This is a delayed response, Russell, to your post on Frye and “The Return of Religion.” I was piqued by some of your suggested criticisms of Frye’s approach to the Bible, and so resolved to undertake some of the reading you suggested. Eagleton? Well, nah, I think I’ll give that a pass, at least for the moment. But I did take a deep breath and plunged into Robert Alter’s article on Frye and the Bible in Frye and the Word.

It might be useful, but much too laborious and really not worth the time and energy to go through all the ways the man distorts Frye’s argumentation in order to make him look foolish, uninformed, and deluded. He condescendingly alludes to Frye’s shakiness on the ground of Biblical criticism and theology, his philological ignorance, his Christianizing of the Bible, etc. But if you compare the examples he adduces to make his case you will find that the only way he can undermine Frye is by attacking a dummy custom-made for the purpose.

To avoid tedium, I will contain myself to one example. He claims that in The Great Code Frye, in a discussion of Ecclesiastes, translates the hebrew word “hevel” as “dense fog.” In sneering reproof, Alter observes that the word means mist or vapor, not dense fog. However, if you look at the pertinent passages in The Great Code you will discover that Frye mentions the significance of the word “hevel” and notes that it “has a metaphorical kernel of fog, mist, or vapor,” and “acquires a derived sense of ‘emptiness’.” It is only a good page later that, in a discussion of the invisible world as the means by which we see the visible one, he uses the phrase “dense fog”: “if we could see air we could see nothing else, and would be living in the dense fog that is one of the roots of the word ‘vanity.’”

This is not even splitting hairs; it’s splitting nothing, since there is nothing Alter can really argue with. That “vanity” is like the “void’ of Buddhist thought“, as Frye points out in the same discussion, is exactly what Alter himself says: that the significance of the word “hevel” is the vaporousness, the insubstantiality of what we take to be reality, or its “nothingness,” as Frye says. So a disagreement must be invented where there isn’t one. He accuses Frye of tweaking the Hebrew, but who is really doing the tweaking of someone’s words here?

Alter fails to mention any of this. This is what I referred to in a previous post as intellectual dishonesty. Like other critics of Frye, such as Said–and predictably, like Said, Alter dismissively praises Frye for his “ingeniousness”–Alter engages in a deliberate short-circuiting of Frye’s arguments in order to caricature and distort them into something that at least sounds foolish, uninformed, and deluded, because at some level I suspect they know they aren’t. It would not be hard to show how egregiously Alter follows this procedure throughout his essay.

The bottom line is: Alter simply wants nothing to do with the imaginative element, with metaphor or myth in the Bible, or if it must be admitted, since it is everywhere, only as a kind of rhetorical ornamentation that is easily hedged in by a crabbed and mean-spirited descriptivism.

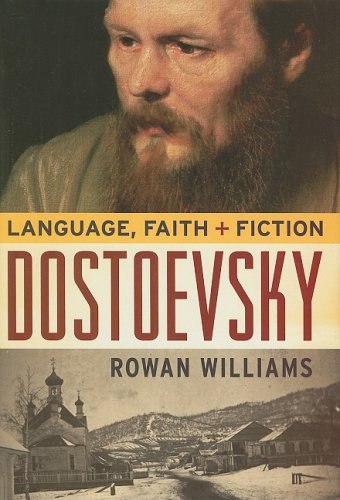

So what a joy it was today when I received my copy of Rowan Williams’s Dostoevsky, Faith and Fiction (just in time for my class on Dostoevsky next week), and read the following passages in the first three pages of his preface. You’d think he’d read Frye, and I guess he may well have at some point, or read someone who read him:

Metaphor is omnipresent, certainly in scientific discourse (selfish genes, computer modelings of brain processes, not to mention the magnificent extravagances of theoretical physics), and its omnipresence ought to warn us against the fiction that there is a language that is untainted and obvious for any discipline. We are bound to use words that have histories and associations; to see things in terms of than their immediate appearance means that we are constantly using a language we do not fully control to respond to an environment in which things demand that we see more in them than any one set of perceptions can catch.

The most would-be reductive account of reality still reaches for metaphor, still depends on words that have been learned and that have been used elsewhere . . .

This will involve the discipline of following through exactly what it is that language of a particular religious tradition allows its believers to see–that is, what its imaginative resources are.

This is not–pace any number of journalistic commentators–a matter of the imperatives supposedly derived from their religion. It is about what they see things and persons in terms of, what the metaphors are that propose further dimensions to the world they inhabit in common with nonbelievers.

Williams speaks of the “forming of a corporate imagination” as “the more or less daily business of religious believers,” of “a common imagination at work . . . in the labors of a variety of creative minds.” He explains that the series for which the Dostoevsky book was written “look[s] at creative minds that have a good claim to represent some of the most decisive and innovative cultural currents of the history of the West (and not only the West), in order to track the ways in which a distinctively Christian imagination makes possible their imaginative achievement.”

And he asks:

What, finally, would a human world be like if it convinced itself that it had shaken off the legacy of the Christian imagination?

He speaks very insistently, not of the imperatives of belief, but of metaphor and imagination.

What a godsend for a church to have such an archbishop.

I have no doubt that Rowan Williams is one of the smartest people on the planet and a prayerful and spiritual man. And yet he is a homophobe. He chooses the unity of the Anglican communion over the blessing of same-sex couples, secondary concerns over primary concerns. He has a very sophisticated and compelling theory of the body of Christ that justifies all this. I’m not saying that he is obviously wrong. He is smarter than I am. But to accept the whole of what Rowan Williams says is to deny Frye the primacy of primary concern.

Rowan Williams reminds me of Frye when he says the the crucifixion of Christ is not only something that “bad” people are responsible for, but is the considered conclusion that we all come to because it is expedient for one man to die for the people. Of course he turns this around and says that it is schism, and not the destruction of human beings that is the real analogy to the crucifixion of Christ. Two kinds of Christians. It is expedient that gays should be executed in Uganda as long as the church remains unbroken.

I certainly don’t accept the whole of what he says, if that is his position concerning gays, Clayton. I certainly liked what he had to say in his preface to his Dostoevsky book. I thought it was quite impressive, and therefore I am looking forward to reading the book further. Having checked his bio out on wikipedia I can also see that he has more than just that position I don’t necessarily agree with.

What you have to say reminds me, as a student of American literature, of the increasingly untenable and morally disgusting compromises on the issue of slavery that were made by the Northern States with the slave power in the South in order to avoid “schism.” Any compromise was seen as preferable to the sundering of the Union, and it was all to no avail in the end anyway. The Union had to be broken.

I’m not being sarcastic when I praise his intelligence or piety. There is much to learn from him. I very much liked his little book, _Where God Happens_ and his Holy Week lectures on prayer which are available as mp3 files on his website. But he’s the kind of person who would urge respectful dialogue between the devil and the people in hell.

It worries me, Joe, but I think that’s one of the better analogies of the position of the Anglican Communion that I’ve encountered–and worse, I find it accurately captures my own anxiety for the Communion’s future.

While this blog focuses its gaze upon Frye and his work, the Anglican Communion and the issues Clayton mentions offer a parallel to some of the conversations we’ve had, particularly around the line of criticism Joe condemns in his post. One of the reasons for the lack of condemnation of the current attack on homosexuals in Uganda seems to me to stem from a facile use of post-colonial thought: because of past bad acts, many areas and leaders of the Church fail to speak out against what is and should be condemned.

Thanks for sharing those bits of ++Rowan’s new book, Joe; my copy is sitting on a shelf, waiting for me to scratch out some time for it. I should bump it up on my to-read list.

Matthew, as you know, it’s not just post-colonial thought but also thought about homosexuality that ties the hands of the Anglican hierarchy. Homosexual relationships are incompatible with scripture according to the official doctrine of the Anglican Communion. Rowan Williams himself reiterates this on occasion, not so much to agree with it, but to make the point that it is the progressives and not the conservatives who are moving away from the church. (I for one think that what Rowan Williams believes in his heart of hearts is of no interest–either to me, to gays in general, or to God. His actions are what matter. I remember about 8 years ago when some gays were insisting that George W. Bush was not personally a homophobe.)

When you are yourself committed to a lie, you cannot speak truth to the power that is using that lie to do evil. That is the position Rowan Williams is in.

Yes, that is exactly how Frye sees it: belief has nothing to do with what you say you believe, but what your actions reveal you believe.

Further on Joe’s point about Robert Alter:

Another cheap shot by Alter is his critique of Frye’s interpretation of Leviathan in Jonah and Job. Alter picks up a phrase here and there from Frye’s Great Code discussion, but he’s not in the least fair to Frye’s extended account of the way this image functions across the biblical narrative. One of the advantages of looking at the Bible as a unity is that it permits Frye to link the images of the Leviathan as they appear in Psalms 74 and 104, Isaiah 27 and elsewhere (the word occurs six times in the Old Testament). Alter says that the “Leviathan is in no way a force contending with God.” But it is clearly such a chaotic force in Psalm 74, where God is said to have crushed the heads of this marine creature, and in Isaiah 27, we’re told that the lord will punish the fleeing, twisting serpent and will kill the sea dragon. The image was a familiar one in Hebrew culture, as it was in Ugaritic poems. Alter, who has no sense of what a mythical symbol is, wants to make Leviathan into a literal crocodile rather than a symbolic primeval monster, a creature quite like the Behemoth of Job 40, also a symbol of chaos and evil. Alter says that the author of the Book of Job “never so much alludes to the belly of the beast.” True, the Hebrew poet doesn’t allude to the belly; he refers to it directly: “Look at Behemoth . . . its power in the muscles of its belly” (Job 40:15, 16). One would think that the literal minded Alter would at least pay attention to the letter. What we can say for Frye’s reading of the sea monsters––and their link with Rahab––is that he’s got biblical scholarship, which sees the sea monsters as symbolizing chaos and evil, on his side.

Yes, and Alter, in the same essay, refers to the Leviathan myth–I don’t have my book handy so can’t quote the entire sentence–as being “caged” in Job, Isaiah, and the Psalms, as if these were minor books of the Bible and the imagery was in some kind of quarantine from the rest of the biblical story.

Alter also dismisses out of hand Frye’s reading of the earth=mother/bride imagery in the second creation myth: again, as Bob puts it, Frye has got biblical (and other) scholarship on his side, at least in the way in which creation myths are versions, displacements, adaptations of competing mythologies, such as the agricultural myth of a symbolically female reproductive Nature.

It is true that one has to learn how to think archetypally as a critic, and one can simply refuse to learn, but that is to simply ignore the imaginative element in the act of reading any story or poem, and this critical position can easily take advantage of the fact that the imaginative element in reading literature takes place mostly on an unconscious level, precisely because it is a compressed skill we learn from childhood on.

Alter is an excellent example of a militantly centrifugal critic, a normative realist or descriptivist. He puts all his intellectual energy into directing the verbal traffic of the Bible and literature outside, a critical cop breaking up any gathering of images. OK, move along now, disperse. The ideological underpinnings are worth noting: there is nothing but an objective dimension to reality, this is the way things are: obey and work.

Joe, Recently I read Terry Eagleton’s _Holy Terror_. It is an eloquent and thoughtful book: have a look sometime! Glad you liked Williams on Dostoevsky, at least on first impression. When I get a chance, I’ll post something on Alter, but I need to have another look at his essay myself.

Thanks, Russell. I will take a look at Eagleton’s book, on your recommendation. It is always good to put one’s prejudices on trial.

I will also go and take another look at Alter’s book on Stendhal and his biblical criticism. I hate to think I am doing the same caricaturing that I may be too glibly condemning in others.

A further note about Rowan Williams and the gay issue.

There are a class of people who discuss theological issues including homosexuality at a very high level. These are people of liberal and conservative and moderate persuasions, but they have enough in common that they can speak to each other at conferences, in academic institutions, and on the internet ad infinitem. Rowan Williams is their high priest. These are generally people who hate the brutishness of popular homophobia, but nor do they accept the popular progressive call to immediate change. They are plagued by a tentativeness that sends them back into discussion, back to scripture, back into theological studies of all kinds. The prose they produce is elegant, reasoned, intelligent, clear. Their expressions of concern for gay people and for the various sides of the debate are clearly sincerely felt. To them, the gay issue is an issue affecting real flesh and blood people, and they make a point of never forgetting that, and yet they also know that sincerity is in bed with self-deception, and so there are no easy answers and the discussion must continue, and no one should do anything disrespectful of anyone else, most certainly should not cast the issue in black and white terms or generally be loud, brash, or make a nuisance of themselves. They are the height of the intellectual world. They have every spiritual and cultural attainment except truth and obedience.

What I love so much about Frye is that he also operates at the very highest intellectual level (and spiritual level), and yet he has a conscience and guts and is not afraid to cut through all the cowardly, sissified, hand-wringing bullshit that happens there:

“The one adversarial situation that does not impoverish both sides is the conflict between the demands of primary human welfare on the one hand and a paranoid clinging to arbitrary power on the other. Naturally, this black-and-white situation is often very hard to find in the complexities of revolutions and power struggles, but it is there, and nothing in any revolutionary situation is of any importance except preserving it.”

Yes, Clayton, that is a great quotation from Frye, and you articulate the issue so eloquently. I think, again, of the situation in antebellum America during the height of the abolitionist movement, and of the relentless compromising that led to the passing of the Fugitive Slave Law, a grotesque law that made it illegal, with severe consequences, to protect or harbor fugitive slaves in the North. All this to preserve the Union, a Union by this point completely corrupted by the pacts with the devil made to preserve it.

Even before that law was passed, another great visionary, Henry David Thoreau, wrote this, from Civil Disobedience or Resistance to Civil Government, which I thought of when I read the words you quote from Frye. It accords so beautifully with what you say about the expediency of crucifying Christ, in which society as a whole is complicit:

“How can a man be satisfied to entertain an opinion merely, and enjoy it? Is there any enjoyment in it, if his opinion is that he is aggrieved? If you are cheated out of a single dollar by your neighbor, you do not rest satisfied with knowing that you are cheated, or with saying that you are cheated, or even with petitioning him to pay you your due; but you take effectual steps at once to obtain the full amount, and see that you are never cheated again. Action from principle — the perception and the performance of right — changes things and relations; it is essentially revolutionary, and does not consist wholly with anything which was. It not only divides states and churches, it divides families; ay, it divides the individual, separating the diabolical in him from the divine.

Unjust laws exist; shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once? Men generally, under such a government as this, think that they ought to wait until they have persuaded the majority to alter them. They think that, if they should resist, the remedy would be worse than the evil. But it is the fault of the government itself that the remedy is worse than the evil. It makes it worse. Why is it not more apt to anticipate and provide for reform? Why does it not cherish its wise minority? Why does it cry and resist before it is hurt? Why does it not encourage its citizens to be on the alert to point out its faults, and do better than it would have them? Why does it always crucify Christ, and excommunicate Copernicus and Luther, and pronounce Washington and Franklin rebels?”

And here is another passage from the same essay:

“Paley, a common authority with many on moral questions, in his chapter on the ‘Duty of Submission to Civil Government,’ resolves all civil obligation into expediency; and he proceeds to say that ‘so long as the interest of the whole society requires it, that is, so long as the established government cannot be resisted or changed without public inconveniency, it is the will of God that the established government be obeyed, and no longer’ — ‘This principle being admitted, the justice of every particular case of resistance is reduced to a computation of the quantity of the danger and grievance on the one side, and of the probability and expense of redressing it on the other.’ Of this, he says, every man shall judge for himself. But Paley appears never to have contemplated those cases to which the rule of expediency does not apply, in which a people, as well as an individual, must do justice, cost what it may. If I have unjustly wrested a plank from a drowning man, I must restore it to him though I drown myself.This, according to Paley, would be inconvenient. But he that would save his life, in such a case, shall lose it. This people must cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people.”

There is another great passage from Thoreau, another attack on moral and political compromise, from “Slavery in Massachusetts.” This one, with its turning to the beauty of Nature in contrast with the ugliness of such human-all-too-human-compromise, brings to mind one of the paragraphs Bob quoted in his post on Frye and The Funny: “A sense of humor, like a sense of beauty, is a part of reality, and belongs to the cosmetic cosmos: its context is neither subjective nor objective, because it’s communicable. (Late Notebooks, 1:227).”

At the end of the Garden chapter in Words with Power, Frye writes: “The progress of criticism has a good deal to do with recognizing beauty in a greater and greater variety of phenomena and situations and works of art. The ugly, in proportion, tends to become whatever violates primary concern.”

Hence Thoreau’s recourse to the aesthetics and beauty of nature, against which, in proportion, the violation of primary concern that is the morally disgusting reality of slavery appears all the more ugly and loathsome. Thoreau was prophetically adept at this apocalyptic seizing of the “black-and-white situation [that] is often very hard to find in the complexities of revolutions and power struggles.” The reference to the “Nymphoea Douglasii” is an allusion to Stephen Douglas, the architect of the Fugitive Slave Act, later defeated by Lincoln in the presidential election. If there is an analogy to the Anglican Church’s position on homosexuality, Rowan Williams is perhaps–you would certainly have a better idea, Clayton, than I do– in the position much more of a Lincoln than a Douglas, in his temporizing strategy, if that is what his strategy is. Thoreau, I assume, would have as much contempt for Lincoln as he had for Douglas. Here is the passage from Thoreau, the closing passage of the speech:

“I walk toward one of our ponds; but what signifies the beauty of nature when men are base? We walk to lakes to see our serenity reflected in them; when we are not serene, we go not to them. Who can be serene in a country where both the rulers and the ruled are without principle? The remembrance of my country spoils my walk. My thoughts are murder to the State, and involuntarily go plotting against her.

But it chanced the other day that I scented a white water-lily, and a season I had waited for had arrived. It is the emblem of purity. It bursts up so pure and fair to the eye, and so sweet to the scent, as if to show us what purity and sweetness reside in, and can be extracted from, the slime and muck of earth. I think I have plucked the first one that has opened for a mile. What confirmation of our hopes is in the fragrance of this flower! I shall not so soon despair of the world for it, notwithstanding slavery, and the cowardice and want of principle of Northern men. It suggests what kind of laws have prevailed longest and widest, and still prevail, and that the time may come when man’s deeds will smell as sweet. Such is the odor which the plant emits. If Nature can compound this fragrance still annually, I shall believe her still young and full of vigor, her integrity and genius unimpaired, and that there is virtue even in man, too, who is fitted to perceive and love it. It reminds me that Nature has been partner to no Missouri Compromise. I scent no compromise in the fragrance of the water-lily. It is not a Nymphoea Douglasii. In it, the sweet, and pure, and innocent are wholly sundered from the obscene and baleful. I do not scent in this the time-serving irresolution of a Massachusetts Governor, nor of a Boston Mayor. So behave that the odor of your actions may enhance the general sweetness of the atmosphere, that when we behold or scent a flower, we may not be reminded how inconsistent your deeds are with it; for all odor is but one form of advertisement of a moral quality, and if fair actions had not been performed, the lily would not smell sweet. The foul slime stands for the sloth and vice of man, the decay of humanity; the fragrant flower that springs from it, for the purity and courage which are immortal.”

Thoreau, being a true prophet, wasn’t in the habit of mincing his words, and he was seriously pissed when he wrote this speech, a response to the controversial arrest and “rendition” by the state of Massachusetts of a fugitive, Anthony Burns, to his oppressor in the South, which brought the military to Boston to shut down the abolitionists who had stormed the federal courthouse to free him.

Here are the closing lines:

“Slavery and servility have produced no sweet-scented flower annually, to charm the senses of men, for they have no real life: they are merely a decaying and a death, offensive to all healthy nostrils. We do not complain that they live, but that they do not get buried. Let the living bury them: even they are good for manure.”