Our summer project is to convert the material in both the Robert D. Denham Library and the Journal to PDF. The reason is simple: the text is easier to read, the pages are numbered, and — this is the best part — it is searchable. It means our scholarly material will have the scholarly cast it deserves. Our daily blog, meanwhile, will remain in its present format. It will take a little while to make this conversion, but it will happen soon.

Thomas Hardy and God

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sigcSoe45oE

A beautiful clip from the 1996 film adaptation of Jude the Obscure

More synchronicity: today is Thomas Hardy‘s birthday (1840-1928), and he adds nicely to our ongoing consideration of religion, compassion for the poor, and the pseudo-literal conception of God. Here’s Frye in “The Times of the Signs”:

A later poet, Thomas Hardy, is never tired of showing what an imbecile God turns out to be if we create him in the image of the starry order. Hardy has a poem called God’s Education, in which God is represented as learning from the misery of man, in the manner of middle-class people reluctantly coming to realize that some people are not only poor but poorer than they should be. He has another called By the Earth’s Corpse, where God remarks, at the end of time, that he wishes he had never started on this creation business, for which he clearly has so little talent. (CW 27, 349)

Video of the Day: Harold Bloom Interviewed by the New York Times

Reinhold Niebuhr: America and the Promised Land

Reinhold Niebuhr died on this date in 1971 (born 1892). From a circa 1952 CBC radio review of Niebuhr’s The Irony of American History:

American history is ironic, according to Dr. Niebuhr, because it has not turned out the way that the great Americans of the Revolutionary period expected. To Jefferson, for instance, America was the new Promised Land: it was making a new beginning in history, and was avoiding the mistakes of the past by getting rid of kings and nobles. As far as possible America turned her back on the rest of the world and tried to work out her own destiny. She got very rich and prosperous, and this seemed like a reward for her merits. But now Americans have suddenly found themselves, not out of the world, but practically holding it up, like Atlas. They also find that their prosperity, which has given them this position, is the very thing that makes it hardest for them to hold their allies. Now if America strikes an attitude of outraged virtue, she will succeed in isolating herself, and if she does that she’s done for. She has to realize that, with all her good will, a lot of the ideas she has cherished about her destiny are sentimental illusions, not very different from the illusions the Communists use as bait for mass support. The best American attitude for today is the one represented by Lincoln during the Civil War. Lincoln was sure of the justice of his cause, and he was convinced that the United States, like the world today, couldn’t survive half slave and half free. But still he warned against self-righteousness, against assuming that those who were fighting the Union were sub-human, and so he adopted the Christian principle of malice toward none, and charity toward all. (CW 10, 321-2)

Unspeakable Atrocities in Damascus

Here. Terrifying, soul-rending.

Rameses the Great and “Literal” Meaning in the Bible

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h0MrvvW_kiY

“New evidence linking Rameses and Moses”

A little synchronicity: Rameses II the Great became pharaoh of Egypt on this date in 1279 BCE; Frye makes reference to him in “Symbolism in the Bible” to correct misapprehension about the “literal” meaning of the Bible. The Bible records not history, but a typological manifestation of concern:

[W]hen John the Baptist is asked if he is Elijah, he says that he is not. Now, there is no difficulty there, unless you want to foul yourselves up over a totally impossible conception of literal meaning: reincarnation in its literal there’s-that-man-again form is not a functional doctrine in the Bible. At the same time, metaphorically, which is one of the meanings of “spiritually” in the New Testament, John the Baptist is a reborn Elijah just as Nero is a reborn Nebuchadnezzar or Rameses II. So, it is not surprising that the great scene of the Transfiguration in the Gospels should show Jesus as flanked by Moses on one side and Elijah on the other — that is, the Word of God with the law and the prophets supporting him. Again, that has its demonic parody in the figure of the crucified Christ with the two theives flanking him on either side. (CW 13, 499-50)

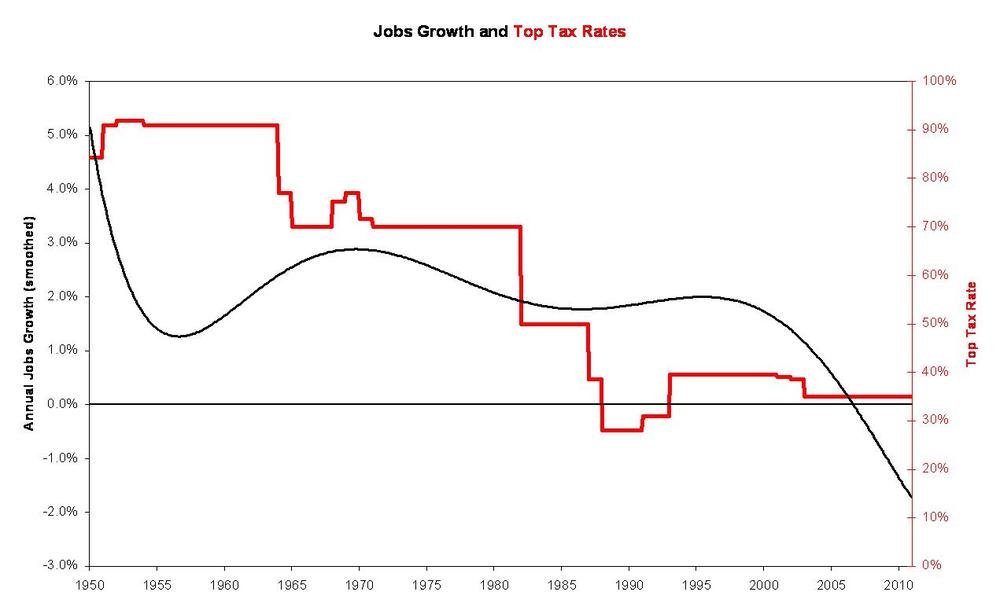

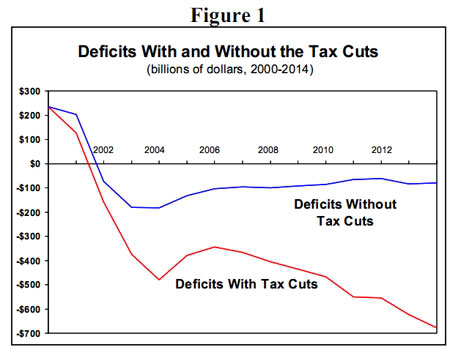

Taxes, Jobs, Deficits

Diminishing return: lower taxes result in lower job growth in the long run — note the nosedive after the Bush tax cuts in 2000.

Uh oh: the larger the high-end tax cuts, the larger the deficit — note the explosive growth of the deficit after the Bush tax cuts of 2000 (red line). Note also that if the Bush tax cuts were repealed, the deficit drifts easily into manageable territory (blue line).

If we’re talking bottom line, here it is: lower taxes have demonstrably meant diminishing job creation (not to mention devastated social services) and larger deficits. We know that’s not been the conventional wisdom since the storied days of Ronald Reagan in the misty past of thirty years ago, but it is the reality.

Even after eight years of Bushonomics that have crippled American fiscal policy, the current government of Canada is about to more or less repeat the same mistakes. Social and government services will be cut in the name of “austerity.” Welfare, meanwhile, is now strictly for corporations in the form of still more tax cuts, the purchase of tens of billions worth of American jet interceptors, and a massive payday for developers with the building of new prisons at a time when crime rates are down sharply after declining for a decade.

Frye on False Literalism: “The Bible is explicitly antireferential in structure”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cihcMqBgmPs

Picking up again on our examination of the relation of Christian fundamentalism to right wing politics, here’s Frye in “The Double Mirror” on the false literalism of fundamentalists. (It’s a long excerpt, but it leads up to the last paragraph that makes it worth the effort.)

The traditional view of the Bible, as we all know, has been that it must be regarded as “literally” true. This view of “literal” meaning assumes that the Bible is a transparent medium of words conveying a “true” picture of historical events and conceptual doctrines. It is a vehicle of “revelation,” and revelation means that something objective, behind the words, is being conveyed directly to the reader. It is also an “inspired” book, and inspiration means that its authors were, so to speak, holy tape-recorders, writing at the dictation of an external spiritual power.

This view is based on an assumption about verbal truth that needs examining. One direction is centripetal, where we establish a context out of the words read; the other is centrifugal, where we try to remember what the words mean in the world outside. Sometimes the external meanings take on a structure descriptive or nonliterary. Here the question of “truth” arises: the structure is “true” if it is a satisfactory counterpart to the external structure to it is parallel. If there is no external counterpart, the structure is said to be literary or imaginative, existing for its own sake, and hence often considered a form of permissible lying. If the Bible is “true,” tradition says, it must be a nonliterary counterpart of something outside it. It is, as Derrida would say, an absence invoking a presence, the “word of God” as a book pointing to “the word of God” as speaking presence in history. It is curious that although this view of Biblical meaning was intended to exalt the Bible as a uniquely sacrosanct book, it in fact turned it into a servomechanism, its words conveying truths or events that by definition were more important than the words were. The written Bible, this view is really saying, is a concession to time: as Socrates says of writing in the Phaedrus, it is intended only to call to mind something that has passed away from presence. The real basis of the Bible, for all theologians down to Karl Barth at least, is the presence represented by the phrase “God speaks.”

We have next to try to understand how this view arose. In a primitive society (whatever we mean by primitive), there is a largely undifferentiated body of verbal material, held together by the sense of its importance to that society. This material tells the society what the society needs to know about its history, religion, class structure, and law. As society becomes more complex, these elements become more distinct and autonomous. Legend and saga develop into history; stories, sacred or secular, develop into literature; a mixture of practical knowledge and magic develops into science. Society struggles to contain these elements within its overriding concerns, and tries to impose on them a structure of authority that will keep them unified, as Christianity did in medieval times. About two generations ago there was a fashion for crying up the Middle Ages as a golden age in which all aspects of culture were unified by common sentiments and beliefs. Similar developments, with a similar appeal, are taking place today in Marxist countries.

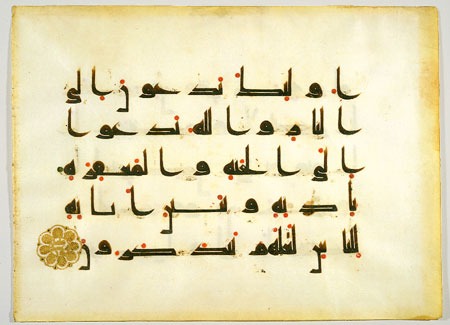

New to the Library: Frye on Islam and the Koran, Pt 2

Frye at the Movies: “Detective Story”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O8NnjbzsTP8

Frye refers to this movie in his 1952 diary as a “sardonic masterpiece.” Detective stories generally were a source of almost guiltless pleasure for him (even putting aside their value in studying popular and primitive archetypes), and he made reference to them often. However, this personal account in his 1942 diary of reading them is easily the most charming:

I don’t think that I have either a highbrow or a lowbrow pose about detective stories, but I don’t really quite understand why I like reading them. I read them partly for the sake of the overtones. I’m not a connoisseur of them: I can never guess what the hell’s up when the detective pulls out a watch and shouts: “My God, we may yet be in time!”, shoves the narrator and half the country’s police force into a taxi, dashes madly across town and finds the girl I’d placidly thought was the heroine all equipped with a blunt instrument & an animal snarl. I’m always led by the nose up the garden path in search of a false clue, and I never notice inconsistencies. And I always get let down when I find out who dun it. As I say, I like overtones. A good style, some traces of wit & characterization, a sense of atmosphere, and a lot of the professional intricacies of the game can go to hell. Yet I want a good novel in that particular convention & no other. The answer is, I think, that I’m naturally a slow & reflective reader, & make copious marginalia. In the detective story I live for a moment in the pure present: I’m passively pulled along from stimulus to stimulus, and, ignorant & idle as that doubtless is, I’m fascinated by it. Yet I seldom finish without disappointment. (CW 8, 15)