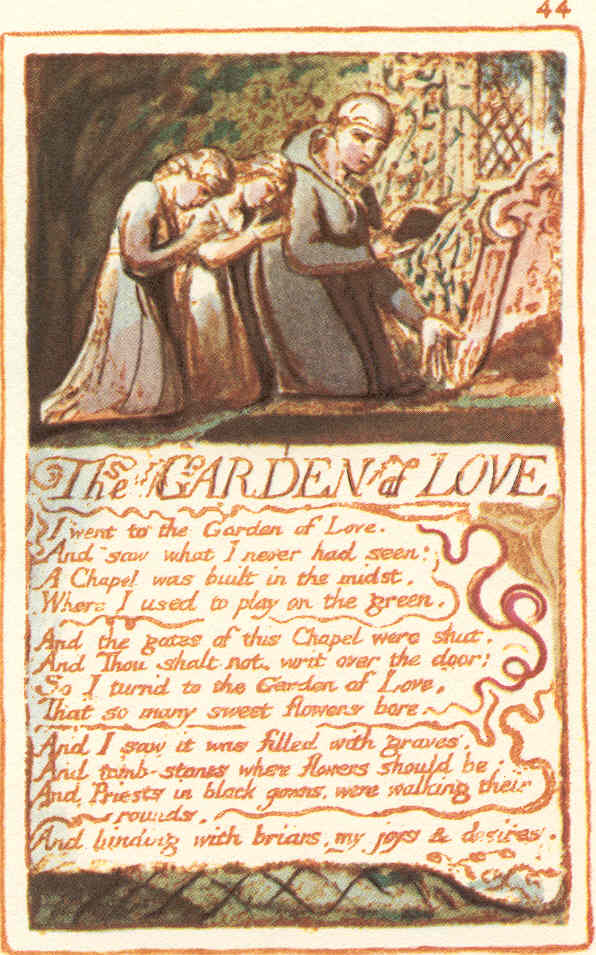

“Those who restrain desire do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained, and the restrainer or reason usurps its place and governs the unwilling. And being restrained, it by degrees becomes passive, till it is only the shadow of desire. . . . Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires.” “Enough, or too much”—but never less than enough.

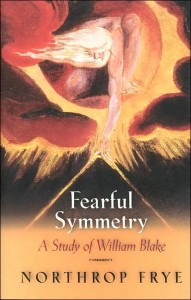

That’s Blake. That’s Frye.

Yes, Frye did refer to human beings as psychotic apes, contemplating the record of misery and horror that history displays. “Desire” in Frye, as in Blake, is of course not the same as the compulsion to hurt and control others—“to govern the unwilling”—which is a mental illness, not desire at all. Frye was not like Freud, especially on the issue of desire. It is ironic, Frye says, that Freud has become a prophet of eros—ironic, because Freud was deeply pessimistic about human nature; he wanted, Moses-like, to hand down the law from his height of authority. Frye was not a pessimist of this type, at all.

That’s another thing that makes him so different. Consistent with his profound valuation of desire, Frye was deeply committed to what goes with it, namely, an insistence on the value and meaning of life, confidence in the meaningfulness of existence, in fact in the divinity of life. There is something divine in human nature—that’s Frye. Indeed this divine aspect is manifested in our desires, in our wishes and their converse, our fears, and what we do about our fears and desires. Such a conviction is utterly at odds with poststructuralism, particularly in deconstruction, which floated on a sea of shallow, leisure-class pessimism.

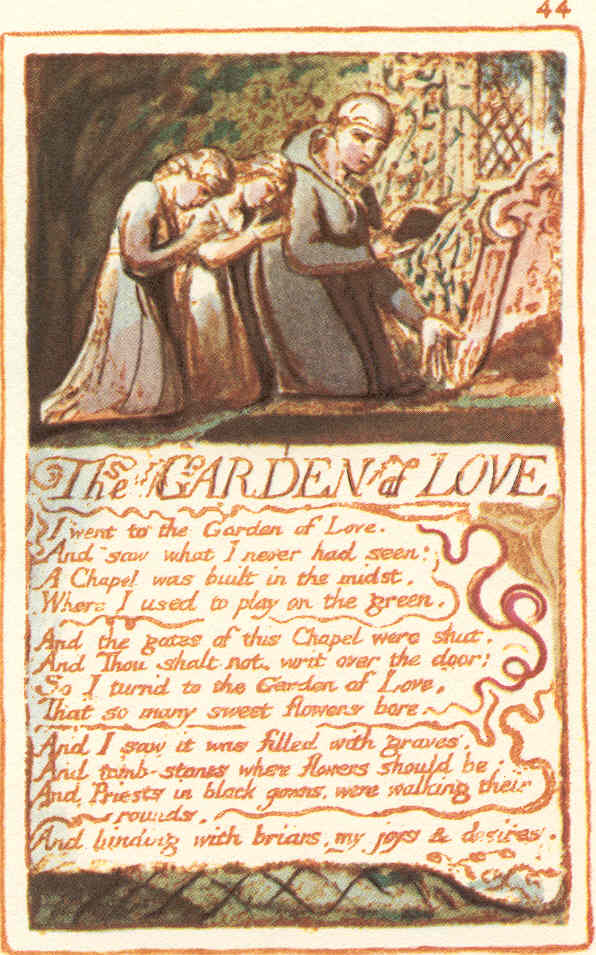

But then, on the topic of desire, Frye is unlike most of intellectual culture. Desire is almost universally devalued—in religion (Christianity-Judaism-Islam is full of it), in philosophy, in psychology (certainly in the psychoanalytic tradition, which so many academics find irresistibly appealing), in economics—you name it. Curiously, the one area that consistently respects desire is literature—Frye’s area. By contrast, the prevailing attitude is that human desire is a problem, often THE problem. “Good” is reflexively understood to mean “obedience.” (“Were you good today?” Mommy asks, meaning “Did you do what you were told—did you obey?”) If people could only stick to obeying authority—doing what they are told to do, wanting what they are told to want, and no more—they would be OK. Instead, they foolishly listen to desire. Ignorant desire then gets them into all kinds of problems and causes problems for those who obey. This is of course Freud’s program: superego, with its “Don’t” command, must replace “libido.” “Thou shalt not,” as Blake puts it in “The Garden of Love.” Even in economics, supposedly about people doing what they want, scarcity is the ruling principle. There is not enough. Some people will have to do without.

In fact, this is a key reason why desire is so much distrusted: desire incites disobedience, chaos, disorder. Most of history shows us a tiny minority of the population in control of the rest of the population, who work for a living (as opposed to owning for a living). Unless those who do the work have their desires carefully pruned to fit the dominant arrangement, there is going to be trouble. There are a lot of reasons why desire is so distrusted, and it is not an accident that Blake is considered and considered himself a radical.

Frye was not a radical quite in Blake’s style, but there are plenty of radical currents in his thinking. You don’t have to read far in his notebooks—or his publications—to find him saying radical things, things that have annoyed a lot of people. One of the most important things he says is to insist on the value of human desire.

This partly explains, by the way, why he is so despised in the academy today.