Here is Clayton Chrusch’s excellent summary of Chapter Three of Fearful Symmetry. Beyond Good and Evil:

But as only the worst of men would torture other men in hell endlessly, given the power, those who believe God does this worship the devil, or the worst elements in man.

1. Evil is turning away from the imagination and restraining action.

I’ll let Frye introduce this chapter:

We now come to Blake’s ethical and political ideas, which, like his religion, are founded on his theory of knowledge. It is impossible for a human being to live completely in the world of sense. Somehow or other the floating linear series of impressions must be ordered and united by the mind. One must adopt either the way of imagination or the way of memory; no compromise or neutrality is possible. He who is not for the imagination is against it.

This whole introductory section is worth reading in the original. In short, evil is turning away from perception rather than passing through it to vision. Evil is an attempt to restrain the imagination, to restrain life, and so it is ultimately a death impulse. Restraint is what characterizes all evil–restraining oneself or restraining another. Evil is not active except where the purpose is to frustrate further activity. And so all vices are negative things–negations of action, negations of one’s senses, negations of imagination. It follows, as Blake writes, “all Act is Virtue.”

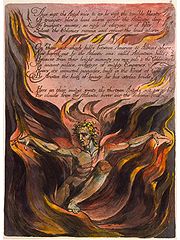

The negation of the imagination can also be thought of as a perversion of it. A perverted imagination descends quickly into either fear or cruelty. Cruelty is mischievous curiosity, and fear “is not so much the horror of the unknown as a fascinated attraction to it.” In society, the cruel become tyrants and the fearful become victims. Imaginative people are rare enough that history in retrospect looks very much like an unchanging parasitic relationship between tyrant and victim, a relationship supported as much by the cowardice of the victim as the cruelty of the tyrant.

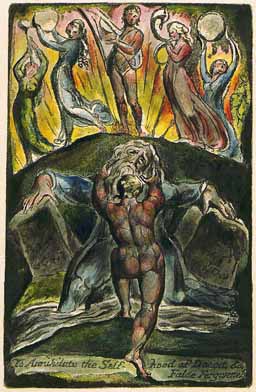

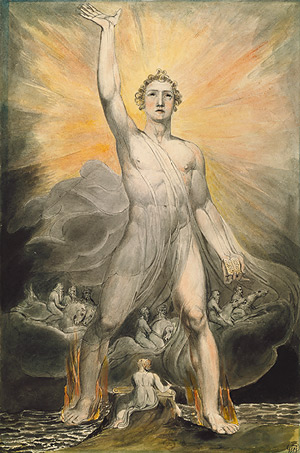

The imagination is self-development, which “leads us into a higher state of integration with a larger imaginative unit which is ultimately God.” What is egocentric in us is incapable of the expansion outward that characterizes self-development. And so Blake accepts a view of original sin in which there are two parts to us, a part capable of only good, and a part capable of evil as well as good. So Frye writes, “Man has within him the principle of life and the principle of death: one is the imagination, the other the natural man.”

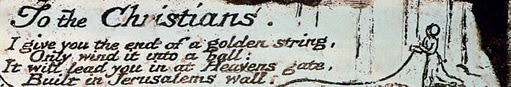

The cure for original sin is vision, a recognition that the world we live in is fallen but not final–that a better world and a better humanity are possible. Good, honest people who lack this vision are on the right side, but still have not achieved all they can. A person with vision is a prophet. Prophecy is not a mysterious ability of telling the future, it is simply the imaginative activity of “an honest man with a sharper perception and a clearer perspective than other honest men possess.” This perception reveals an “infinite and eternal reality.”

2. State religion is that of the self-righteous prig who is the Prince of this world.

The source of all tyranny is not in the temporal world, but in the sense of “a mysterious power lurking behind” powerful people. Generating this sense of mystery is the work of state religion and the caste of priests who administer it. So as pernicious as tyrants are, we cannot end tyranny by overthrowing tyrants. Tyranny is founded on false religion and the only cure for it is true religion.

You can tell false religion because it posits a God “who is unknown and mysterious because he is not inside us but somewhere else: where, only God knows. Second, it preaches submission, acceptance and unquestioning obedience.” False religion is state religion and exists to rationalize power, but it is constantly under attack by the imagination. The imagination causes false religion to constantly alter and solidify its form and eventually can succeed in forcing false religion into a consolidation of error, which is a perfect negation of truth. This consolidation of error makes false religion much more vulnerable than would the vagueness and fog which are its preferred anti-imaginative weapons.

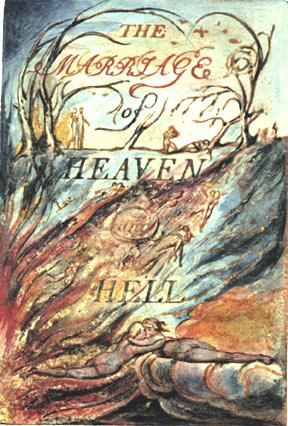

False religion achieves its highest form in the God of official Christianity who was invented to counter the genuine teachings of Jesus. Frye writes,

This God is good and we are evil; yet, though he created us, he is somehow or other not responsible for our being evil, though he would consider it blasphemous either to assert that he is or to deny his omnipotence. All calamities and miseries are his will, and to that will we must be absolutely resigned even in thought and desire. The powers that be are ordained of him, and all might is divine right. The visions of artists and prophets are of little importance to him: he did not ordain those, but an invariable ritual and a set of immovable dogmas, which are more in keeping with the ideas of order. Both of these are deep mysteries, to be entrusted to a specially initiated class of servants. He keeps a grim watch over everything men do, and will finally put most of them in hell to scream eternally in torment, eternally meaning, of course, endlessly in time. A few, however, who have done as they have been told, that is, have done nothing creative, will be granted an immortality of the “pie in the sky when you die” variety.

Frye then qualifies this by saying, “It is easy to call this popular misunderstanding, but perhaps harder to deny that orthodox religion is founded on a compromise with it.” Worshipping a God who, among other things, tortures men forever, means worshipping the devil. This devil does not exist except as bogeyman projected by priests and rulers, and yet somehow this does not prevent him from being the “Prince of this world.”

As the Prince of this world, the devil demands obediance, uniformity, and mediocrity, all of which are called good in official morality. Thus, “all that is independent, free and energetic comes to be associated with evil.” Satan, who is the accuser of sin, is “not himself a sinner but a self-righteous prig.”

For Blake, engaging in good vs. evil battles, whatever one’s conception of good and evil, is an expression of a death impulse. Life requires a battle, but it is a battle between truth and error.

Satanism, in Blake’s time, was most perfectly expressed as Deism, characterized by a belief in the physical world as the only real one and an almost enthusiastic resignation to the conditions and restrictions the physical world imposes on human life. Though contentment seems like a reasonable approach to life, it fails spectacularly in practice, leading to hysteria and warfare. Furthermore, the imagination can never accept the fallen world that it finds itself in.

Continue reading →