This is a delayed response, Russell, to your post on Frye and “The Return of Religion.” I was piqued by some of your suggested criticisms of Frye’s approach to the Bible, and so resolved to undertake some of the reading you suggested. Eagleton? Well, nah, I think I’ll give that a pass, at least for the moment. But I did take a deep breath and plunged into Robert Alter’s article on Frye and the Bible in Frye and the Word.

It might be useful, but much too laborious and really not worth the time and energy to go through all the ways the man distorts Frye’s argumentation in order to make him look foolish, uninformed, and deluded. He condescendingly alludes to Frye’s shakiness on the ground of Biblical criticism and theology, his philological ignorance, his Christianizing of the Bible, etc. But if you compare the examples he adduces to make his case you will find that the only way he can undermine Frye is by attacking a dummy custom-made for the purpose.

To avoid tedium, I will contain myself to one example. He claims that in The Great Code Frye, in a discussion of Ecclesiastes, translates the hebrew word “hevel” as “dense fog.” In sneering reproof, Alter observes that the word means mist or vapor, not dense fog. However, if you look at the pertinent passages in The Great Code you will discover that Frye mentions the significance of the word “hevel” and notes that it “has a metaphorical kernel of fog, mist, or vapor,” and “acquires a derived sense of ‘emptiness’.” It is only a good page later that, in a discussion of the invisible world as the means by which we see the visible one, he uses the phrase “dense fog”: “if we could see air we could see nothing else, and would be living in the dense fog that is one of the roots of the word ‘vanity.’”

This is not even splitting hairs; it’s splitting nothing, since there is nothing Alter can really argue with. That “vanity” is like the “void’ of Buddhist thought“, as Frye points out in the same discussion, is exactly what Alter himself says: that the significance of the word “hevel” is the vaporousness, the insubstantiality of what we take to be reality, or its “nothingness,” as Frye says. So a disagreement must be invented where there isn’t one. He accuses Frye of tweaking the Hebrew, but who is really doing the tweaking of someone’s words here?

Alter fails to mention any of this. This is what I referred to in a previous post as intellectual dishonesty. Like other critics of Frye, such as Said–and predictably, like Said, Alter dismissively praises Frye for his “ingeniousness”–Alter engages in a deliberate short-circuiting of Frye’s arguments in order to caricature and distort them into something that at least sounds foolish, uninformed, and deluded, because at some level I suspect they know they aren’t. It would not be hard to show how egregiously Alter follows this procedure throughout his essay.

The bottom line is: Alter simply wants nothing to do with the imaginative element, with metaphor or myth in the Bible, or if it must be admitted, since it is everywhere, only as a kind of rhetorical ornamentation that is easily hedged in by a crabbed and mean-spirited descriptivism.

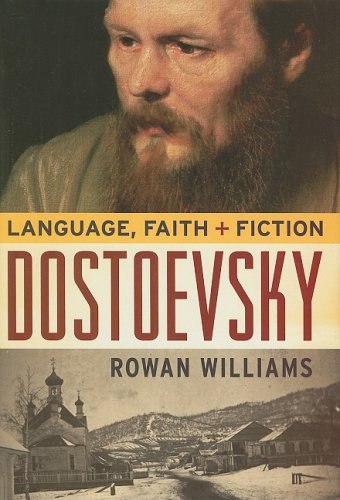

So what a joy it was today when I received my copy of Rowan Williams’s Dostoevsky, Faith and Fiction (just in time for my class on Dostoevsky next week), and read the following passages in the first three pages of his preface. You’d think he’d read Frye, and I guess he may well have at some point, or read someone who read him:

Metaphor is omnipresent, certainly in scientific discourse (selfish genes, computer modelings of brain processes, not to mention the magnificent extravagances of theoretical physics), and its omnipresence ought to warn us against the fiction that there is a language that is untainted and obvious for any discipline. We are bound to use words that have histories and associations; to see things in terms of than their immediate appearance means that we are constantly using a language we do not fully control to respond to an environment in which things demand that we see more in them than any one set of perceptions can catch.

The most would-be reductive account of reality still reaches for metaphor, still depends on words that have been learned and that have been used elsewhere . . .

This will involve the discipline of following through exactly what it is that language of a particular religious tradition allows its believers to see–that is, what its imaginative resources are.

This is not–pace any number of journalistic commentators–a matter of the imperatives supposedly derived from their religion. It is about what they see things and persons in terms of, what the metaphors are that propose further dimensions to the world they inhabit in common with nonbelievers.

Williams speaks of the “forming of a corporate imagination” as “the more or less daily business of religious believers,” of “a common imagination at work . . . in the labors of a variety of creative minds.” He explains that the series for which the Dostoevsky book was written “look[s] at creative minds that have a good claim to represent some of the most decisive and innovative cultural currents of the history of the West (and not only the West), in order to track the ways in which a distinctively Christian imagination makes possible their imaginative achievement.”

And he asks:

What, finally, would a human world be like if it convinced itself that it had shaken off the legacy of the Christian imagination?

He speaks very insistently, not of the imperatives of belief, but of metaphor and imagination.

What a godsend for a church to have such an archbishop.