A reader’s response to a Frank Rich editorial, “The Rage Is Not about Health Care,” in the New York Times cites Frye on the hero:

The fact that the McConnells, Boehners, Cantors, and even McCains fear the wrath of unhinged, racist, screaming Teabaggers is the clearest indication possible that none of them are leaders. They are sheep. Abject figures who might be pitied for their impotence if they were not positioned to affect the direction of this country so negatively.

Literary critic Northrop Frye described the true leader as a hero, one who stands apart from the crowd, whose power stems from being able to adopt a position from strength rather than from weakness. Does this description call to mind anyone from the Republican party?

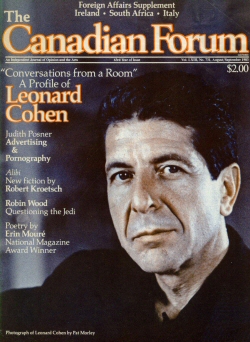

Historian and philosopher Isaiah Berlin, in his essay “From Hope and Fear Set Free” outlines the features that distinguish a rational person from an unfree, fearful person. Berlin states that the rational man is one who can act freely, not mechanically, who acts upon sound motives. The fearful man “is like someone who is drugged or hypnotised.”

Do the current crop of Republican “heroes” sound like either of these archetypes? Of course, it’s the second. They who foment fear are themselves fearful. They who are bound by ideological chains are barely able to see clearly. They who stand, not apart from the mob, in a position of strength, but hiding from it, in a fetal position of fear, cannot lead. They can only cower and whine and threaten.

There are no leaders on the right. They are led to the brink, like Lord Franklin’s doomed expedition, by addled fanatics like Limbaugh and Beck, and inanities like Palin; dragging down everyone with them, insisting that their weakness of mental acuity be recognized as some kind of sign that they are not “intellectuals” or socialists.

This country needs the balance of at least two functioning parties, both of which have leaders ready to stand up for the best America has to offer and to point her in the right direction. Unfortunately, we have only one rational party.

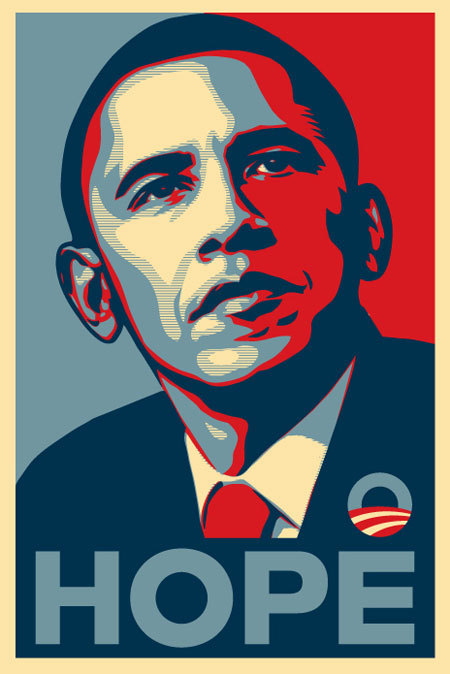

And if the above descriptions don’t fit any Republicans, they do seem to fit at least one Democrat.

That gentleman in the Oval Office.