httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zAuSEdPbqmo

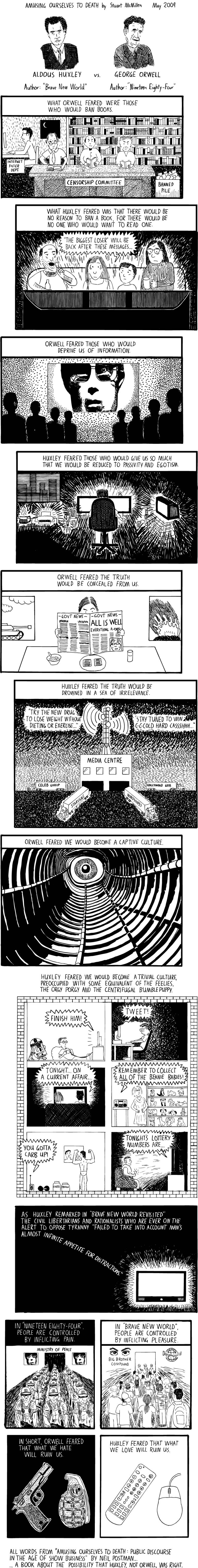

It’s been an especially good week for the super-rich. They’ve seen record corporate profits while Republicans continue to lobby tirelessly to prevent the Bush tax cuts from expiring for the top percentile of earners. And all the while these happy few have been on the receiving end of hundreds of billions of bailout dollars to sustain the financial market they collapsed two years ago by way of a greed so rapacious that the market did not (as all true believers believe it must) “self-correct.” There’s also the trillions of dollars worth of “quantitative easing” now working its way through the system in a last ditch effort to keep the whole crazy scheme ricketing along like the Rube Goldberg contraption it really is. As economist Nouriel Roubini and others have noted, we now have socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor.

The consequence is that tens of millions of people are chronically unemployed, stripped both of income and their remaining wealth: Ireland, Greece, and maybe Portugal are poised to go under, and perhaps take the rest of the world’s economy with them.

Don’t worry about the super-rich, however. In the U.S. alone, prior to the 2008 crash, they owned about 34% of the nation’s wealth; they now own about 38%. And while many millions of people must do without any income at all, the top 1% take in 25% of it. One assumes that they are doing so while curing cancer, resolving the suicidal impulses that drive global warming, and selflessly developing a free-of-charge vaccine for avian flu.

Tonight we’re running a restored version of Fritz Lang’s 1927 masterpiece Metropolis. Poetry, Auden says, changes nothing. And yet it still might serve as a reminder just how much everything can change because it ought to be changed.

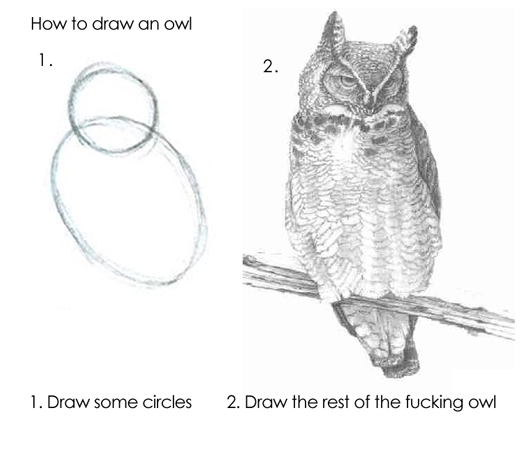

Here’s Frye in conversation with David Cayley on being a “bourgeois liberal”:

Cayley: You’ve described yourself as a bourgeois liberal and even said that people who aren’t bourgeois liberals are still “in the trees.”

Frye: Or would be if they could.

Cayley: I don’t quite understand what you mean by that. This seems on the face of it a strange statement for a social democrat and a Methodist and a populist to make.

Frye: Well, the bourgeois liberal to me is the nearest analogy I can think of to a man who is sufficiently left alone by the structure of authority in his society to develop his individuality. Because he’s a liberal, he doesn’t become an anarchist, that is, he doesn’t grab all the money and corner all the property in sight. He’s a person who can relate to other people. He doesn’t withdraw from society or become a mass man.

Cayley: So the emphasis is not the same as Marx gives the term “bourgeoisie” when he uses it to signify the hegemony of a certain class?

Frye: The bourgeois liberal is capable of seeing himself as having a certain position in society. He’s also capable of seeing something that that situation puts him into. You can’t avoid being conditioned, but you can to some extent become aware of your conditioning. (CW 24, 971)

The rest of the movie after the jump.

Continue reading →