For the article that Michael Happy surely intends to write about Frye’s love affair with The New Yorker, here are the references—at least most of them—plus a few from Helen.

I have been rather handicapped by the lack of money, but that doesn’t matter so much this first term. But if you really want to do something for me, my own self‑sacrificing little girl—WHEN THE HELL ARE YOU GOING TO COME THROUGH WITH SOME NEW YORKERS? (Frye‑Kemp Correspondence, CW, 2, 620-1)

To switch the subject to civilization for the moment. Thank you very very much for the New Yorkers. You are a sweet little girl. It was just pure nerves that made me bark for them in my last letter [above]. The idea that you might have forgotten to buy them owing to pressure of work or something nearly made me collapse. I spent a marvellous weekend with them. It was just as well they came when they did, as the boots took my shoes Saturday morning to repair them and didn’t return them till Sunday morning—I had to go to Hall in my tennis shoes. (ibid., 630)

The poet may change his mind or mood; he may have intended one thing and done another, and then rationalized what he did. (A cartoon in a New Yorker of some years back hit off this last problem beautifully: it depicted a sculptor gazing at a statue he had just made and remarking to a friend: “Yes, the head is too large. When I put it in exhibition I shall call it ‘The Woman with the Large Head.’”) (Anatomy of Criticism, 87)

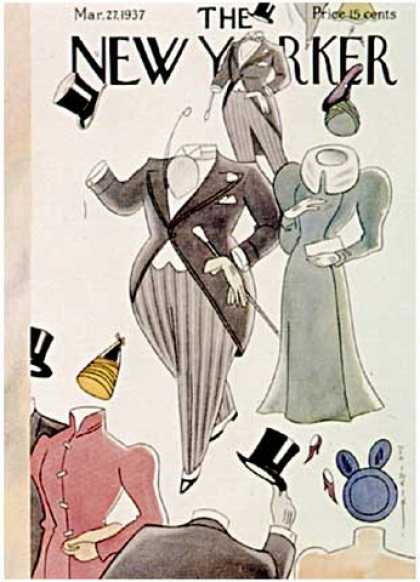

The dandy attitude survives in the early (twenties) essays of Aldous Huxley, whose epigrams are mainly inverted clichés, in Yeats’ association of dandyism & heroism, in Lytton Strachey, & in the contemporary New Yorker—see its Knickerbocker figure and again the inverted melodrama clichés of its cartoons. (Notebooks for Anatomy of Criticism, CW 23, 265)

Many years ago Edmund Wilson, in a New Yorker review, connected the Houdini situation with the dying & reviving god. [“And the magician who escapes from the box: what is he but Adonis and Attis and all the rest of the corn gods that are buried and rise? This is quite plain in the case of Houdini” (Classics and Commercials: A Literary Chronicle of the Forties (New York: Farrar, Straus, 1950), 151. Wilson’s review appeared in New Yorker, 11 March 1944.] (ibid., 294)

As I see it now, there are two main themes: the relation of literature to the other arts & disciplines, and the relation of the hypothetical to the existential: i.e., art & religion. I call it Tentative Conclusion, & begin, possibly, with the New Yorker cartoon. [The “head is too large” cartoon, referred to above]. (ibid., 202)

Don’t assume that the intentional fallacy is always a fallacy, i.e. that you can judge a satire without taking account of a humorous or ironic intention. The answer “but it’s supposed to be that way” is valid for many objections—cf. the New Yorker “large head” problem. [The “head is too large” cartoon, referred to above]. (ibid., 237)

Every Canadian has some feeling of sparseness when he compares, for example, Canada’s fifth largest city, which I believe is Hamilton, with the fifth largest across the line, which I believe is Los Angeles. And the same is true of poetry. Every issue of the New Yorker or New Republic, to say nothing of the magazines which really go in for poetry, contains at least one poem which is technically on a level with five‑sixths of Mr. Smith’s book [The Book of Canadian Poetry]. (Northrop Frye on Canada, CW 12, 29)

The political, and still more the economic, picture is one of deep gloom, lightened by an occasional gleam of neurosis. Like the map of Canada that you have been contemplating in Convocation Hall, it is a recognizable but oversimplified picture of a country coming apart at the seams. It reminds me of a New Yorker cartoon of two explorers caught in quicksand, one, who is already up to his neck, saying to the other: “Say what you will, I’ve half a mind to struggle.” The cultural situation, on the other hand, is a very exhilarating one. (ibid., 534)

Western historical dialectic gives me a pain anyway. God thought of us. He started us back in Nile slime & Euphrates mud, then the Greeks added reason, the Hebrews God, the Romans law and the British fair play, until here we are. Asia is irrelevant: it has no real history because it didn’t contribute anything to our great Western omelette. Phooey. In Sept. 1939 the New Yorker wrote a stentorous leader about a world of peace being plunged into war [“Notes and Comments,” in “The Talk of the Town,” New Yorker, 15 (9 September 1939): 9-10]. Two hundred million people, if that, go to war in Western Europe and that’s a world at war. Half a billion people have been fighting for years in Asia and that’s peace. I expected something better from the New Yorker. [Diaries, CW 8, 28]

I’d like to write an article on Everyman prudery sometime. Geoffrey of Monmouth; the translator’s smug sneer on p. 248. Malory, according to Blunden. The Gulliver’s Travels “For Young People” has been modified. The Pepys is the worst, of course, for B. [Braybrooke] has even been allowed to tamper with the family text to the extent of printing “prostitute” for “whore,” on the three-point landing principle: I remember the New Yorker’s account of a play, I think Sean O’Casey’s, where Lilian [Lillian] Russell was billed as a “Young Whore.” Several papers printed it as a “Young Harlot” (more cushion for sensitive moral fundaments in two syllables). One “blushed prettily and whispered ‘A Young Girl Who Has Gone Astray.’” One said “with Miss Russell and the following cast.” (ibid., 33)

I’d like to do a New Yorker type of story with echoes from a club like our S.C.R. [Senior Common Room]. Krating: “. . . you see it isn’t the Espinani Jews, the real Jews, that are the trouble; it’s the Polish kind that cause . . .” “. . . So when the inspectors arrived they found the coal all stacked up in the bathtub. You see, you can’t just . . .” (ibid., 42)

Hell, Christopher Isherwood in this New Yorker has swiped an idea I had years ago: married couple arguing with each other by diary [Christopher Isherwood, “Take It or Leave It,” New Yorker, 18 (24 October 1942): 17–19]. (ibid., 50)

Eleanor Coutts dropped in to say goodbye. She tells me of a good movie (British) about Palestine: “My Father’s House.” The New Yorker speaks of a French one on the Auschwitz camp, “La Derniere Etape.” I’m not satisfied with the day. Very little German, no music, little reading, no writing & a good deal of buggering around. A new New Yorker was part of the trouble: the rest was mainly lack of energy. (ibid., 60)

The New Yorker has an interesting article on embezzlement which points out that it’s not, after all, a crime against the people, but against an employer or employing corporation, so that it’s really a civil rather than a criminal matter [“Annals of Crime: The Wily Wilby, I and II,” New Yorker, 24 (1 January and 8 January 1949): 23–33, 34–45). The article is about a Canadian citizen, Ralph Marshall Wilby, who was caught for embezzlement in both Canada and the U.S.] (ibid., 72)

[Mr. Shabaeff] couldn’t stand Americans & came to Canada—his best friend in Montreal is Fritz Brandtner. He’s color-blind, which may account for the curious magenta lips on the Madonna & Child that make them look a bit like perfume ads in the New Yorker. . . . ([Mrs. Shabaeff] says Lismer said “Shabaeff is the greatest artist in Canada, but he’s a devil,” which I put among the New Yorker’s Remarks We Doubt ever Got Made Department, but perhaps she hypnotizes people into murmuring the right responses) (ibid., 182)

The New Yorker quotes Saroyan as saying that children are the only real aristocracy, which, believe it or not, really means something” [ The anonymous reviewer of William Saroyan’s The Assyrian and Other Stories quotes Saroyan as saying that children are “the only aristocracy of the human race” (The New Yorker 25 [1 January 1950]: 86)]. (ibid., 235)

Slept in a bit this morning, & when I got out I skipped the Forum office again. I don’t know why I should choose that to play hookey from—well yes I do. But I’ve got to stop this nonsense. I went & had a shoeshine & a haircut instead, & read the New Yorker. (ibid., 305)

I also saw contemporary American painting, which continues to bore me—more sentimental stereotypes. It’s all so photographic—not in technique but in conception. The same deliberately picturesque or obviously epigrammatic subjects, usually with a corny title attached, that one gets at photographic exhibitions. Like a series of New Yorker covers without detachment or humor. (ibid., 421)

More aimless gossip: the New Yorker going phut after Ross’s death, & the like. (ibid., 507)

The nine o’clock did half of Samson Agonistes, talking a bit about the nature of tragedy. I was tired & broke my consulting hours to go out for a New Yorker & a cup of coffee. (ibid., 601)

One of the things about Paradise Lost that startles and amuses students is the curiously domesticated life that Milton ascribes to Adam and Eve in Eden. They are suburbanites too relaxed to bother putting on clothes, preoccupied with their gardening and their own sexual relations, delighted when an angel from the neighbouring city of God drops in for a cold lunch, exchanging news of their own activities for news of what goes on in the big world, about which they are mildly but not excessively curious. The atmosphere is rather like a New Yorker cartoon of a nudist camp with a naked retired colonel sitting in a leather chair with a drink and a cigar and reading the Times. That strikes us as grotesque because we think of the original state of man as savage, emerging from an animal life by imperceptible stages. But Milton stands for that greater, older, wiser tradition which tells us that the original state of man was civilized, and that the suburbanite is closer to the core of human nature than the orang-utan is. (Northrop Frye on Education, CW 7, 182)

The styles employed by journalists and advertisers are highly conventionalized rhetorics, in fact practically trade jargons, and have to be learned as separate skills, without much direct reference to literature at all. A literary training is a considerable handicap in trying to understand, for example, the releases of public relations counsels. I am not saying this just to be ironic: I am stating a fact. I remember a New Yorker cartoon of a milkman who found the notice “no milk” on a doorstep, and woke up the householder at four in the morning to enquire whether he meant that he had no milk or that he wanted no milk. (ibid., 197)

I can seldom understand the statements about goals that departments of education set for the end of public school, for the end of high school, for the end of anything that seems to have a discernible end. They all sound like much the same set of goals, and the entire operation reminds me of the New Yorker cartoon of a man lying in bed and reading a book called How to Get Up and Get Dressed. There can really be no goal where taking the journey itself is the best thing to be done. (ibid., 541)

The other day the Women’s Lit. met, and as they’ve decided to invite men this year, Cragg and I went over and heard Leo Smith saw some Italian suites. Leo Smith is a good head, if he didn’t look so much like something out of the New Yorker. (Frye‑Kemp Correspondence, CW 1, 356)

Thank you for sending Barbara’s [Barbara Sturgis’s] letter on—I was planning to ask you for it in my next letter. I congratulate Barbara for having disinterred two authentically English jokes. But one swallow, or even two, won’t make a summer, and nothing so obvious as a joke would ever make The New Yorker. There’s one store in town that sells that magazine, thank God. The Aug. 15 one contains a swell parody of Huxley [Wolcott Gibbs, “Topless in Ilium,” New Yorker, 12 (15 August 1936), 25–6; the parody is of Huxley’s Eyeless in Gaza]. (Frye‑Kemp Correspondence, CW 2, 530)

I’ve talked to a lot of people but I haven’t said anything important. Charlie Chaplin is here now, but I didn’t go—I had the New Yorkers. (ibid., 633)

Oh, well, things might be worse—I don’t have to look at pictures of squalling babies on the front page of the Toronto Star, for example. And thanks very very much for the New Yorkers—they helped a lot at a critical time. At any other time I’d say they were worth their weight in gold. (ibid., 654)

I don’t know why I’m writing you again so soon, sweet, except that your letter came this morning and the New Yorkers. I expect sending those magazines is a bit of a nuisance, but please keep on: silly as it sounds, they mean quite a bit to me. You do do them up so well. (ibid., 679)

Your efficient tying‑up of New Yorkers reminds me of a remark of Stephen’s [Stephen Burnett’s] in a particularly sniffish mood—“Why are all Canadians so utterly hopeless at doing up parcels?” Edith [Burnett]: “Because we’re not a nation of shopkeepers.” (ibid. 680)

Thanks very, very much for the New Yorkers and your bulletins, both of which were funny in places. I’m damned if I’m going to start a new sheet to tell you I love you. (ibid., 703)

P.P.S. A New Yorker would help my state of mind. (ibid., 751)

I phoned Aunt Hatty and she came down just as I was about ready to start. One of her mistakes was going to the Bonaventure Station—there was a chapter of accidents I don’t remember—and she gave me some fruit and two magazines. She discussed magazines with me, saying the New Yorker was clever but awful, that Wilbert [Howard] read the Coronet, also clever but awful, but generally an English one called For Men Only. I said it was a dirty rag, which it is. She said the magazines were Coronets—or I thought she did—but one of them turned out to be a Men Only. I must write her and apologize. (ibid., 778)

Last Sunday night the J.C.R. [Junior Common Room] had a meeting and as usual voted down the New Yorker. I said I didn’t care because I got it anyway. (ibid., 810)

I’ve neglected you shamefully since I’ve come to Paris: part of the reason is about ten New Yorkers, which I got, and thanks. (ibid., 830)

I keep wondering if you get all my letters and postcards and things. I haven’t seen a sign of your picture yet, and can’t imagine what’s happened to it. I got the New Yorkers though, and thanks very much. (ibid., 851)

I’ve caught cold, but I’m getting over it, and the weather’s drying me out gradually. Thanks for the New Yorkers. The Forum didn’t send me the issue with my article in it, but they did send me the one with Newton’s article in, which I liked: I hadn’t realized he’d been in Canada. (ibid., 855-6)

Thanks for the New Yorkers: the cartoons are a bit feebler, but the stories have more variety: fewer reminiscences about eccentric Aunt Emmas. . . . By the way, if you send any more New Yorkers over, ask for the big stamps, will you? I’m besieged with collectors in Merton. (ibid., 890)

The New Yorker some time ago, reporting on a televised broadcast of the UN, spoke of the camera’s catching the flash of contempt on Malik’s face when a vote went against him. There was just at touch of apologetic awe in the account, as though the contempt had something in it impressive & convincing. But the contempt of the limited for the flexible mind is one of the ultimate demonic data of life, & it has nothing in it to be noted except its danger. (Northrop Frye’s Notebooks on the Bible, CW 13, 66)

There was a New Yorker cartoon of crowds of people marching under different banners or slogan boards representing different schools of psychotherapy. I remember one board labelled “Sons and Daughters of the Primal Scream”; others, which I’ve forgotten, were connected with transactional therapy, simultaneous orgasm cults, and so on. All these schools claim to be therapeutic and also to be based on scientific principles. (ibid., 309)

I had more interest in the poetry because it was a little better written than the prose, and we [at the Canadian Forum] didn’t have a great deal of room for the kind of short story the New Yorker runs, for instance, and during the 1930s and 1940s there were a great many didactic stories with a political moral. I found a lot of them very dull so I was more interested in the poetry because on the whole it was a more interesting genre. (Interviews, CW 24, 705-6)

A Restoration or Victorian judicial critic of Shakespeare, or a modern critic like the late Wolcott Gibbs of the New Yorker, will tend to judge Shakespeare by the qualities that would please him if they were exhibited by a contemporary. (“The Critical Path” and Other Writings on Critical Theory, CW 27, 123)

Those who followed in the New Yorker the record of Miss Marianne Moore’s struggles to make her poetic talents useful to the Ford Motor Company in its search for a name for its new car (it was finally called “Edsel”) will understand that the gap between the poet and society is one that the poet cannot do much to bridge. (ibid., 234)

We have a new type of periodical in the Tatler and Spectator of Addison and Steele, and later in Johnson’s Rambler, featuring a blend of light and serious tones rather like the contemporary New Yorker. (Northrop Frye on Literature and Society, CW 10, 304)

About sixty eerie drawings, with mysterious titles, of naked, gnomelike figures, ranging in treatment from allegory to surrealism. The best have a disturbingly haunting quality that one rarely finds in the more realistic captioned cartoons of the New Yorker school, and in fact are “funny” only to the extent of making one giggle hysterically. (Northrop Frye on Modern Culture, CW 11, 113)

Well, if an audience is ready to accept poetic & symbolic expression normal in drama it will get its dramatic poets. If it instinctively regards poetry & symbolism as a monstrously perverse way of expressing oneself it won’t. Anyone who has read a Walcott Gibbs account of a Shakespeare play in the New Yorker (he talks exactly as Rymer did in the 17th c.) should understand why we can’t produce a Shakespeare. And it wouldn’t do to turn to another critic, because Gibbs says what practically everyone in a modern audience really feels (if Shakespeare really held the stage through his stage craft instead of his reputation, a dozen of his contemporaries would hold it too). (Northrop Frye Notebooks on Renaissance Literature, CW 20, 114–15)

“Some of the tricks that have lasted longest & because fixed in the popular imagination must be the remnants of fertility rites. The word is an obvious symbol, & has its kinship with Aaron’s rod & the pope’s staff that puts forth leaves in ‘Tannhauser.’ Its production of rabbits & flowers from a hat has become the accepted type trick of conjuring. and the magician who escapes from the box: what is he but Adonis & Attis & all the rest of the corn gods that are buried & rise?”—Edmund Wilson in The New Yorker, Mar.11, 1944. (ibid., 149–50)

Helen Kemp

I was so glad to hear from you so soon, and sorry that you had a bad journey. If it had not been for the pile of New Yorkers you gave me I should have been very doleful indeed. But I applied myself to them very diligently. I had a letter from Barbara quoting two English jokes, beginning as she says, her anti‑New Yorker campaign right away! (Frye‑Kemp Correspondence, CW 2, 523)

I have been in bed all afternoon reading New Yorkers. (ibid., 541)

Mom went downtown to get her eyes examined but she’ll be back soon and I have been reading more New Yorkers. There was a story about Rose O’Neill who invented kewpie dolls—she does sound an ass. There were two articles about this new conductor of the Philharmonic, Janssen, who seems to have all the virtues dear to Alger fans [The articles Helen Kemp refers to are Alexander King, “Kewpie Doll,” New Yorker, 10 (24 November 1934), 22–6; Robert A. Simon, “Local Boy Makes Music,” New Yorker, 10 (24 November 1934), 38, 40; and Robert A. Simon, “On Seeing Janssen—Rachmaninoff Returns—A Quartet’s Finale,” New Yorker, 10 (17 November 1934), 79–81]. (ibid., 544)

I have thought of you so much this week, surrounded by ocean and nothing else. I do hope you weren’t sick. Harold sends his love. Will send some New Yorkers soon. (ibid., 558)

I sent you 2 bundles of New Yorkers last week [Frye was at Oxford]. (ibid., 618)

It is late, I must go to work now. I’ll send you some more New Yorkers to‑day. (ibid., 644)

I love you very very much, my dear, and I hope you get my little book before long. I will send you some more New Yorkers on Monday. (ibid., 662)

My dear: I sent some New Yorkers off a few days ago and the mutt in the Post Office gave me the wrong amount of postage so they were returned for more. However, you’ll get them, but a little later by a few days. (ibid., 690)

To‑night we had the Lescaze lecture, last night I was down for the university settlement evening, next Monday there is a lecture by Eric Newton and on Friday the Leo Smith musicale. And so it goes! Lescaze is simply grand—you get the idea from the article in The New Yorker {Dec 12} [Robert M. Coates, “Profiles: Modern,” New Yorker, 12 (12 December 1936), 28–38—an article on William Lescaze, a leading modernist architect] but to hear him talk and to see all the buildings he has designed—!

I have a whole stack of New Yorkers to send you soon. I’m sorry for the delay. (ibid., 733)

P.S. Am sending New Yorkers soon. (ibid., 821)

The next Forum is out and we ran Newton’s article—it arrived just in time. I probably told you that. I’ll send on the stories and more New Yorkers right away. (ibid., 850)