On the face of it, one wouldn’t think that Frye would take a very sympathetic view of Calvin, but here’s a piece he wrote on Calvin at an age when most of us were trying to stagger through an undergraduate curriculum. He was two years past his majority. Perhaps his conclusion about the interpenetration of the historical and transhistorical is relevant to the discussion of both/and.

“The Importance of Calvin for Philosophy”

by Northrop Frye

To make one’s mark in the contemporary world of scholarship one must be both erudite and eclectic: the present age has a vast number of intellectual interests, and the attainments of those who specialize in any one of them are looked upon with respect increasing in proportion as the field becomes more narrow and intense. The high priests of modern learning are expected to be able to talk unintelligibly about their particular subjects and to require a hair splitting nicety of statement from their acolytes. As a result, laymen feel a certain hesitancy in handling the really important questions of those cultural disciplines with which they are unfamiliar and prefer to have the assurance of expert opinion before canonizing any prejudice which involves them.

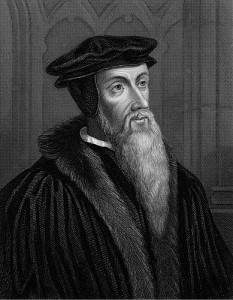

Why theology should be so grotesque an exception to this rule it is by no means easy to say. Perhaps the safest working assumption is that people are anxious not to concede the validity of theology’s claim to be a cultural discipline because, once theology is recognized, religion must be recognized too, and if religion be recognized, what would become of contemporary society? So the well educated, enlightened man of today grows up with a superstitious awe of science, and a certain amount of respect for philosophy and the arts, but is quite prepared to group theology with alchemy or kabbalism and to talk of religious developments in terms which, by the standards set for any other intellectual pursuit, would disgrace a six year old. Probably most of us will spend a good deal of time explaining gently to otherwise well informed people that mysticism is not the same thing as mistiness, that predestination is not fatalism, or that the ordinary priggish rule of thumb bourgeois morality of the nineteenth century, according to which, if one observed the fifth and seventh commandments, one could break the other eight with impunity, is not Puritanism. After doing that, we should not be too much shocked if we find that John Calvin, who has done more to influence our conception of God than any other man, should be for many people an incarnation of the devil. For the stock caricature of Calvin as a merciless and humourless sadist who really believed only in hell would make a very fair Satan for some aspiring Milton. There may be a few even in so initiated a group as this whom it might be expedient to remind that Calvin was not a Scotchman, that he was only indirectly responsible for Calvinism, and that he was not responsible at all for degradations and perversions of his teachings made by superstitious bigots.

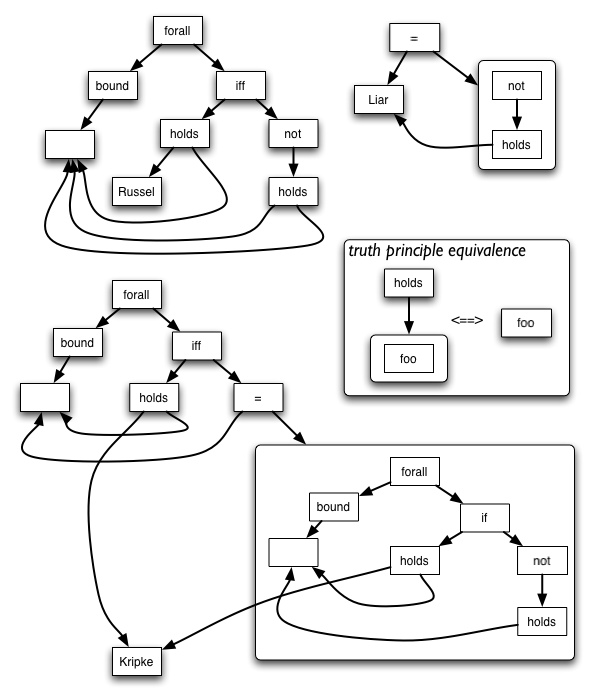

We are not concerned tonight with the rehabilitation of Calvin’s character, but with the investigation of a problem closely bound up with the contemporary abhorrence of him, which may prove, on analysis, to be less inexplicable than it is ignorant and ill considered. The problem may be briefly stated thus. There is no clear line between theology and philosophy: the questions they respectively deal with cannot be disentangled. Both are rationalized accounts of the interrelation of soul, external world, and God. Both rest on axioms supplied by faith. The difference between them is a difference of emphasis. At some periods the theologian and the philosopher become merged into one thinker: thus, Aquinas was the greatest philosopher of his time because he was its greatest theologian, and vice versa. Schleiermacher in modern times provides a parallel synthesis. In Calvin we have a theologian with a first class brain; posterity may prove him wrong, but it cannot prove him a fool: why, then, does he not at least touch on the problems of philosophy? A general history of philosophy is bound to mention Aquinas; it finds no occasion to mention Calvin. The questions which are implied in this include two of some importance: First, does Calvin’s theology have any integral connection with the philosophical thought of Calvin’s time, as is the case with Aquinas? Second, has Protestantism such a thing as a philosophical foundation at all? The former is the subject of our immediate enquiry.