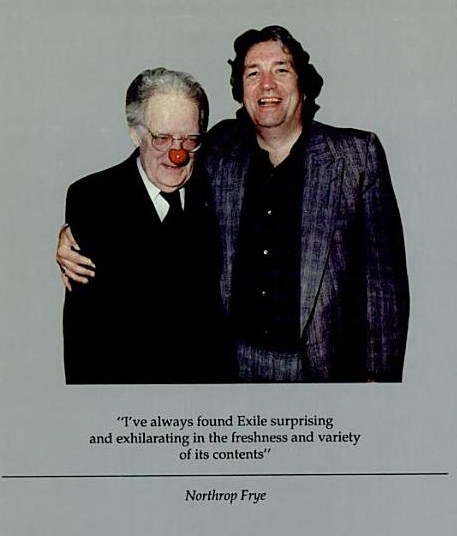

This is the elusive photo of Frye wearing a clown nose at a party for Morley Callaghan. That’s Morley’s son Barry Callaghan standing next to him. The photo (along with Frye’s blurb) appears on the back cover of Barry’s Fifteen Years in Exile, his memoir about his years at the Exile Quarterly. The very pleasant circumstances in which the photo was taken are described in this post from last year.

Daily Archives: December 6, 2010

“Remembering Northrop Frye: Recollections by His Students and Others”

Regarding the earlier post about a collection of letters called Remembering Northrop Frye: Recollections by His Students and Others in the 1940s and 1950s:

The context for Remembering Northrop Frye is Frye’s diaries, which he kept intermittently from 1942 until 1955. Altogether there are seven diaries, or at least seven different books in which he recorded his daily activities, typically at the end of each day. In the early 1990s I began transcribing the diaries, which form a substantial body of writing––more than a quarter million words altogether. They were published as The Diaries of Northrop Frye (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001. Collected Works of Northrop Frye, vol. 8). In the course of this project I sought to identify the more than 1,200 people who are mentioned by Frye. I corresponded with a number of them, most of whom were his students at Victoria College in the 1940s and 1950s. To take one year as an example, I wrote to seventy‑eight people who made an appearance in the 1949 diary: fifty‑nine responded. I would ordinarily inquire of all those I wrote whether they remembered the occasion mentioned by Frye, and I would usually invite them to provide some biographical information about themselves and to share their memories of Frye as a person and teacher. I often requested the correspondents to help identify others mentioned in the diaries. I was interested in learning specific details in order to annotate the diaries, but my invitation to the correspondents to reflect on their experiences with Frye and on the Victoria College scene at the time would help me, I hoped, to reconstruct the social landscape on campus during the seven years covered in the diaries. I received two unsolicited letters, sent to me at the urging of other correspondents. All were generous in their responses. Altogether the replies I received, many quite extensive, provide a rather remarkable body of reminiscence, and that is what is the reproduced in the eighty‑nine letters in Remembering Northrop Frye, scheduled to be released by McFarland and Co. early in 2011.

One motif that runs throughout is the power and generous presence that Frye had as a teacher. Here is a sampler of the correspondents’ tributes:

• Northrop Frye was the greatest single influence in my life. His view of things permanently altered the shape, not only of literature, but of life as I saw it. And even now, though inevitably modified––& I fear sometimes distorted––Norrie’s view of literature and the world still shapes my own. (Phyllis Thompson)

• My own memories of Frye are filled with respect and gratitude. What incredible luck to have been “brought up” by him! I remember the excitement of his first lecture every fall. There was a ping of the mind, like a finger snapped against cut glass. You came back from your grungy summer job and then there it was, the whole intellectual world snapped into life again, the current flowing. (Eleanor Morgan)

• I still cannot believe my good fortune in having been taught so many stimulating courses by a person of such brilliance and compassion. His ideas were electrifying, encyclopedic, and revolutionary. . . . Each year when I returned to the university, the hinges of my mind sprang open, and my brain pulsed with the excitement of Frye’s thinking, his eloquence, and his wit. But what keeps his influence on my life vivid and profound to this day is that he enabled us to translate the leaps of intellect we experienced in his lectures into the emotional underpinnings of a way to look at the world and one’s place in it––in short, to be in the world, yet not of it. (Beth Lerbinger)

• Frye would lecture without notes, yet the class rarely turned haphazard. He asked questions constantly that required a knowledge not only of the Bible and classical mythology, but also of the major works in English and American literature. No one could keep pace with all the references, but still the effect was to illuminate and give a structure to a rich and fascinating verbal universe. And then, as an added bonus, just when you thought he had reached the conclusion his investigation was leading to, he would use that “conclusion” as the opening position in a new line of investigation. (Ed Kleiman)

• In short, the Frye course [Religious Knowledge] in one way made for a lot of fun at home. In another way it changed our lives forever. (M.L. Knight)

• In 1950 while at library school there was no need for me to run hard at either studying or football so I and a classmate would range the campus auditing lectures and we found Frye had the largest, most intent crowds and the most graduate students. Even now I take up my lecture notes, particularly on Job and Carlyle and Matthew Arnold, and find him stimulating. (Douglas Fisher)

• The outstanding lecturer, the one who made my university education a spiritual one, setting the mode for the rest of my life, was Northrop Frye. . . . My memories of Northrop Frye are fond and precious. I still have the essays I wrote for him, with his comments on them. I have a collection of almost all of his published books. . . . I wrote to him a few times. I recall that one letter, probably the one that occasioned his notation in his diary, was to thank him for what he had taught to me, because of the perspectives he gave me about life. (Jodine Boos)

• His shyness and genuine modesty, coupled with a witty self-deprecation, made him the quintessential Canadian. Underneath all that, of course, was the finest literary mind in the Western world. (Don Harron)

• I really did not know Norrie as a teacher. I was never in one of his classes, but in our interviews he taught me much & indeed he knocked a lot of fuzziness out of my head. He could not make me into a scholar, but he did encourage me as a poet; I owe him a great deal, & I always felt friendly towards him. (George Johnston)

• I was in Philosophy & English and we had marvellous, thrilling courses with Frye on the Elizabethan period, Spenser & Milton, 19th Century Thought, The English Bible . . . They filled my thoughts for three years! Frye was university for me. Nothing else counted. I couldn’t just take notes on his lectures, I had to try to write down every single word he said. . . . I got so spoiled listening to Frye that I couldn’t stand other lecturers. (Gloria Vizinczey)

• I expect a lot of people, when they heard he had died, said to themselves, “I may as well lay down my pen since there is no one in the world for whom I can now write, no one whose good assessment I crave.” (Catharine Hay)

Osbert Sitwell

Osbert with his sister Edith

Today is Osbert Sitwell‘s birthday (1892-1969). Sitwell’s sister, Edith, provided a warm review of Fearful Symmetry in the Spectator (10 October 1947).

Here’s Frye’s diary entry for January 4, 1949:

Lunch with Osbert Sitwell at the University Club–Lionel Massey gave the party, & Doug LePan & Paul Arthur & a man I didn’t know were there. Sitwell was a high-coloured solid-looking aristocrat with iron-grey hair, who until he opened his mouth could have been either a cultivated man or a barbarian. Wonderful lunch–oysters & a fine dry red Portuguese wine. The conversation was commonplaces, though highly cultivated commonplaces. He is deeply impressed by my book–says he’s recommended it to a lot of people including the painter John Piper. Edith [Sitwell] is at the St. Regis on East 50th St, New York. He’s Jung’s sensation type, not a thinker primarily. (CW 8, 62)