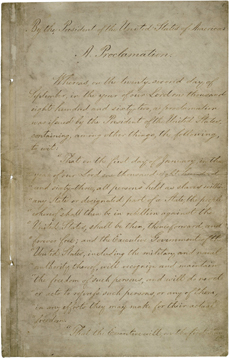

Thoreau, being a true prophet, wasn’t in the habit of mincing his words, and he was seriously pissed when he wrote these ones, in response to the controversial arrest and “rendition” by the state of Massachusetts of a fugitive, Anthony Burns, to his oppressor in the South, which brought the army to Boston to shut down the abolitionists who had stormed the federal courthouse to free him.

His moral disgust in this case is primarily expressed through the nose: the odor of one’s actions, not the profession of belief, are what matters. It is the odor of one’s deeds that advertises one’s moral quality, and so let your deeds smell consistently sweet so as not to clash with the fragrance of the water-lily, which, like Nature, has made no compromise, Missouri or any other kind.

The reference to a “Nymphoea Douglasii” is an allusion to Stephen Douglas, the architect of the Fugitive Slave Act, who was later defeated by Lincoln in the presidential election. (If there is an analogy here to the Anglican Church’s attitude to homosexuality, Rowan Williams is perhaps more of a Lincoln than a Douglas, in his temporizing strategy, if that is what his strategy is.)

Here is the passage from Thoreau, the closing passage of the speech:

I walk toward one of our ponds; but what signifies the beauty of nature when men are base? We walk to lakes to see our serenity reflected in them; when we are not serene, we go not to them. Who can be serene in a country where both the rulers and the ruled are without principle? The remembrance of my country spoils my walk. My thoughts are murder to the State, and involuntarily go plotting against her.

But it chanced the other day that I scented a white water-lily, and a season I had waited for had arrived. It is the emblem of purity. It bursts up so pure and fair to the eye, and so sweet to the scent, as if to show us what purity and sweetness reside in, and can be extracted from, the slime and muck of earth. I think I have plucked the first one that has opened for a mile. What confirmation of our hopes is in the fragrance of this flower! I shall not so soon despair of the world for it, notwithstanding slavery, and the cowardice and want of principle of Northern men. It suggests what kind of laws have prevailed longest and widest, and still prevail, and that the time may come when man’s deeds will smell as sweet. Such is the odor which the plant emits. If Nature can compound this fragrance still annually, I shall believe her still young and full of vigor, her integrity and genius unimpaired, and that there is virtue even in man, too, who is fitted to perceive and love it. It reminds me that Nature has been partner to no Missouri Compromise. I scent no compromise in the fragrance of the water-lily. It is not a Nymphoea Douglasii. In it, the sweet, and pure, and innocent are wholly sundered from the obscene and baleful. I do not scent in this the time-serving irresolution of a Massachusetts Governor, nor of a Boston Mayor. So behave that the odor of your actions may enhance the general sweetness of the atmosphere, that when we behold or scent a flower, we may not be reminded how inconsistent your deeds are with it; for all odor is but one form of advertisement of a moral quality, and if fair actions had not been performed, the lily would not smell sweet. The foul slime stands for the sloth and vice of man, the decay of humanity; the fragrant flower that springs from it, for the purity and courage which are immortal.

And here are the great closing words, where what is finally polarized and separated are life and death, the sweet scent of life and the rot of decay and death:

Slavery and servility have produced no sweet-scented flower annually, to charm the senses of men, for they have no real life: they are merely a decaying and a death, offensive to all healthy nostrils. We do not complain that they live, but that they do not get buried. Let the living bury them: even they are good for manure.

Thoreau is an excellent example of a writer whose writings go well beyond literature and the purely imaginative and are very much in the meta-literary dimension of the kerygrmatic, of spiritual proclamation.